Review by Frank Plowright

Pinocchio is a remarkable use of the comic form to deliver a new and dark variation of what was already quite the bizarre and demented story. On no account dip in looking for Disney cheer.

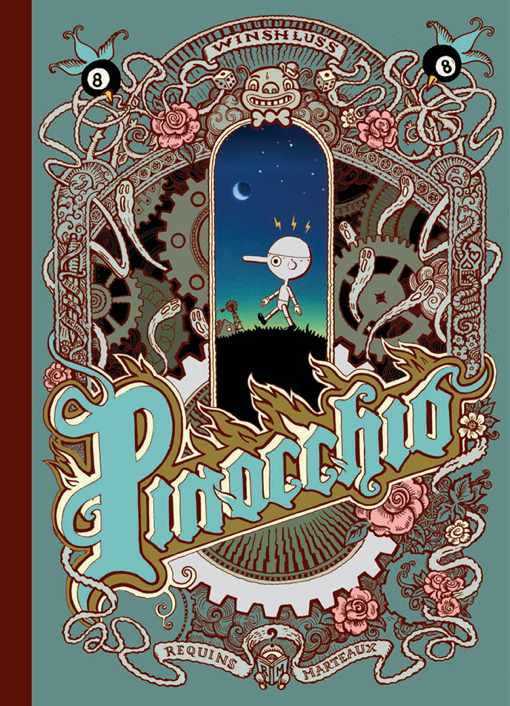

The variety of art styles alone is impressive. Winshluss is the alias adopted by Vincent Paronnaud, and the primary style has echoes of early 1930s animation, brightly coloured in pastels, yet with a slightly off key and disturbing quality. This is spliced with flashbacks of a more painterly type, scratchy black and white strips, full page storybook style illustrations, sepia-tinted pages… The accumulated heady concoction is promised by the cover, surely a tattoo in the making.

The modifications Winshluss makes to the original material are equally mind-expanding. This Pinocchio is a small robot boy created by a downtrodden engineer as a home help for his less than grateful wife, although she eventually discovers a use for his long nose. It’s a costly discovery. Gepetto, meanwhile, is touting his design to the army as a prototype soldier. This sordid counterpointing is key to the world constructed around Pinocchio, where few intentions are pure. This includes Jiminy Cockroach, here not the conscience of redemption, but an exemplar of the worst humanity has to offer, who takes up residence in Pinocchio’s head. As Pinocchio stumbles through his environments there’s a secondary effect on Jiminy Cockroach.

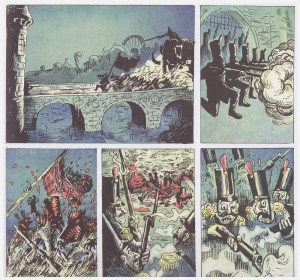

Much of the book is wordless, and Pinocchio himself a passive participant in his assorted absurdist experiences. For a significant period he’s hanging from gallows, a mute observer as Winshluss presents the rise and fall of a society. This Pinocchio resembles nothing so much as an out of control nightmare, with monsters, chases, violence and tragic occurrences. Yet this isn’t stream of consciousness, but densely plotted with seemingly forgotten cast members recurring at pivotal moments.

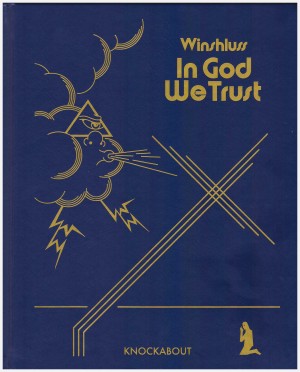

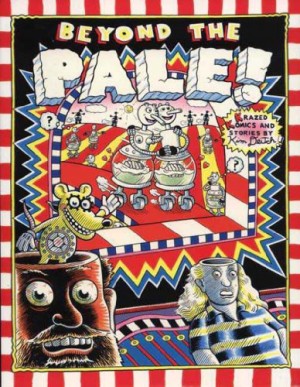

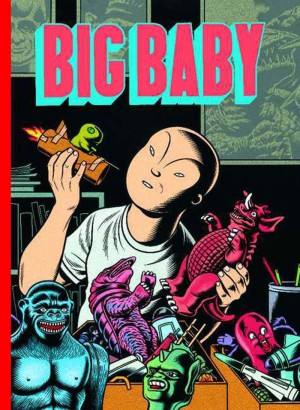

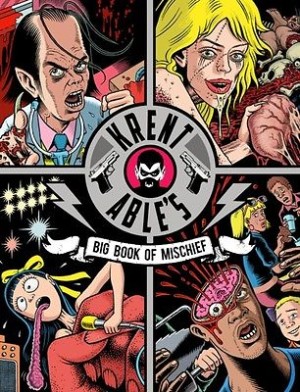

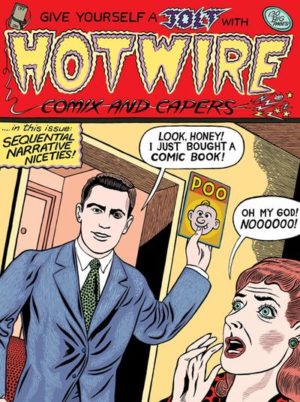

American underground comics are a definite touchstone, with their freedom of expression, their taboo-busting material and the similarity of much of the best art to classic newspaper stylings. It would only take a different artistic style and Snow White’s horrible story here could be straight from an S. Clay Wilson comic. The cover could be an ornate Greg Irons design. Knockabout were the primary importers of underground comics to the UK, and Last Gasp published them in the USA, so this co-production has a home with legacy.

The publishers haven’t stinted in supplying a beautifully designed hardback package on heavy paper stock and mad endpapers. The lavish production reverses the deliberately trashy content.

Pinocchio won’t hold universal appeal, but those who do take up the challenge will be swept along on a dark and continually surprising journey.