Review by Frank Plowright

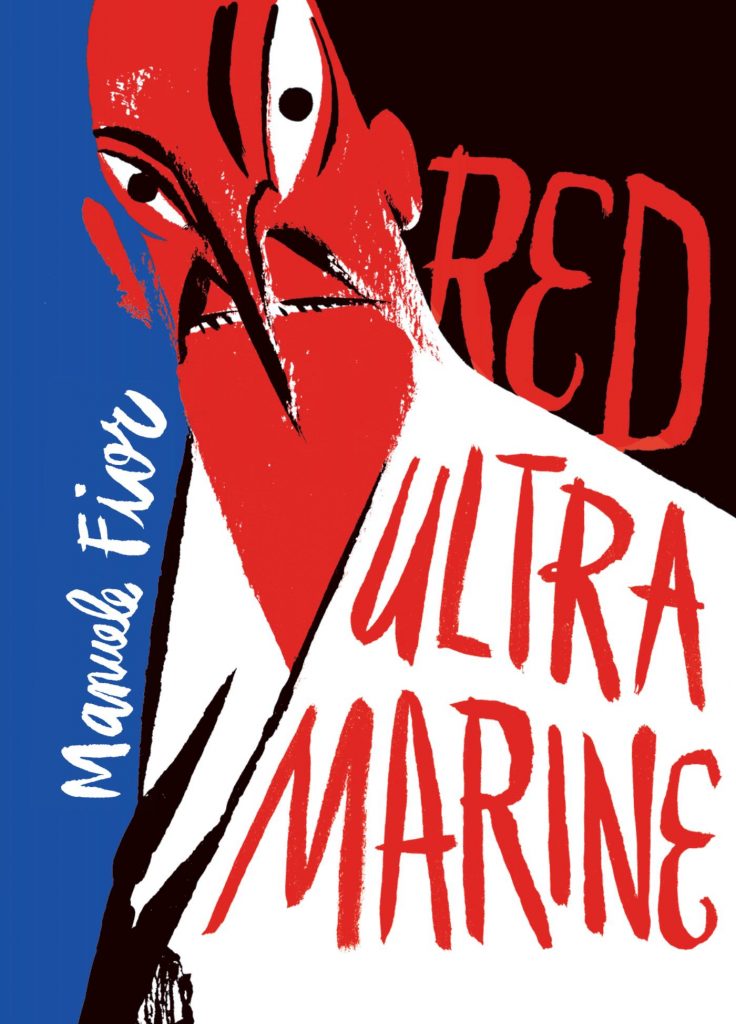

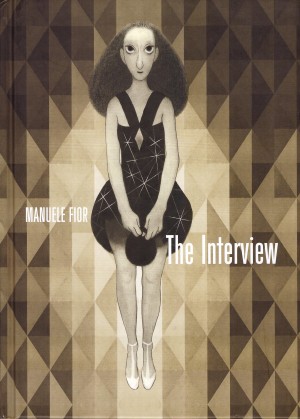

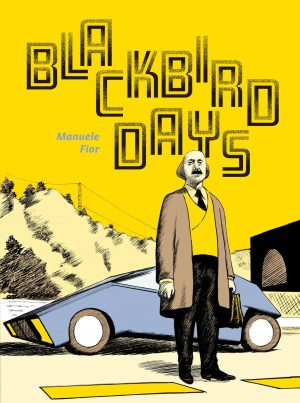

Fantagraphics’ very welcome translations of Manuele Fior’s thoughtful work continue with the first English language version of his 2006 début graphic novel, a strange Kafkaesque fantasy.

Fior alternates chapters of two very different stories, to begin with seemingly unconnected, referencing both the myths of ancient Greece and Goethe’s Faust. The dreamer Icarus disappoints his father, and in a later time Silvia is concerned about her boyfriend Fausto’s compulsions. He’s a conceptual architectural designer whose dedication excludes all else, pondering on the percentage of qualities defining a person. For different reasons, characters in both eras must deal with a labyrinth.

Red Ultramarine is a testing work, one in which we can possibly see the author’s personal contradictions reflected in the obsessions of his cast. Icarus is defined by a lack of ambition, while Fausto is ambition personified, and Silvia dedicated to saving his sanity. Fior has his own ideas and ambition, but this early in his career lacks the technical capacity to convey those ideas effectively. Silvia is concerned for Fausto, but the doctor one might presume is there to help instead makes quasi-mystical statements requiring Silvia to sift through them for anything of value. Fior’s later works mark him as an intelligent author, but the assorted symbolism offered here transmits as hollow and disconnected from what Fior wants us to pick up.

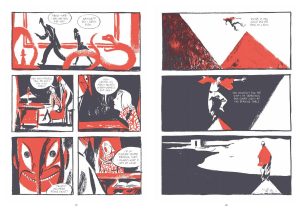

It may be an unsatisfying read, but Fior’s art is tremendous. Produced in black, white and red, offering some dizzying viewpoints and fragmented characters, it’s constantly engaging. Throughout his career Fior has been an artistic chameleon with the skill and technique to completely alter his style to match the approach he considers right for a story. Red Ultramarine is minimal cartooning, but shifts between assorted styles in the single volume. The ancient Greek pages are blocky, as if imitating urn illustrations, while Fausto’s ravings tip into abstraction, and some of Silvia’s scenes are stylised 1950s cartooning, loose and kinetic. The Doctor is brilliantly designed as individual, imposing and sinister, dominating any scene he’s in, while in other cases Fior creates the simplest of faces, sometimes barely bothering at all. Why is ultramarine mentioned in the title? The colour’s not used, so does the blue refer to mood, to Fausto’s deep-rooted depression? Is that even a phrase used in Italian? We can speculate, but it’s ultimately another unresolved mystery among several others.

Because Red Ultramarine is such a frustrating read it can’t be wholeheartedly recommended, but anyone who appreciates the art above any story ought be pleased.