Review by Frank Plowright

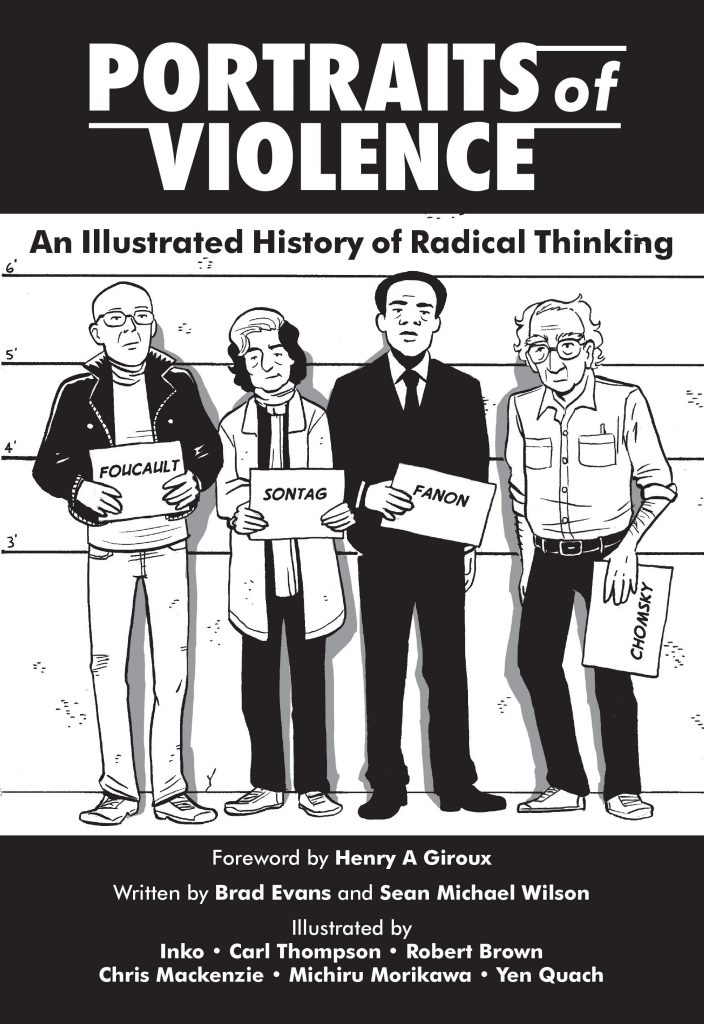

A sensationalist title perhaps obscures the parameters of Portraits of Violence, the academic tone more indicated by the subtitle. The types of violence people are perhaps most concerned about, domestic, street conflict and urban killing, aren’t the forms under discussion. They’re briefly addressed in Brad Evans’ opening and penultimate chapters, but the focus is state sponsored violence and repression, taking in colonialism, racism and ‘defence’.

Conceptually, Portraits of Violence starts with a wilfully contradictory approach. Despite most continuing titles thriving on violence, comics are an educational tool because of they can simplify, the combination of words and pictures stimulating a quicker understanding. Yet co-writer, political theorist and violence expert Brad Evans opens with what’s in essence a lecture, throwing readers in at the deep end. Evans employs academic language and obscure terms hindering comprehension, and contextualises beyond the response of most people. When seeing Rodin’s Thinker, do you consider “its ethnic, masculine and athletic form speaks to racial, gendered and survivalist discourse”? Or do you see a beautifully conceived and executed statue? What Evans has to say is largely thoughtful and valid, but he obscures his own message.

Evans’ narrative voice is distinguishable from the non-academic approachability of Sean Michael Wilson over the following chapters, which are more accessible. Yet because thinking about violence has been formulated by academics and philosophers this is no easy read except when considered in terms of the original books it reduces to their essence. We’re presented with biographies of important thinkers and their thoughts, and chapters in which violence and society’s response, largely accepting, is analysed, with the truths of Noam Chomsky particularly upsetting to the committed. He points out that beyond a certain comfort level not enough people care about the manipulation of elections and what’s done in their name, leaving a powerful elite largely free to follow their own agenda. No better proof of Chomsky’s conclusions could be provided than Donald Trump in the years immediately following Portraits of Violence’s 2016 publication.

The artists aren’t well known to the wider comic reading public, but cope well with representative illustrations for panels requiring captions rather than dialogue. Inko and Carl Thompson provide the sample pages on the basis of their illustrating more than a single chapter, but it’s Chris Mackenzie’s work on Hannah Arendt’s consideration of Adolf Eichmann’s trial that’s most distinctive, featuring a fine illustrative technique. It’s perhaps to be expected on a book about violence, but some readers may find the photographs reproduced upsetting.

21st century societies have become increasingly accepting of violence in the name of security, and Portraits of Violence draws attention to an important subject that we don’t consider enough. It explains forms of violence, influential thinkers, how humans drift into violence and how the media broadly condones the politics behind the violence while occasionally condemning the outcome. It’s worth noting that publisher New Internationalist was founded as a monthly news magazine in 1973 with the admirable principle of keeping social concerns at the heart of its journalism, later extended to their website and other publications. Is Portraits of Violence a missed opportunity? In some ways it is, as for all the worthiness and distillation of complex ideas, the dry approach still isn’t accessible enough for a general audience, so it’s likely to be preaching to the converted. That’s a shame.