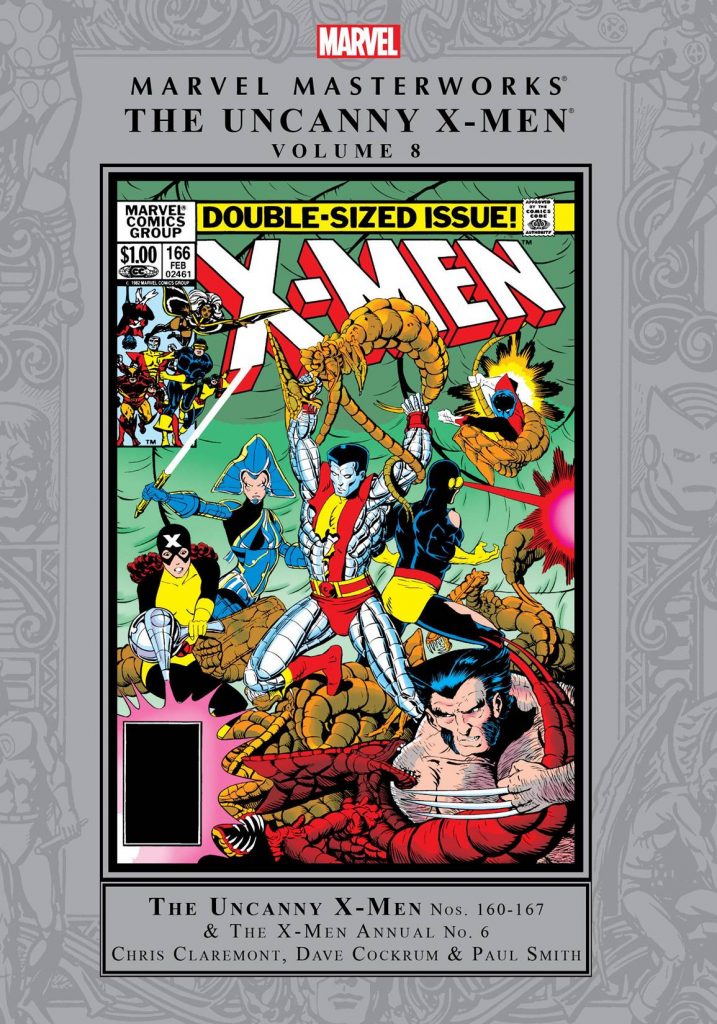

Review by Frank Plowright

In her introduction Louise Simonson, who edited these stories in the 1980s, draws attention to writer Chris Claremont’s frequent use of transformation as a theme, and one of his most dramatic examples occurs in the opener. It also continues his policy of consistently transforming the milieu applying to the X-Men, sending them to Limbo, controlled by the demon Belasco, where present and future co-exist, and investigating duality. It’s an interesting premise with an interesting outcome, but not a very interesting story. While the genre differs each time, three of the first four episodes use illusion or hallucination as a device, a repetition shown up by their collection, which Claremont couldn’t have foreseen when he wrote for monthly publication.

An extended trip into space was a key sequence in Vol. 7, when the X-Men thought a battle had been won, although at a cost, but were unaware of machinations behind the scenes. These now come home to roost as the team head into space again, discovering who the Brood are and how they survive. Simonson can’t say so in the introduction, and neither can Claremont in-story, but his Brood aren’t too far removed from the cinema Aliens, to which he adds a culture and motivation.

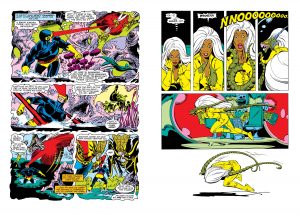

The first half of the collection presents Dave Cockrum’s final X-Men work. The new team’s co-creator hadn’t felt able to step up to monthly deadlines in 1978, and the layouts produced after his 1982 return rarely matched the expansive nature of his pages from several years earlier. It’s only partially explained by Claremont’s plots having a greater density and his word count increasing, as subsequent pencil artist Paul Smith takes similar scripts and avoids the cast being hemmed in all the time. His closing chapters of the space plot have a dynamism missing from those Cockrum lays out and Bob Wiacek finishes, and he gives a visual wonder to inspirational ideas such as the Brood’s craft.

Designed as an epic, the Brood story drags in places, points over-emphasised, yet while the inspiration may be obvious, Claremont introduced the first major alien race to the Marvel universe not humanoid visually or in savage and single-minded outlook. He adds a second race also, even more interesting, and while a good threat hanging over the X-Men needs extending for maximum dramatic impact, the inevitable solution is too easy. Claremont compensates with something better when the X-Men return home, leaving one final alien to be dealt with, and a smart touch is that they’ve been away so long everyone’s presumed them dead, not least the new students. Transformation is again key.

A few short pieces at the end account for the other creators credited, the best of them Wolverine meeting Hercules by Mary Jo Duffy and George Pérez inks swamping Ken Landgraf’s pencils. Before then Claremont reprises the gothic horror of Dracula’s appearance in the previous collection. It’s again efficiently drawn by Bill Sienkiewicz, then still shaking off his Neal Adams influence rather than using his later wilder style, and incorporating innovative designs, although the layouts become more ordinary as the story continues. Claremont minimises the unconvincing infatuations of the previous vampire story, instead opting for a horror thriller, but it’s not his finest hour and Tomb of Dracula fans won’t be pleased at his transformation for one of the supporting cast.

With this and the previous volume, Claremont’s X-Men slightly hit the doldrums, but Vol. 9 is a stunning return to form. Can Vol. 10 be as good? These stories are alternatively available in black and white as Essential X-Men Vol. 4. or in the third Uncanny X-Men Omnibus.