Review by Ian Keogh

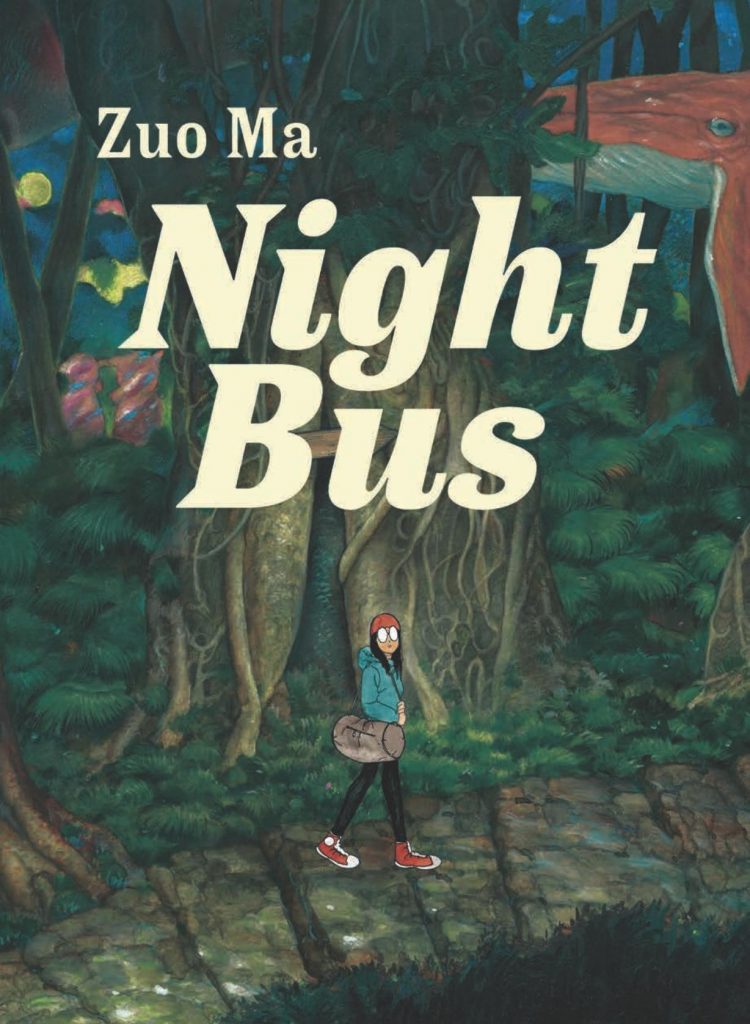

Although titled after the longest piece presented, the English edition of Night Bus combines what were originally published as two books in China. The anthology of short stories Walk was published in 2013, and the graphic novel Night Bus followed in 2018. Publishing them in one edition makes sense as they share many similar themes, especially focussing on Zuo Ma’s grandmother, an important figure in his life. The presentation isn’t chronological, ‘Night Bus’ appearing relatively early, and while autobiographical recollection and biographical notation, everything Ma produces is cut through with a surrealistic streak, as if to undermine any perception of self-importance.

He is a very self-conscious creator, never satisfied and constantly taking opportunities to revise or revisit his work. It’s no coincidence that this collection ends with a story very similar to the one opening it, Ma reworking ‘Walking Alone’ more concisely three years after the original. Chester Brown, and Rob Walton’s considerable reworking of Ragmop for graphic novel publication are the only other examples that comes to mind of creators substantially reconfiguring what they’d produced earlier. Ma does the same, adding fifty pages to the Chinese version of ‘Night Bus’ and restructuring the story for English publication. That feeds into Ma’s world of introspection and reflection, and actually echoes the story’s theme. It’s an allegory for his grandmother’s dementia presented as a confusing bus journey taken as a younger woman in which she’s not let off where she wants to go, and nothing matches her memories, in part a commentary on the pace of change in modern China. Ma inserts himself into the narrative, both as a creator and a young child as the memoir mixes with the dream. He supplies other visual metaphors for his grandmother’s condition, such as balance, and although meandering (another metaphor) ‘Night Bus’ is also poignant, regretful and heartfelt, and in places resembles the fantasy of a Studio Ghibli film.

If the stories meander into the surreal, the art is very much the opposite, with Ma a structured creator producing incredibly detailed illustrations, with scenery, whether urban or rural, very important to him. His greatest artistic strength is the definition of location, with his people less distinct, but the images throughout are dense and beguiling. A progress can be seen when comparing earlier work with later pages, which are tighter, but there’s a consistent use of black ink for mood.

Many of the short stories that follow ‘Night Bus’ appear in hindsight to be trial runs for elements included in the longer piece, although they stand up well enough alone as reflection and anxious dreams. While monsters are prevalent, in most stories Ma has something to say, with ‘The Beetle and the Girl’ very successful in connecting the two title characters while also making a point about the harshness of school life. The central horrific sequence could almost be by Richard Corben.

Notes in the back of the book indicate that until the original Chinese collections Ma’s work seems to have been restricted to relatively obscure anthologies, which is puzzling. Collectively they have a weight and a pastoral evocation unusual for comics and well worth dipping into.