Review by Frank Plowright

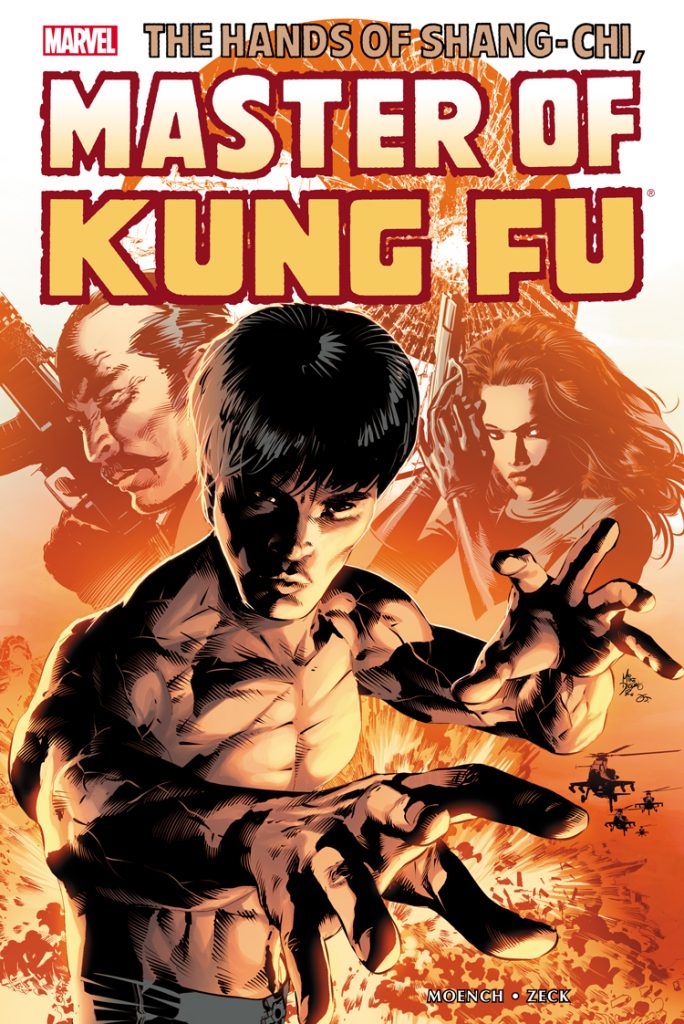

Master of Kung-Fu seemed to have lost its way by 1978, its trajectory a flame that burned brightly and briefly before dropping back to a flicker. Writer Doug Moench tried not to repeat himself, but didn’t match his golden collaboration with Paul Gulacy, and subsequent artists lacked Gulacy’s individual style. That changes with the stories reprinted here, covering 1979 to 1981 as Moench recovers his individuality, Mike Zeck’s art continues to improve and Gene Day arrives, first as inker, progressing to penciller on Volume 4.

The opening story indicates the tortured recent past, requiring six pages of synopsis to lay out Shang-Chi’s complicated and confused emotional state, and Moench initially draws on the past, with diminishing returns for Shockwave and Mordillo. The latter, however, enables Zeck to shine with some demented robots. It’s with the following story that Day begins as inker, and where Moench finds his way again, introducing Zaran, who’s since become a stock Marvel villain, but whose mastery of weapons provides first class opposition for Shang-Chi.

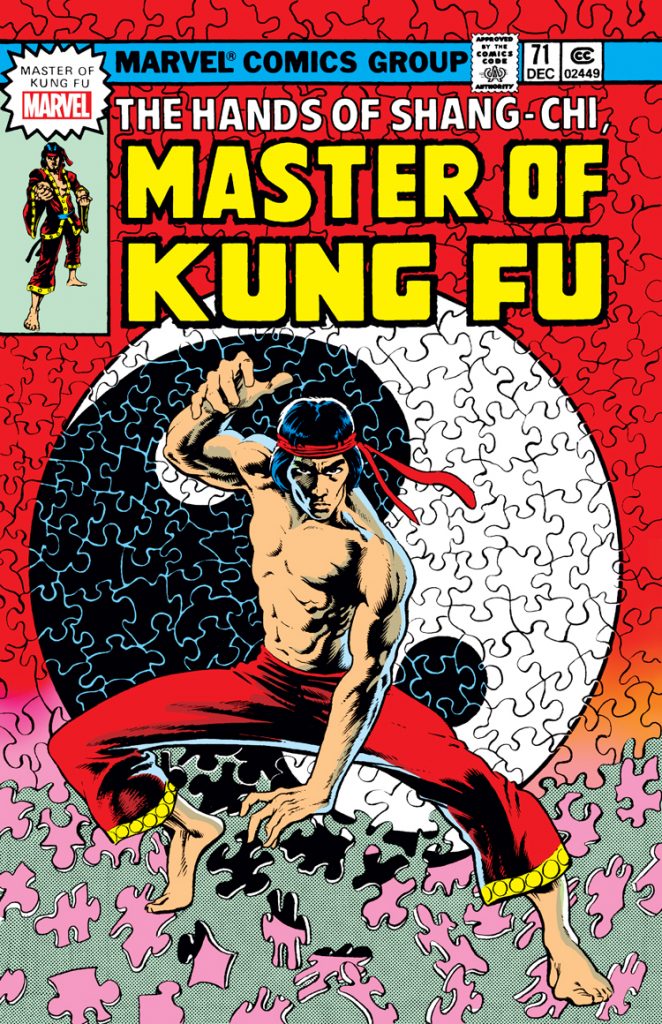

For some the entire concept of Fu Manchu as a Chinese crime overlord will be distasteful in the 21st century, but this collection really kicks into high gear with the suggestion he survived his death in the previous volume, and the centrepiece returns him in full. ‘Warriors of the Golden Dawn’ runs to seven exhilarating chapters, blending ancient history with a grandiose modern master plan, and the constant emotional undercurrent of Fu Manchu being Shang-Chi’s father. Moench writes creative action sequences amid a mood of distrust and tension, introducing questions about life and purpose, and works to a great pay-off. He introduces rifts between the cast beautifully, finds time for a Casablanca homage, and what the original editorial pages sardonically refer to as a post-opus letdown is anything but as Shang-Chi involves himself in New York’s gang problem.

Zeck grows as an artist throughout. The talented novice who began a regular series in Vol. 2 developed into someone notably good at laying out a page for cinematic effect, and infusing a sense of atmosphere, whether through climate or smooth action. He co-plots the final story, a neatly composed sequel to an emotive drama near the start. An alternate universe story in which Shang-Chi continued to believe his father to be a force for good, involves some muddy philosophising to bolster the premise. Rick Hoberg’s art lacks Zeck’s grace, and a compressed plot highlights the pulp aspects of the series without contextualising them adequately.

For the remainder, Moench manages to reconcile the essentially irreconcilable in allying Shang-Chi’s spirituality and search for a peaceful life with a succession of well plotted spy thrillers involving gaudy costumes and plentiful action sequences. Moench continues to invest in well considered new characters, the very knowing Shaft homage Rufus Carter oozing personality, and the lack of fill-ins is welcome. With the exception of the Fu Manchu epic, brevity is a watchword, nothing else extending beyond three episodes. A few stories never transcend their genre origins, but most do, and even at worst the poorer chapters have some human insight or interesting observations balancing the sometimes all too accurate period dialogue’s trivial irritation. There may not be quite the highs of Volume 2, but neither are there the lows, and that should be taken considering the overall quality of the series as a 1970s highlight. It results in a better volume with the quality curve upward for the start of Vol. 4.