Review by Graham Johnstone

This twelfth volume marked three years of Fantagraphics paperback anthology Mome. It’s seen a gradual shift from the ‘literary’ bias of the earlier issues: slice of life stories, and generally naturalistic rendering; towards more visually led work, and sequential art that’s almost defiantly un-literary. Regulars have also made way for newcomers, with no less than five debuting in this volume alone.

Olivier Schrauwen’s debut is ‘Hair Types’ – an exercise in archaic pseudoscience as sepia tinted men attempt to deduce personality from hair type. One sequence progresses from a picture of a man’s “crazy” hair to a diagram of supposedly corresponding personality traits such as laziness, and aggression. Then we see these traits personified as figures in a scene, and then forcefully enacting their sole characteristic in relation to each other. There’s sharp wit and visual ingenuity in search of a worthy narrative: he’d later find it in the memoirs of his grandfather Arsene Schrauwen.

Fellow debutant Sara-Edward Corbett has an elegant clean style with a touch of Picasso. She incorporates the narrative of Treasure Island into her story of class-room dynamics, specifically through it’s iconic warning of death. It’s all good fun, but there’s a darker look at childhood in Patrice Killoffer’s ‘Dirty Family Laundry’. It turns from scatological indulgence to an impressively frank, forensic, and apparently autobiographical, account of a difficult childhood. He has an abstracted style, also reminiscent of Picasso – right down to his mother’s multiple eyes looking in all directions – suggestive here of inner conflicts.

Pieces by Al Columbia and Derek van Geison are entirely wordless. The former is beautiful but minimal – some cats patrolling a town. The latter’s style could be mistaken for Edmund Baudoin as the fashions and buildings also pass for his timeless Paris. It’s beautifully rendered in some of the most loose, expressive brushwork seen in the medium, particularly a frameless sequence of a woman dancing: a silhouette of slender limbs and billowing dress. The narrative is dream-like, yet gently raising issues about the relationship between humans and animals.

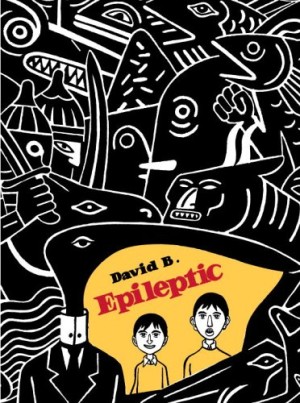

David B. (sample page) adds to the visual brilliance a compelling and well realised narrative in his stunning, ‘The Drum Who Fell in Love’. It’s now available in The Armed Garden, together with his two companion pieces from Mome. Fantagraphics also went on to collect Tom Kaczynski’s contributions as Beta-Testing the Apocalypse, his one-pagers here adding to a tight thematic whole.

Sophie Crumb opens and closes the book with short pieces in polar opposite styles, yet both look at women in America’s past. She’s surely the only person to have done a remake of a 1930’s Tijuana Bible. These were generally dismissed as pornography, and rarely admired for narrative finesse. Still, as adapted here it addresses not just male desire, but that of young and not-so-young women. As the child of a famously liberated mother, maybe this supposedly ‘found’ narrative has another layer.

Though printed in full colour, most stories are restricted to a palette of warm, autumnal colours. It mostly works. David B adds simple but effective sepia washes. Columbia, with his typical blend of perversity and visual panache, makes the cats roaming his sepia scenes a contrasting blue. On Ray Fenwick’s ‘Truth Bear’ though, the orange overlay sits heavily his delicate lines, and the ‘mustard selection’ coloured pencilling distracts from Nate Neal’s virtual anthology of intriguing short and tiny pieces.

The shift in editorial policy from literary fiction to more visual and less narrative material was a bold and laudable one. The contents mostly satisfy, and it’s hard to point to anything unworthy of inclusion.