Review by Frank Plowright

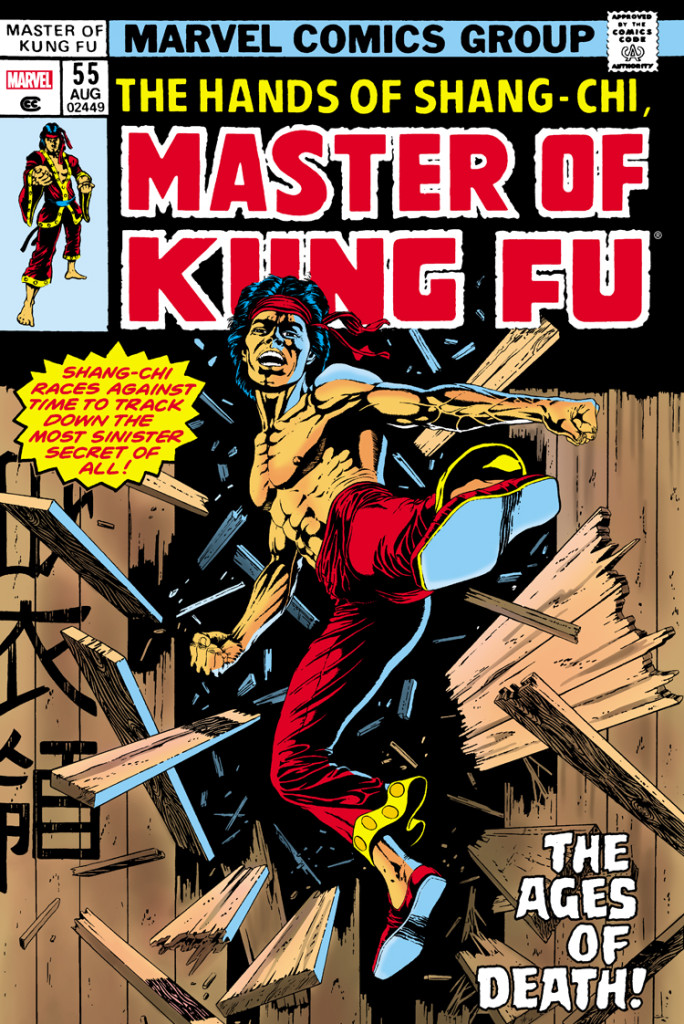

Almost half this Omnibus consists of the most fondly recalled sequence of Master of Kung-Fu, fourteen issues spanning 1976-1977 encompassing three stories by Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy. Rather than disappointing when presented again all these years later, this material has matured in the manner of fine wine.

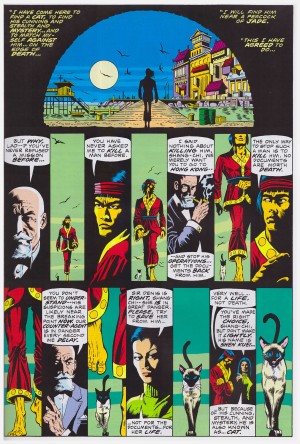

The visual sophistication employed by Gulacy remains impressive, building on the experimentation he’d employed on the stories concluding Vol. 1. These pages are steeped in atmosphere and memorably composed, their cinematic influences acknowledged by the presence of Marlon Brando, cast as a lead, and Marlene Dietrich and David Niven playing their parts. A single memorable issue has a sequence told as reflections on a pendant, there’s a fade and reveal from one woman to another using light as a motif, there’s the metaphor of a Siamese cat following Shang-Chi around Hong Kong, and a stunningly choreographed martial arts fight. Gulacy is excellent over the first third, with the caveat of minor variations to quality engendered by the deployment of a succession of inkers.

Moench’s narrative techniques were equally sophisticated for the time, although now more commonplace, such as panels flashing forward interspersed between explanations of how matters reached that point. He employs first person narrative captions rather than thought balloons, although more verbose than today’s equivalent, bestowing a contemporary quality. Moench also established a complex emotional triangle at the heart of the series, and doesn’t rest on his laurels, consistently creating imaginative kung-fu styled villains.

The Moench and Gulacy collaborations are lightning-paced action thrillers so good they remain five star material. While the series would again reach this plateau, it’s not in this volume, and a primary culprit is the art. Fill-in issues display Keith Pollard, Sal Buscema and Pat Broderick can lay out a decent story, but they’re not attuned to Moench’s flow in the manner Gulacy is, and when he in effect burned out, the problems begin. Jim Craig attempted to maintain the look of the series, never stinting with detail, but not quite capable, although in his defence he was constantly improving, and Gulacy was allowed time to develop that Craig never received. His brief stay is plagued by fill-in issues, which might have been more sympathetically placed elsewhere rather than maintaining the strict chronological publication order. Should the sins of the past be dogmatically repeated?

Craig’s not helped by the sole multi-chapter story he completes, incorporating an interesting idea, but not subtle by today’s standards. Matters improve considerably when Mike Zeck, who’d already contributed several fill-ins, becomes regular artist. He had the benefit of Gulacy’s shadow no longer hanging over the series, forges his own path, copes with a monthly deadline and his progress is rapid.

Zeck’s official start is two chapters into Moench’s homage to the Terry and the Pirates adventure strip. It’s complicated, hinges on complex emotional attraction, meshes characters old and new, and is ultimately bloated and overblown, not providing the twist to earlier events Moench intended. It occupies over a quarter of the pages, yet Moench only mentions it in passing during the course of a lengthy and informative introduction, indicative that he realises it didn’t work as planned. Far better to remember the Moench and Zeck partnership for their subsequent work, when Gene Day joins as inker, or for the initially puzzling, yet ultimately satisfying ‘Phoenix Gambit’.

This collection presents some of the finest comics Marvel produced during the 1970s, and in quantity enough to justify the high purchase price. At its worst the content is merely average. There’s more in Vol. 3. The Gulacy collaborations are also found in the paperback Fight Without Pity.