Review by Graham Johnstone

Neurocomic is an accessible guide to the human brain and nervous system credited entirely to neuroscientists – Matteo Farinella and Hana Roš. There’s no breakdown of roles cited, but online biographies note Farinella’s move into science education and visualisation, suggesting he’s the main storyteller, with Roš bolstering the neuroscience.

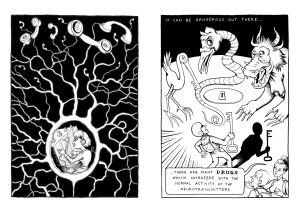

His angle is an access character sucked, like Alice, into the ‘Wonderland’ of the human brain. This flimsy fiction fuels five chapters exploring key aspects of neuroscience. ‘Morphology’ introduces neurons – nerve cells controlling the body, and on which are written “everything you feel, remember or dream”. ‘Pharmacology’ (‘the science of drugs or medicine’), introduces the importance of chemical communication across synapses (junctions between neurons). ‘Electrophysiology’ explains the complementary role of electrical communication between neurons (pictured, left), crucially enabling rapid reaction to threats. ‘Plasticity’ focusses on how memories are recorded, and, lastly, ‘Synchronicity’ considers what are commonly called ‘brainwaves’. It’s a logical approach, though chapter subtitles defining the headline terms would have improved accessibility.

Most of the text is in the form of dialogues between the unnamed everyman and the pioneers of neuroscience. It’s an educational method dating back at least to Socrates, and still effective here. Nevertheless, the subject matter is intrinsically demanding. Understanding neurons may take some concentration, and synapses (junctions between them) even more so. With chapters typically building on the lessons of the last, the book becomes progressively more challenging. Details like how signals move from an axon of one neuron to the dendrite of another, may test readers’ interest. The access character stuck in a brain and quizzing on-site neuroscientists is a sound idea, but would have been more powerful if he also brought a high stakes neurological condition needing diagnosed and treated.

The science is generally engaging to the extent that the authors connect it with humanities subjects, like philosophy and psychology. For example, Pavlov’s famous experiment with dogs (ringing a bell at feeding time, so conditioning them to salivate at the sound), is an effective hook to explain how memories are recorded in the brain. At other times they bring the neuroscience into everyday life. For example explaining the effects on neurons of drugs: from those produced by our bodies like ‘mood regulator’ Dopamine, to recreational drugs like alcohol. While the difficulty increases throughout, this is balanced by increasingly engaging angles. The relationship between brain and mind, will likely engage more readers than ‘the parts of a neuron’. So is this book ultimately a good way to explain neuroscience? Sources like the BBC’s education pages offer clear definitions, but Neurocomic more vividly orchestrates what the authors poetically call “the symphony of the brain”.

The art is well-pitched between cartoon and diagram, and the best pages are as appealing as they are informative. Heads are perhaps too large for bodies, but that’s in a long cartooning tradition, optimising both facial and bodily expression in limited space. Attentive readers will manage to differentiate the numerous men in suits through subtle sartorial details like haircuts, shirts, and open or closed jackets. However the strongest visuals are not the scientists but the science: anthropomorphised ions, a forest of neurons, and a sea of squid-like synapses. Out of context, some imagery may seem reductive or patronising, but it’s a sound way of making complex concepts relatable.

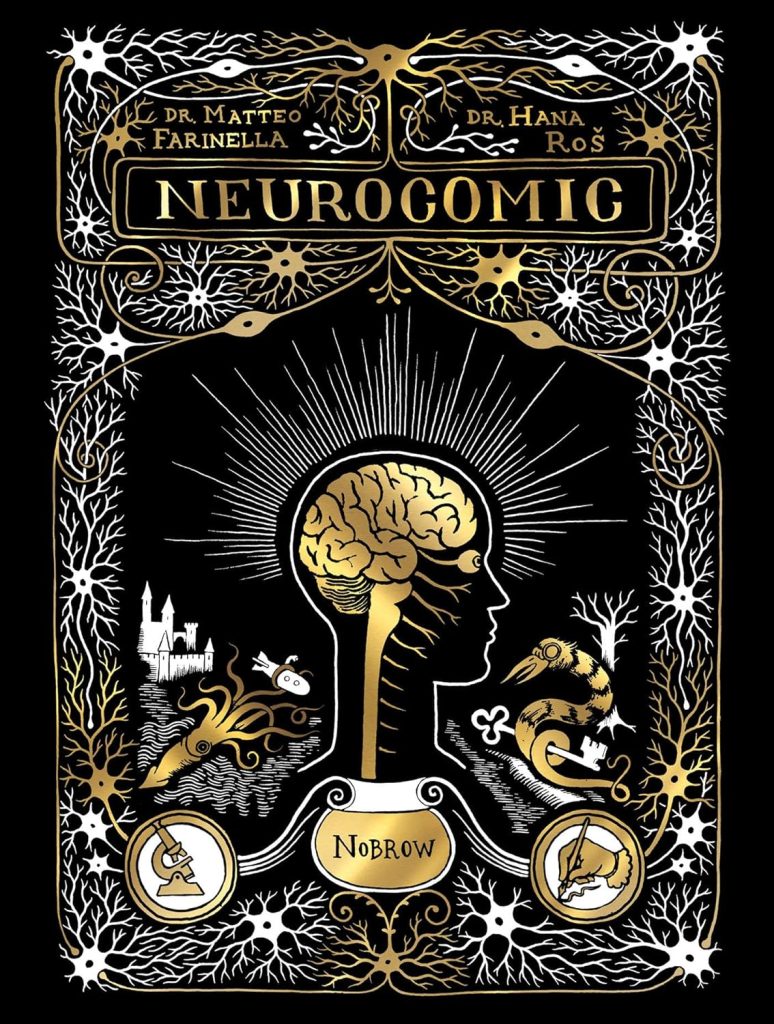

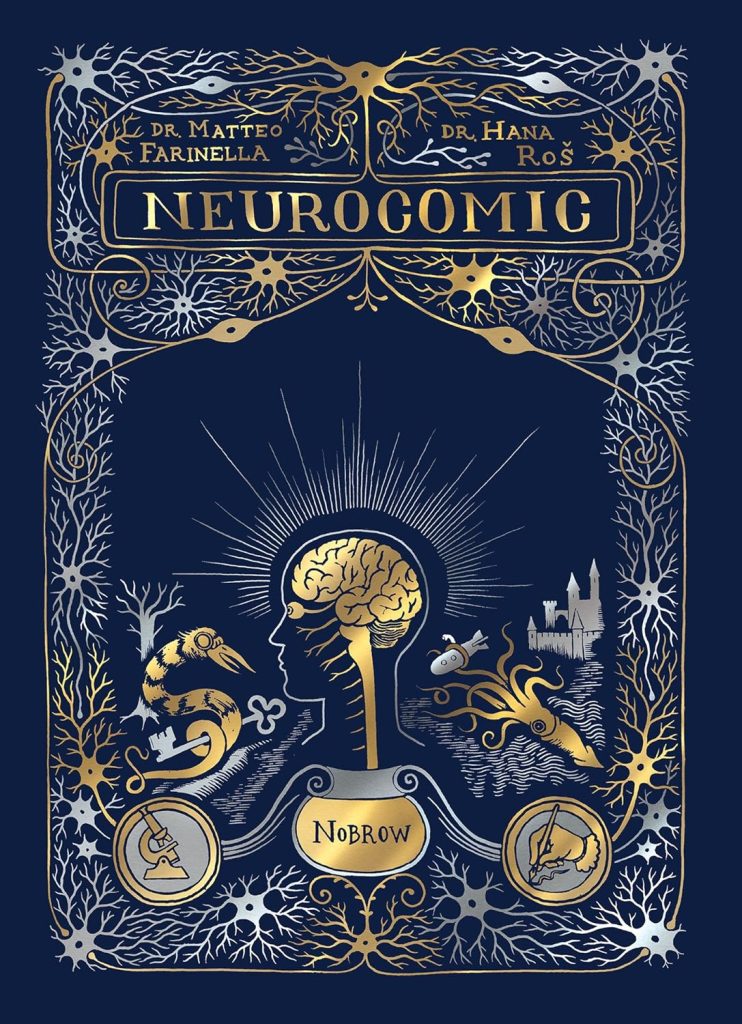

The silver and gold printing of the cover (paperback and hardback variants pictured), exemplifies British publisher NoBrow’s design and production standards. The style is similar for Farinella’s follow-up, The Senses.