Review by Jamie McNeil

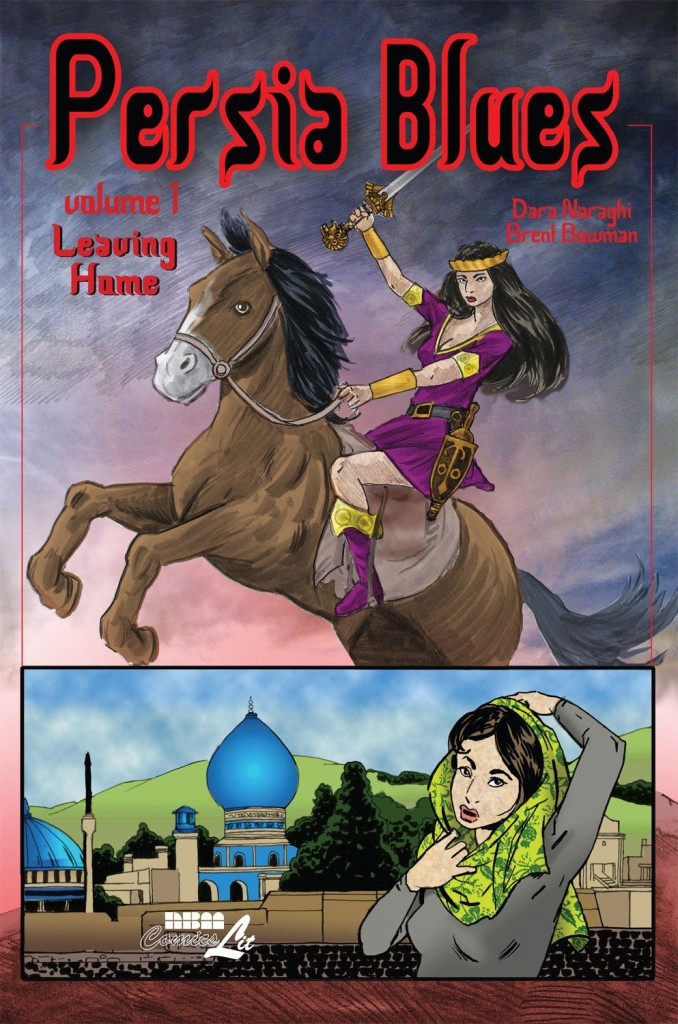

Minoo Shirazi is a young women who lives in the Here and There. “Here” is a fantasy world set in Ancient Persia where she is Minoo the adventurer, the warrior, the lover, and the maker of her own destiny, yet she still longs for greater purpose. “There” is the real world of modern Iran over a period of twenty years, where she is Minoo the daughter of an Iranian History professor watched closely by the government, a young woman struggling to find purpose within the boundaries of a faith she is forced to believe in and whose tenets she must adhere to. What the Minoo in both Here and There have in common is that both have suffered personal tragedy, both have a broken relationship with a family member they wish they could mend, and both long to be part of a greater purpose that allows them to be as they really are.

Penned by Dara Naraghi, it is a look at a young woman caught between cultures. Here symbolises her journey of discovery in the USA, her lover Tyler simultaneously real and fictional. Not only is she finding herself, but exploring her Persian identity depicted as the Persian deity Ahura Mazda sending her on a sacred quest.

Persia Blues is illustrated entirely in black and white by Brent Bowman, who distinguished the two settings by rendering the fantasy world of Here with highly detailed landscapes and fantastical creatures from Persian myth. By contrast, the modern Iran in the land of There has no grand flourishes, makes frequent use of dark shades, is less detailed, and by far the more evocative of the two styles. Here feels detached and it is difficult to sympathise with the transitions Minoo is going through in her new life, displayed as fantasy when it isn’t really. Bowman captures the sense of oppression and restriction Minoo and others experience under the rigid laws of modern Iran in There, the realism garnering more sympathy.

It’s an interesting concept, and as someone of Iranian descent himself, this appears to be Naraghi’s commentary on his own journey. It feels deeply personally and since Minoo is literally caught between two worlds, this is something we can all relate to and the strongest element of Naraghi’s story. Persia Blues shares some commonalities with Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis – an Iranian woman growing up at a time when the political and religious landscape is changing, hiding personal beliefs and longings for freedom from the morality police before finding freedom in another country.

Two things let this story down. The fantastical world of Here is not meant to be realistic but Bowman’s choice to use two different styles hinders the story. The emotional explorations Minoo undergoes in the search for her mother are simply not as convincing or as powerful as the anger, sadness, and hope her alter-ego experiences. While he is skilled, it makes for a stilted transition from era to era. The second is that Naraghi, as a male, writes from a female perspective. As an Iranian male this avoids obvious stereotyping, but makes Persia Blues slightly less authentic than Satrapi’s autobiographical female perspective in Persepolis.

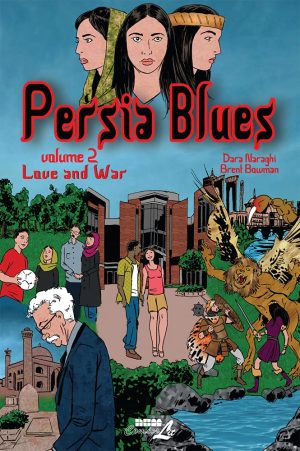

What is admirable is that Naraghi knows life is hard for anyone in Iran, but especially hard for women. It is incredibly brave to write about something as deep and personal as this, whatever perspective you use. Minoo Shirazi’s life in both Here and There unfolds further in Persia Blues: Love and War.