Review by Frank Plowright

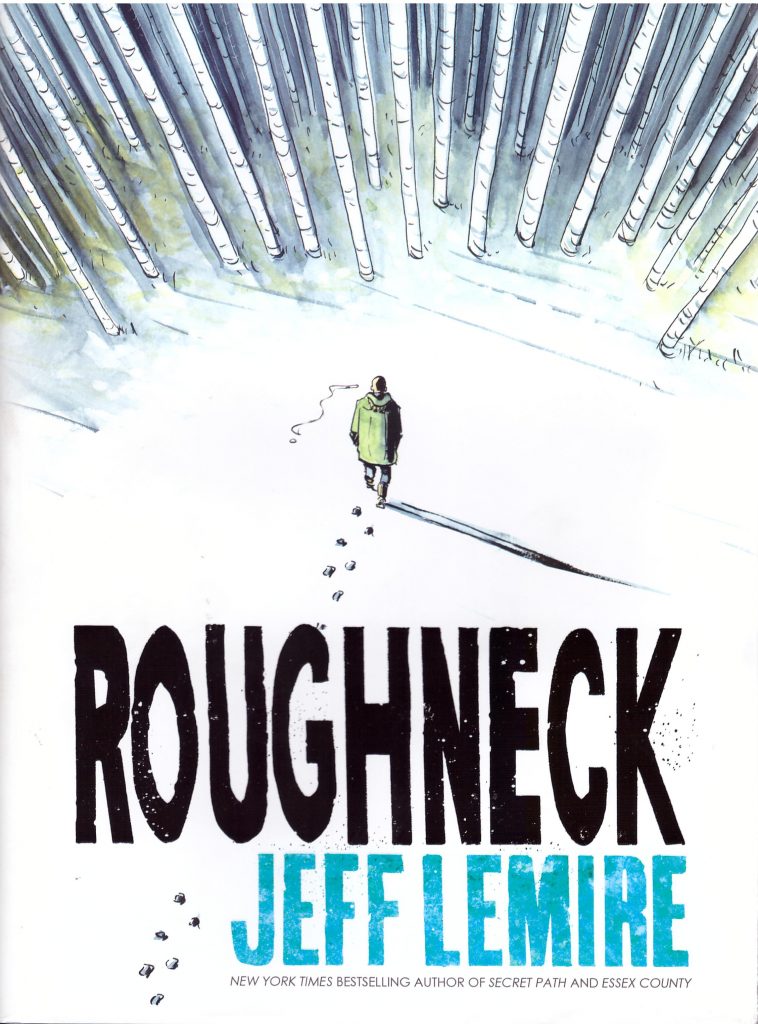

Jeff Lemire’s very impressive early graphic novels concerned loneliness, isolation and repressed feelings, and they all resurface in the thematically linked Roughneck. Ten years of subsequent writing experience has enabled Lemire to link the finely observed character studies and melancholy mood of that early work with a narrative tension that was largely absent.

Derek Oubliette earned a formidable reputation as a brutally effective professional ice hockey player, but with his career at an end he’s returned to his remote home town of Pimitamon in the Canadian wilds. He’s a violent, drunken and disruptive presence, taking shifts as a short order cook in the same diner where his mother worked years previously. He doesn’t dwell on past glories, but has had plenty of time to reflect on shortcomings, and part of Lemire’s understated personality construction is how regret and frustration manifest as violence. We see the harshness of an upbringing that made the man, and its results in the past and in the present.

Oubliette arrives at a turning point on the morning he’s released from jail after another unjustified, yet provoked, assault. Beth, the sister he’s not seen since her mid-teens also returns to Pimitamon, escaping a violent relationship. She comes with the family baggage, and has escaped from her problems in other ways. The Oubliette family haven’t entirely worn out their welcome, and after a further incident it’s considered best for all concerned if they spend some time away in a remote country shack. However, trouble is heading their way.

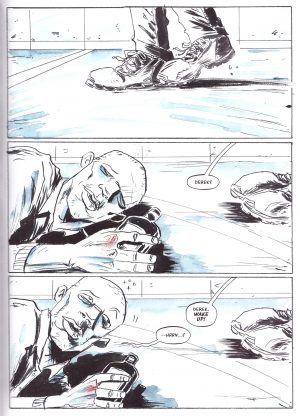

It’s no coincidence that Lemire’s chosen family name for his lead character translates as ‘dungeon’ in English, as this is a man trapped by his past, having learned his behaviour patterns to appease his monster of a father. Further allegory is supplied by Pimitamon being the Cree term for ‘crossroad’, and the artistic emphasis on trudging boots, representing characters on a journey. The passing of time is a method used to present monotony, reflection and the largely unvarying look of the environment. There’s also a reference to Lemire’s first long form work, Lost Dogs, Derek sharing characteristics with its protagonist.

Lemire is a creator whose best stories could only be told as graphic novels. Perhaps cinema at a push, but they wouldn’t work as episodic television, nor as prose because he unfurls them at a pace so ideally suited to the form, and his art is integral. His simple, blocky illustration instantly defines characters beaten by life, and his leisurely storytelling methods emphasise the space of their surroundings. The grey tones used occasionally give way to flat colour, reversing the traditional visual method of indicating the past, the purpose being to contrast Derek’s present-day null existence with a past that might not have been idyllic, but to which there was some life.

Both Derek and Beth are forced to confront their past, and the twofold tension stems from whether they’ll be able to overcome it, and in Beth’s case in particular if it will catch up with her. An astonishing evocation of mood elevates Roughneck to a story with great emotional depth, masterfully told by a creator whose work stands the test of time.