Review by Ian Keogh

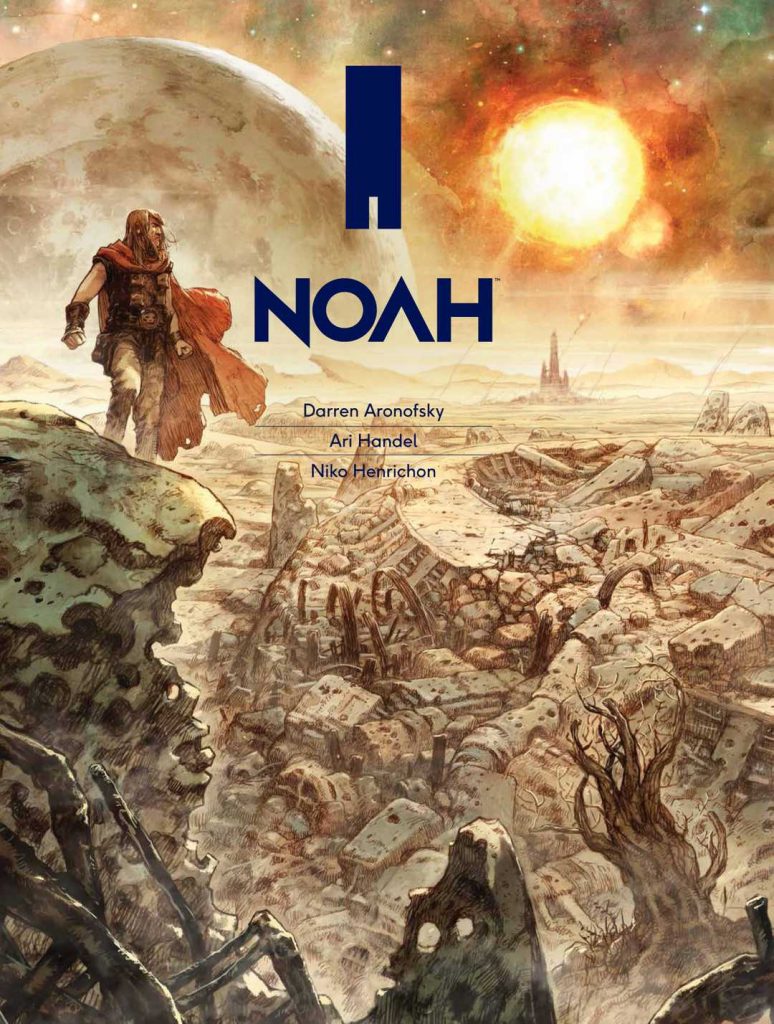

Film maker Darren Aronofsky’s extrapolation around the biblical story of Noah was released to a positive reception in 2014, but he had more to say on the man, his mission and the environment, and not all of it made the film. Artist Nico Henrichon worked from an early script, and while the basis is the core of the film, it involves some fleshing out of Noah’s visions, his status as a righteous man and the contempt he’s held in by those in the cities who consider themselves civilised, represented by Tubal Cain and his plundering army. As he did on the film, the graphic novel is Aronofsky’s collaboration with fellow writer Ari Handel.

Noah is literally a man in the wilderness, wanting to live a simple life that honours his God, but constantly beset by the violent intrusion of city dwellers. Interpreted in this way, and adding the notion of climate catastrophe, Noah’s is a very modern story. He’s beset by dreams of God punishing the world for its sins, unleashing a mighty flood in which only he seems to be able to make the surface, but how is he to survive what kills everything? God eventually supplies the method and the start of the means, yet what the creators bring out is the sheer backbreaking labour involved in building an ark to contain a pair of every living species.

Inconsistencies in Noah’s story are ripe for pointing out, but Aronofsky and Handel treat it with respect, accentuating Noah’s devotion and commitment to his task, and the toll it takes on him. The Old Testament is packed with stories of a God demanding tests of faith, and while this isn’t as explicit in Noah’s case, he still concludes there’s a heartbreaking decision to make. To personalise Noah’s story requires a fair amount of background colour, so while remaining true to the Noah of the Bible, he’s surrounded by characters other than his family, instituting conflict and moral uncertainty. An ethical authority holding groups of people collectively responsible for the shortcomings of some is harshly applied, and some of Noah’s more extreme decisions cruel, his interpretation of the flood being that all mankind should be wiped out, just the creatures preserved to reinstate paradise. However there are scenes where Noah moves uncomfortably close to a form of fantasy hero, especially a tense sequence when Tubal Cain and his army intend to take Noah’s work for their own.

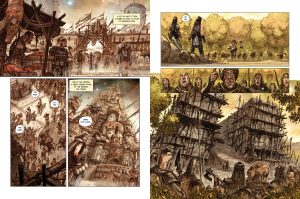

Some scenes display a suitable epic biblical scale from Henrichon, his vistas grand and his battles never knowingly under-populated. There’s a European style looseness to the way he portrays people, and it’s ideally suited to fighting and movement. The ark’s design, although it’s never referred to by that term, is taken from the Noah film, and it’s a more realistic construction than the fairy tale image usually associated with Noah, a vast pragmatic lump, the scale shown during the building process. That feeds into the creators deliberately moving the imagery away from a traditional biblical drama to something more down to Earth.

Aronofksy’s plot eventually compels us all to judge Noah and his beliefs. Is he deluded? His dreams proved right, but are his later pronouncements nothing more than assumptions? Why would anyone follow a God so cruelly demanding? Each reader will reach their own conclusions, but what Aronofsky, Handel and Henrichon have produced is thought-provoking, and that’s what ultimately makes it memorable. As a sidebar treat, it’s well worth checking out Handel’s contribution about Santiago the monkey on The Moth site.