Review by Frank Plowright

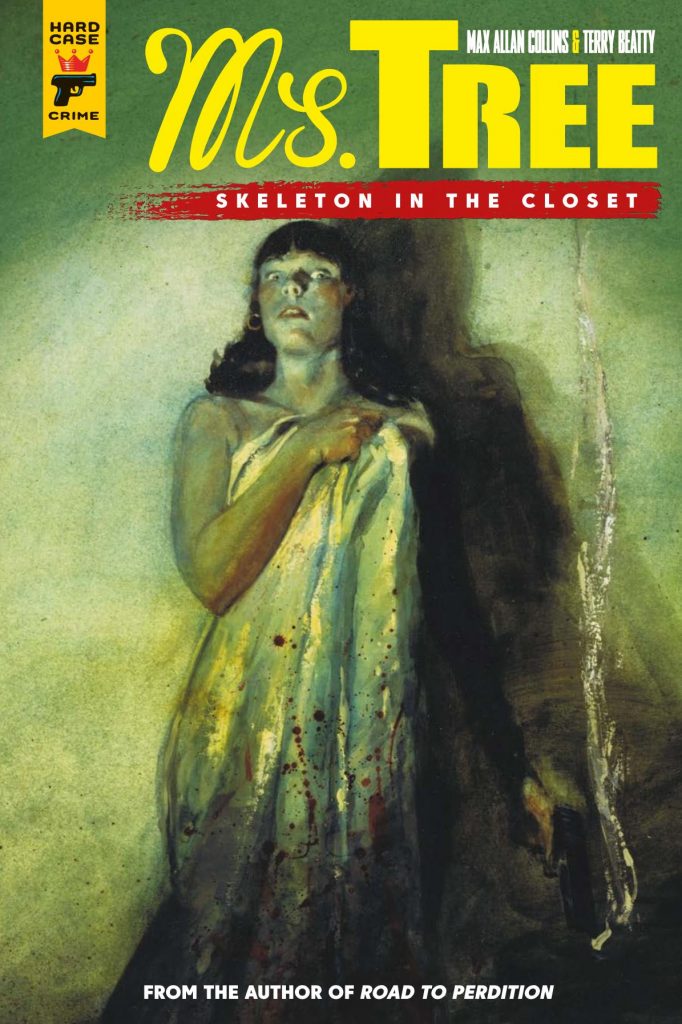

It may seem that Max Allan Collins’ introduction to Skeletons in the Closet supplies spoilers about the six stories that follow, but they’re only superficial, revealing events that occur early. The disclosures are made in support of explanations about contemporary headlines influencing his storytelling, and how he was able to treat matters in a more adult way in Ms. Tree than when writing the Dick Tracy newspaper strip. While threads connected the five stories in One Mean Mother, beyond the recurring supporting cast these can all be read independently, and as a selection, removing much personal content means they’re weighed more toward the detective heading from clue to clue.

The topics spotlighted are satanic churches, homophobia, college murder and rape, and missing Vietnam vets, and some brave storytelling choices are made. As noted in Collins’ introduction, the violent anti-gay bigot is a long term supporting character, not just a random introduction for that purpose. There’s sometimes too much shorthand, but Collins doesn’t advocate any single view, and the people who could be seen as being right are as likely to be wrong’uns in other ways. Ms. Tree herself provides an example of that, being very much in favour of dispensing her own justice. When the issues were more personal there was a slim justification for killing when other options were available, but here she’s almost the Punisher in her judgements. Some context is provided by the reprinting of a mid-1980s story in which possible mental health problems are addressed, although there’s less subtlety about this outing.

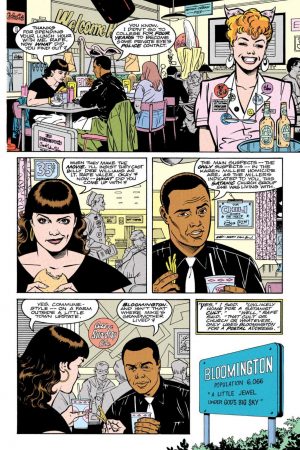

As his best, artist Terry Beatty charms with detailed and busy backgrounds enlivening conversations and the well-defined people, but there’s a posed stiffness when people need to move, and expressions are too often oversold in tense moments. However, the storytelling is the personification of clarity. There’s never any doubt as to what’s happening, nor where the eye needs to be led.

One story departs from the headlines, as Collins and Beatty indulge in a love of horror, mixing both the criminal and possible supernatural forms along with plenty of homages in a romp that’s a needed change of tone from the heavy subjects of the companion tales. It’s certainly adult and sordid, as an entrepreneur exploits the reputation of a mansion house where crimes have occurred by converting it into a themed hotel. Ms. Tree is hired for the launch as one of seven people who’ll spend a night in the place before it opens to the public. The general direction is predictable, but it’s more obviously fun than the remaining content and comes with a good twist.

The stories have been resequenced from the earlier publication, so one element of the final story will be a jaw-dropper for anyone who’s not read One Mean Mother. That also features one hell of a convenient coincidence, and the ending is only ever heading one way once the big revelation has been made, but otherwise the idea of Ms. Tree away from her comfort zone and having to trust others is sufficiently novel.

Seasoned mystery readers may have instincts about the way some stories go, but Collins will generally surprise, which makes this another worthwhile collection. It’s rounded off with another prose story, this time an Edgar Award winner for Best Short Story.