Review by Frank Plowright

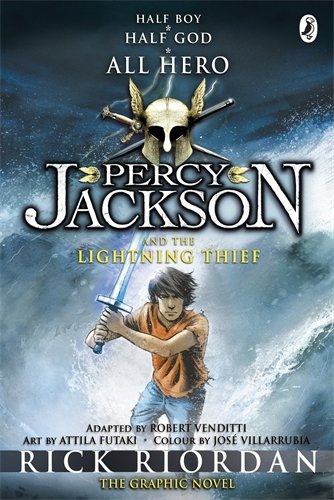

This adapts the opening volume of Rick Riordan’s immensely successful series of children’s novels, and Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief weaves quite the spell. You start by noting all the similarities to Harry Potter, given that little twist to avoid accusations of outright plagiarism, but as you’re doing so it sucks you in, and it’s around the midway point you realise that you’re hooked.

So, the similarities first. Percy Jackson is a 12 year old boy who doesn’t really fit in anywhere. He’s awkward, shy and quick to anger, but absorbs that folk around him consider he has a destiny. How is it that he’s so informed about the old Greek and Roman Gods, and seemingly magical events occur around him? Then, wouldn’t you know it, creatures from those myths begin manifesting in the real world, and it appears a powerful magical entity wants him dead. There’s a further cast adjustment underlining those Harry Potter comparisons before Percy finds himself at a summer camp where Greek myths flourish. Except they’re real.

The comparisons continue, but the bigger plot is that everyone who ends up at the summer camp is believed to have been sired by one of the Gods, who’ve now relocated lock, stock and kaboodle to the USA. Ancient habits die hard, and the Gods still put it about a bit with mortal woman. Anyone sired by them is a demi-God, and still immensely powerful. The fathers, though, rarely claim their own.

Shortly after we head into the quest part of the book, when Harry, Ron and Hermione… Sorry, Percy, Grover and Annabeth set off across the USA, and the title’s meaning is uncloaked. Riordan, and by extension adaptor Robert Venditti, cultivates tension by revealing something to Percy and the readers, while supplying a buddy bonding trip with magical intrusions.

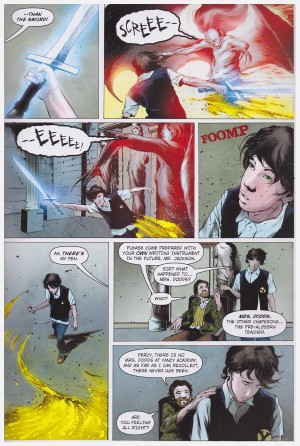

Hungarian artist Attila Futaki is very good indeed, if sometimes over-reliant on picture reference for posing his cast, leading to some stiffness. On the other hand it ensures consistency throughout, and Futaki’s depiction of the various other-worldy realms is suitably imposing.

The plot’s hovering secrets aren’t very deftly disguised, and without also reading the novel it’s difficult to know who’s responsible. Any child with a basic knowledge of Greek myths who’s paying attention will figure out who Percy’s father is, revealed around halfway, and an element of prophecy may fool younger readers. The derivative elements diminish as the book continues, and while they might make sound financial sense, there are enough good plot aspects here to suggest most similarities could have been dispensed with to little narrative detriment.

This adaptation was successful enough to prompt two sequels to date, starting with Sea of Monsters.