Review by Allen Rubinstein

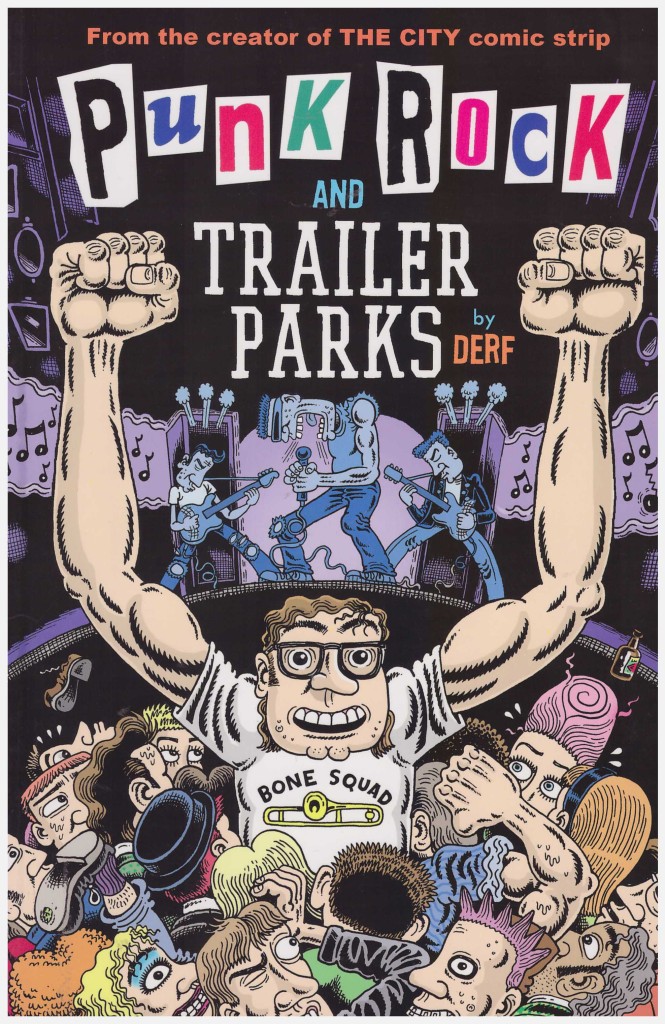

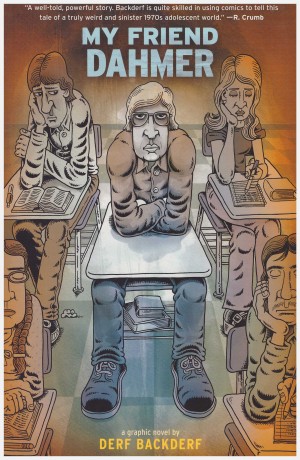

Cartoonist John Backderf, commonly known only as ‘Derf’, was a regular voice in alternative newspapers before making a big splash in 2012 with the bristling My Friend Dahmer, his memoir of attending high school with the notorious serial killer. Between the two, he put out a gem of a graphic novel, Punk Rock and Trailer Parks, a book so clever, heartfelt and seemingly commercial, one is left to wonder why it never connected with a larger audience (the ginormous arms on the cover may have been a deterrent). A simple coming of age story about a complicated teenager, the book is a humourous page-turner and works like gangbusters.

The story centers on fictional Otto ‘The Baron’ Pizcok, a protagonist who in sheer force of personality, could hold his own with ‘The Dude’ Lebowski. He’s a six-foot-four high school band nerd of supreme self-confidence who didn’t just create his own nickname; he invented a persona of mythic proportions, who defends the misfits of the world and records his farts on cassette. The Baron meets his destiny when he attends real-life legendary Akron punk club the Bank. In one night, he loses all of his remaining inhibitions in the slam pit, delivers a thrashing to two creepy stoners and then takes the Ramones out for burgers. He’s hired as muscle for the club, and thus the Baron has found his tribe in this rock and roll sub-culture.

The Baron and Ohio, however, are another story, as the ‘Trailer Parks’ half of the title concerns Otto’s underwhelming school and home life and whether or not he will flee the dead end, semi-tragic Midwestern streets after graduation. Appropriately for the creator of The City, Punk Rock and Trailer Parks is all about its setting, contrasting Ohio’s drunk, stoned and sometimes insane Midwesterners with the drunk, stoned and sometimes insane emerging punk scene. It makes perfect sense that a sheltered iconoclast like Otto would trade one group of going-nowhere oddballs for another, the major difference being that one is stifling and the other bursting with freedom. The latter also has him hanging around with the likes of Klaus Nomi, Wendy O. Williams, Rolling Stone rock critic Lester Bangs, Stiv Bator and the Clash. That this level of rock-geek wish-fulfillment never comes off as fan service is a testament to how organically the book rolls out its anecdotes and cameos.

Reading Derf’s short strips with their snippets of daily life and broad, boxy caricatures, few could have guessed he would emerge as a leading voice in graphic novels, but from the outset, the pacing and flow of Punk Rock and Trailer Parks is near flawless. Compressing stories into one to four panel bites for fifteen years taught him to cram a huge amount of information in a small space, and the sizeable ensemble supporting the Baron is vivid and memorable. In the year covered, we see developing relationships with his high school lust/crush, a pregnant nymphomaniac Christian, Otto’s near-sighted, ex-Communist elderly uncle who drives a lawn mower around town and best of all, a middle-aged “punk angel” who initiates a May-December sexual relationship with his majesty. (“I AM the Baron!!”)

Punk Rock and Trailer Parks is a story that crackles with life and compassion as its main character uses charm, talent and sheer brute force to pry himself away from the dire circumstances of his upbringing. It’s hoped the acclaim for Derf’s Jeffery Dahmer book has some buyers looking back to this earlier success. It would be wonderful to revisit Otto in young adulthood to see what other adventures the Baron had in store for him.