Review by Graham Johnstone

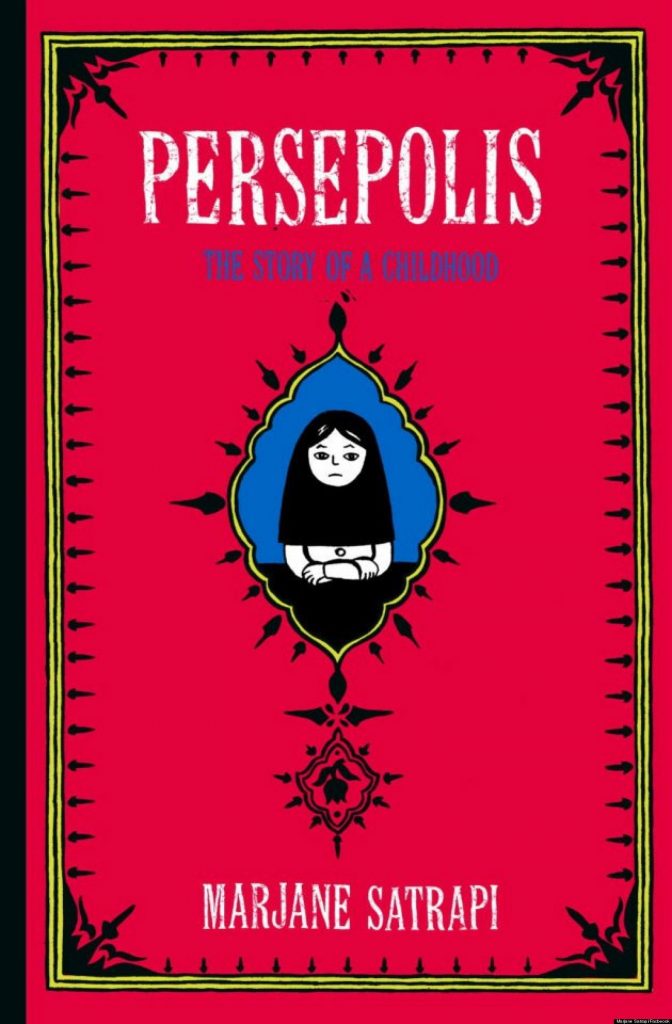

Marjane Satrapi’s acclaimed Persepolis tells the story of Iran’s political and religious upheavals, through the eyes of young ‘Marji’. It’s a story most readers in the West will know primarily from media reports, emphasising the fundamentalist Islamic regime. However, as Satrapi notes in her introduction, a minority of extremists don’t represent a whole country, and she’s well placed to tell a different version of the story. Her parents were secular liberals, claiming lineage from Iran’s last Emperor. Wealthy enough to drive a Cadillac, they still supported the (ostensibly) Marxist uprising of 1979 that overthrew the Shah, before, ironically letting the fundamentalists seize control.

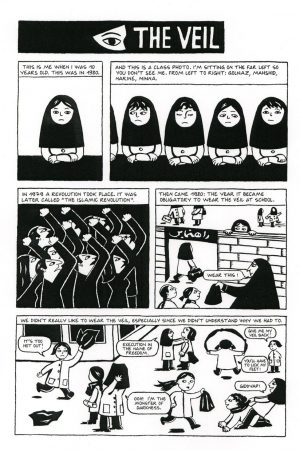

A series of short chapters begins with ‘The Veil’, surely the most powerful symbol of the Islamic regime. Marji was ten at this point, old enough to remember life before the veil, yet young enough to be baffled by its introduction. Satrapi’s light touch is highlighted by the playground scene of girls improvising uses for this new accessory – relatable to anyone who remembers their childhood.

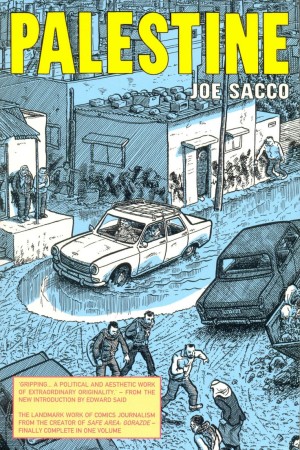

After this, we rewind to before the revolution and hear of key events as they enter Marji’s world: protests against the Shah, and his attempts at reform; families thrown into poverty, and members killed; and people imprisoned by one regime, released by the next only to be rearrested. The ostensibly Marxist uprising is railroaded by the fundamentalists. All this is exacerbated by the Iran/Iraq war, manipulated by the West, and prolonged by the fundamentalists to maintain their hold on power.

All events are dramatised in terms of Marji’s life, and often re-enacted in the playground – “your father betrayed my father”, and so on. As Marji reaches her teens she learns of the more shocking practices. The chapter ‘Dowry’, for example, shows the state’s appallingly ingenious way round the prohibition on killing virgins. Other aspects are dealt with in a light-hearted manner, providing welcome relief from the tension. Border issues and restrictions play out in her parents’ ingenious method of smuggling in posters of “punk” (hardly – but don’t tell Marji) singer Kim Wilde. With all these dangers, exacerbated by Marji’s own outspoken attitudes, her parents start looking at extreme measures to protect her.

Persepolis is a memoir, not a documentary, so we’re given Marji’s partial understanding of events. Satrapi the writer knows the limitations and foregrounds the subjectivity – most of the stories she tells are what young Marji has been told by others – relatives and family friends, even children in the playground. In one chapter she overhears her mother’s phone conversation, as if to emphasise the idea that this is – in the most literal sense – one side of a story. Marji’s questioning nature is also useful in the book for unpicking and arriving at second opinions about things she has heard.

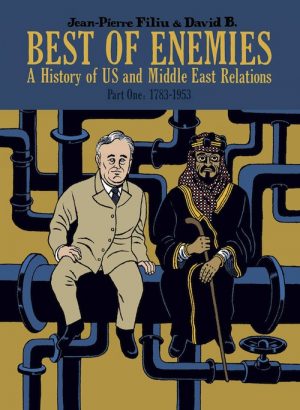

Clearly Satrapi has powerful stories to tell, and her art is as deceptively simple as the stories. She’s a powerful visual storyteller, with a ‘woodcut’ style, surely influenced by ‘David B’, (of L’Association who first published Persepolis), and (actual) woodcuts by, say, Käthe Kollwitz. We see her finesse in capturing from simple facial expressions the different reactions of her classmates to the addition of the veil to the school uniform (pictured). Her faces and postures are expressive, and she turns her hand to whatever is necessary, often iconic, symbolic images of e.g. boys being blown up in battle. The style also fits perfectly with the child’s eye view of the story.

Published in France as four albums, in English this was the first of two, later gathered in a single volume.