Review by Frank Plowright

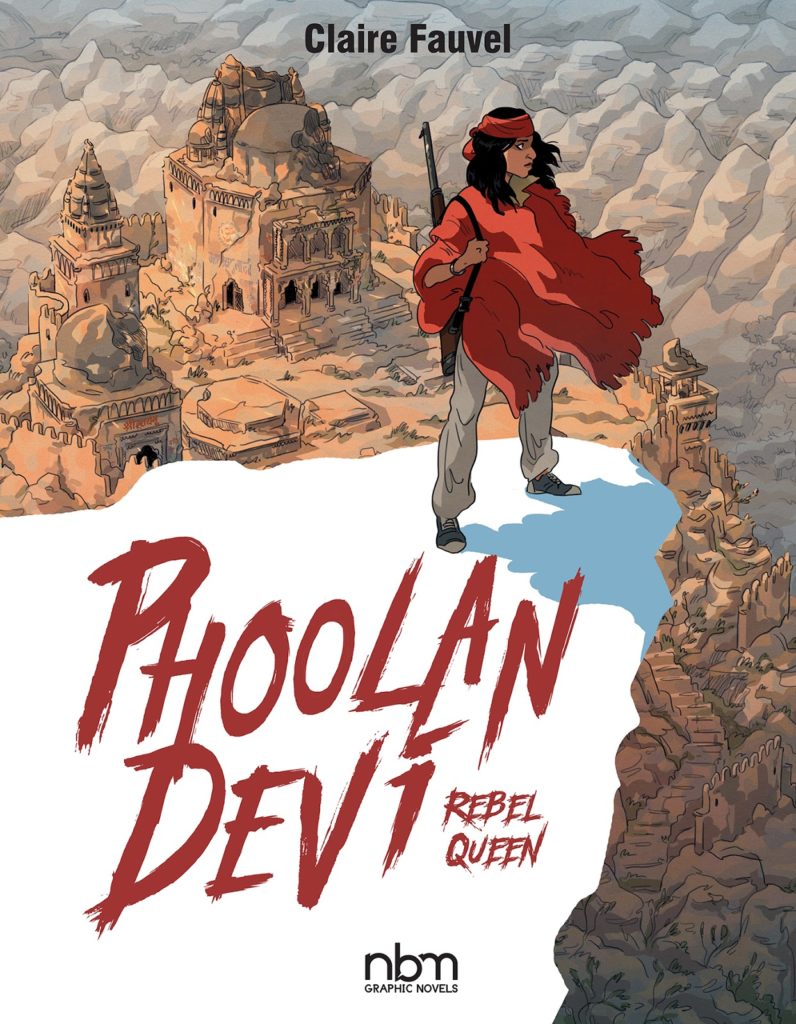

Phoolan Devi’s incredible life resulted in an unauthorised film biography and an autobiography she dictated herself, on which Claire Fauvel bases her graphic novel, using Devi’s own words. In Fauvel’s introduction she describes reading the autobiography as a kick to the stomach from which no-one emerges unscathed, and much the same applies to her adaptation. For all India’s recent status as a world economic power, many aspects of its society, particularly with regard to women and children, still cause concern in the wider world, where the Hindu caste system is seen as promoting inequality.

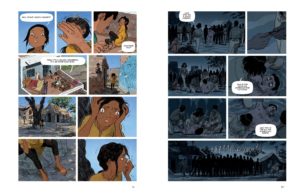

Rebel Queen opens in 1994 with Devi in prison, but learning she’s about to be released, before winding back the years to her late 1960s childhood. She was born into the Shudra caste, the lowest of all in Hindu rankings, only a step above those considered untouchables. The left hand sample page represents only the minor indignities she had to endure, this inexcusable behaviour from a respected village elder. Married when still a child, much worse was to follow over the next several years, and under the traditions of society it’s the woman’s fault. It would take an Indian not to be outraged. Despite the horror, the young Phoolan was lucky she had a feisty mother to look out for her. The subtext is that many didn’t. The next portion of her life begins when she’s abducted by bandits, and they’re willing to do what the authorities don’t, providing justice outside the law. As romantic as it sounds, that’s but a temporary interlude.

Fauvel has a sketchy way of drawing people that takes some getting used to. It’s not conventionally beautiful comic art, but this isn’t a conventionally beautiful graphic novel. It needs the roughness to give truth to the degradations, and when needed, Fauvel can supply considerable detail to cement a location. She doesn’t hold back when picturing Devi’s suffering, bearing in mind that for most of the book she’s a victim even if society doesn’t see her that way. 75% of the story is told before Devi becomes empowered.

It’s to Fauvel’s credit that at times Devi’s exploits are so fantastic, so thrilling that for a few pages it’s forgotten that this is a biography, before we’re brought back to Earth with another atrocity. Devi isn’t without blood on her conscience, but she became what she was due to others. We’re left with a remarkable story that’s educational in the best sense and a graphic novel that succeeds in provoking outage as intended. Much of what Devi endured in the 1960s and 1970s remains commonplace today in a country where rapists and killers of women aren’t officially sanctioned, or rarely receive sentences anywhere near commensurate with their crimes. Anything highlighting that is worthwhile.