Review by Frank Plowright

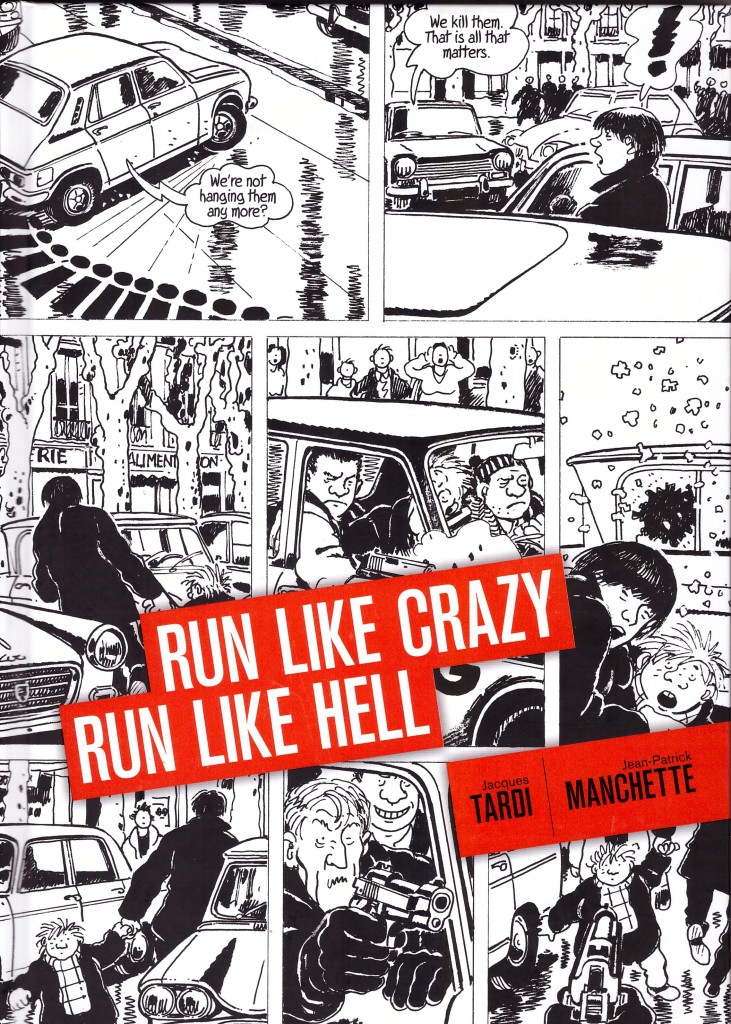

Depending on your point of view, Jacques Tardi’s third adaptation of a Jean-Patrick Manchette crime thriller improves upon the previous books or doesn’t quite meet that standard. The original novel was titled The Mad and the Bad for English language release, and is an earlier work than the previous adaptations. The pivoting point is Manchette’s plot having a far greater degree of both insanity and unpredictability about it. This is coupled with the customary strong characterisation and effective plotting.

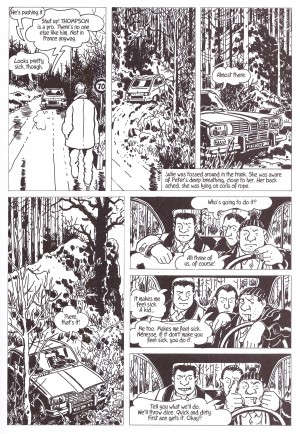

The wild card at first appears to be Julie, hired on release from a psychiatric clinic to be nanny to the infant Peter by his uncle Michael Hartog. Hartog inherited control of the family business when his brother and his brother’s wife died in a plane crash. While publicly seen as a generous contributor to charities who’s taking care of his nephew, he’s revealed near the start of the book to be plotting Peter’s demise to ensure sole ownership of the business. Julie is intended as the scapegoat, hired by Hartog as someone who’s considered a loose cannon given her history of mental problems, but he didn’t reckon on her self-preservation and protective instincts.

In fact apart from her repressions inducing a surprising capacity for violence, Julie becomes an avatar for rational thought, while the cast around her becomes ever more desperate, which is a fine touch. A further primary character is Thompson, another of Manchette’s flawed career assassins, introduced as the epitome of callous efficiency despite experiencing nausea when tense. Repression is also factored into his personality, and when his tensions release it results in a process of a disintegration that becomes physical.

Tardi’s visual depiction of the cast is wonderful. Hartog is forever angry, the ailing British Thompson gaunt, and Julie herself always impassive and unknown. He includes little jokes – the covers of his previous two Manchette adaptations are seen on a book rack – and great period detail, primarily via loving depictions of 1970s cars. Elsewhere the beautiful simplicity that’s characterised Tardi’s work for decades shows no sign of decline as he approaches his seventies, and the consideration given to designs is noteworthy. Architecture is fundamental to the plot, and a marvellously eccentric folly features heavily, so requiring some thought as to how it would work if it existed. Tardi’s mastery of black and white is exemplary considering he doesn’t take the easy option of drenching his pages in shadows, which requires thought about how to identify his cast members in crowd scenes. The eye is drawn by their darker clothing, but this necessitates Thompson changing his outfit, a moment seamlessly worked into the script.

There’s a deliberate slow-paced introduction as Hartog and Julie interact over the opening pages, before the plot receives an adrenaline injection that sustains it to the finish and ensures it lives up to the rush of the title. More so than Tardi’s other Manchette adaptations this is action-packed, and while the more fanciful elements of resilience in the face of extreme adversity might strain credulity, they more than have their precedents in crime fiction.

Crime is a genre that’s enjoyed a considerable renaissance in 21st century graphic novels, and even with a wide choice of excellent material, little of it matches Tardi’s work. Its longevity is cemented by a 2020 re-release combined with Like A Sniper Lining Up His Shot for the second Streets of Paris, Streets of Murder collection.