Review by Ian Keogh

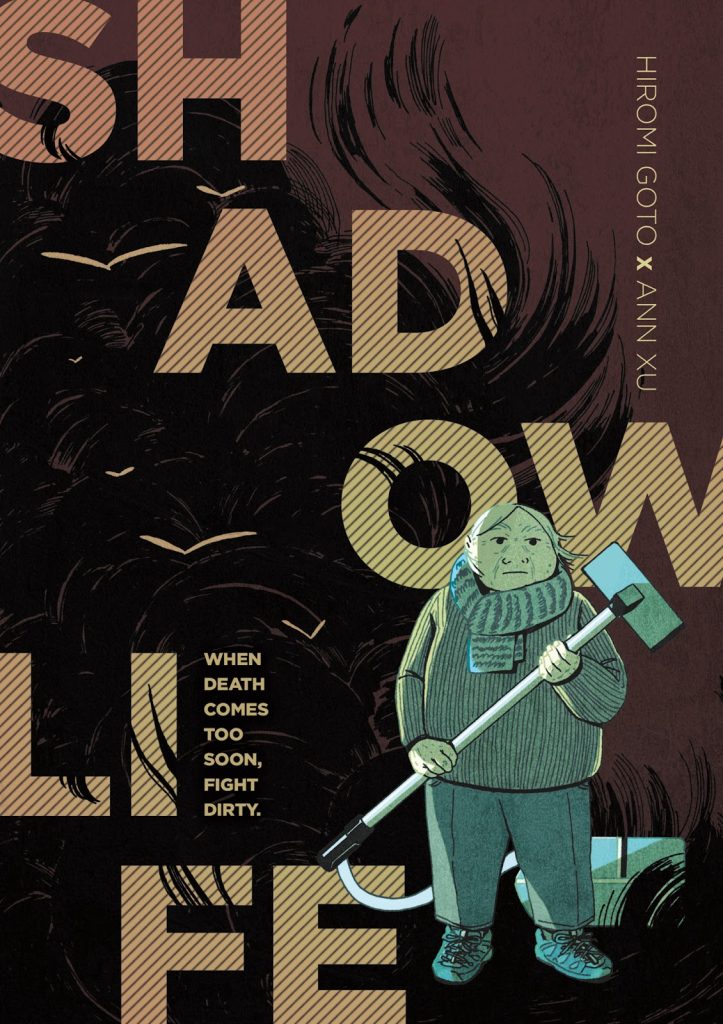

Shadow Life is a leisurely graphic novel deliberately set to reflect the slower pace at which the elderly Mrs Saito now lives her life. She’s widowed, and by and large accepts the limitations of age as she’s shown going about her business with the occasional grumble, although she’s generally remarkably optimistic.

Hiromi Goto’s script leaves much wordless, with Ann Xu’s simple cartooning showing what’s needed as Mrs Saito takes control of her own destiny in leaving assisted housing to move back into her own place. She knows her daughters disapprove, but is unaware she’s being observed by a shadowy creature able to change shape.

Goto and Xu do their jobs so well that the lack of any action in the conventional sense for around a quarter of Shadow Life is no impairment to enjoyment. It also heightens the shock when something remarkable happens, but Mrs Saito’s a formidable person as well as a stubborn one. However, after that incident she starts noticing things she’s never previously seen, supernatural occurrences, and a crisis point soon manifests. Things could take various routes from here, but what happens is testament to Goto’s individual and sympathetic sense of storytelling, as it leads to a reconciliation rather than a conflict. There is a conflict, though, more emotional than physical as Mrs Saito wrestles with the idea that she may be delusional.

Xu’s art is beautifully understated, especially when it comes to dropping bombshells, and she defines the surroundings well. Her people don’t seem expressive going about their business, which is possibly a cultural point being made about Japanese Canadians, but when a crucial moment manifests the emotion is there.

What begins as slowly paced domestic drama gradually picks up pace with supernatural intrusions, and just as Goto’s observations about everyday life have a unique twist, so does her treatment of the supernatural. Also well noted is the road to hell being paved with good intentions. Mrs Saito’s daughters aggressively impose their certainties about what’s best for their mother, and are frustrated at how she’s managed to remove herself from their supervision, yet all is not well.

The ending is the weakest section, and the only time the decompressed pace appears artificial in what’s otherwise a constantly charming and occasionally very funny story with humanity at its heart. It’s also nice to have a focus on an older person.