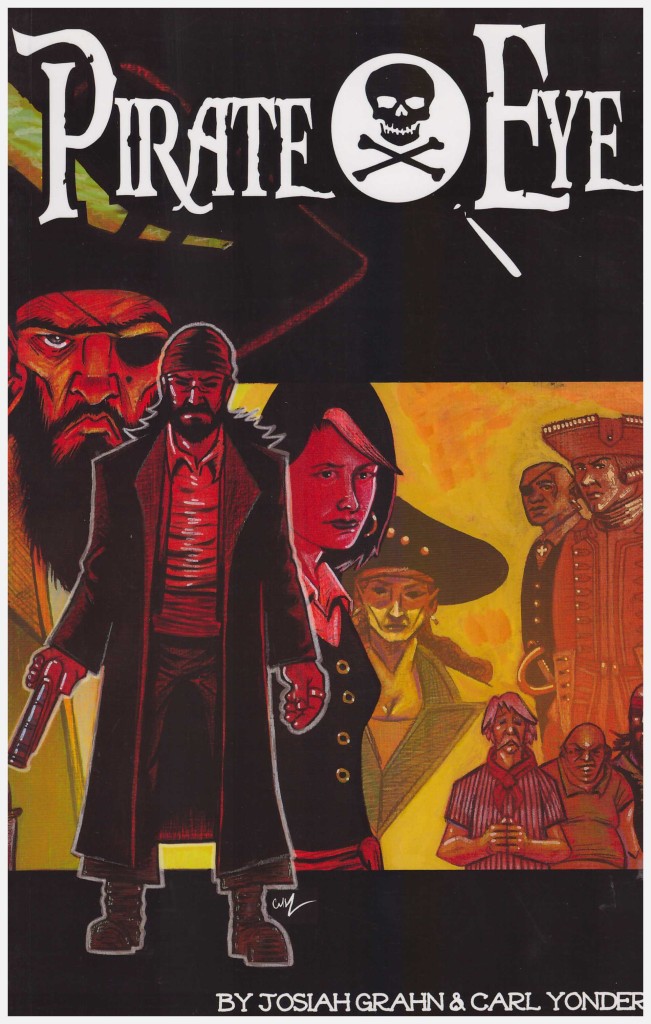

Review by Ian Keogh

There’s the germ of something good in Pirate Eye. Smitty is an 18th century pirate holed up in a port community in a never named location. His plundering days behind him, he now earns his way through life as what he calls a finder, locating people or items for a fee. He does well, but not well enough to avoid being in debt to the Parrot, the man who really controls the community, the governor notwithstanding. His philosophy is that his current trade isn’t too far removed from piracy, involving the same skill set, except now he’s finding things legally, and while not entirely avoiding trouble, it’s certainly diminished.

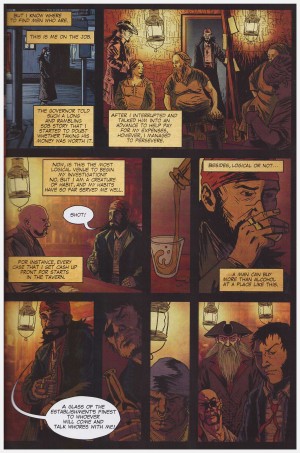

Writer Josiah Grahn gives Smitty the expected downbeat character associated with his trade two centuries later, and places some pithy observations in his narrative captions. It creates a rounded and almost likeable personality in the square circumstances of his background. Grahn’s plots well suit his lead character, drag the audience along, and have a twist in the tail. So where’s the problem?

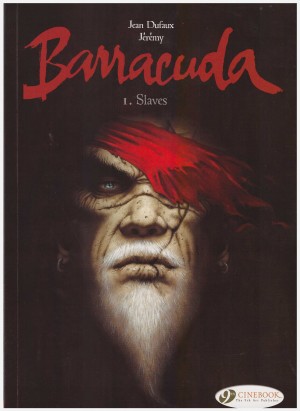

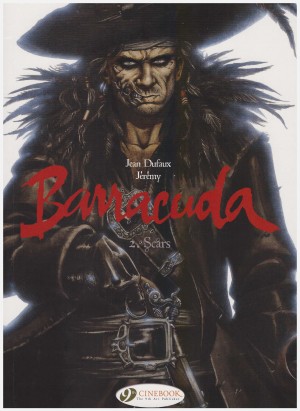

Carl Yonder’s art could be much improved, and one day probably will be. He has a talent for character more reminiscent of European comics than standard US material, and can distinguish his cast. For this collection, though, he draws as much as possible in close-up. The viewpoint hardly ever pulls out further than a head and shoulders shot, and frequently draws in from that. Full figures are a rarity. This may be to avoid drawing anything else, or may be a misguided impression of increasing dramatic tension. The result is pages with little variation, and the impression of extremely dull material is heightened by Yonder’s gloomy colouring. Furthermore, artists who’re going to draw something once then photoshop it throughout the remainder of the book should perhaps at least avoid doing so on the same page.

The other off-putting aspect of this collection is the cheapness of the production. It consists of what was originally published as four one-shot comics, but these are the actual comics, scooped up from the warehouse boxes and rebound as a book, advertising and promotional material and all. The art and dialogue frequently disappears into the gutters of this new binding.

Unless he develops a new method of laying out pages, Grahn is more worth keeping an eye out for than Yonder.