Review by Karl Verhoven

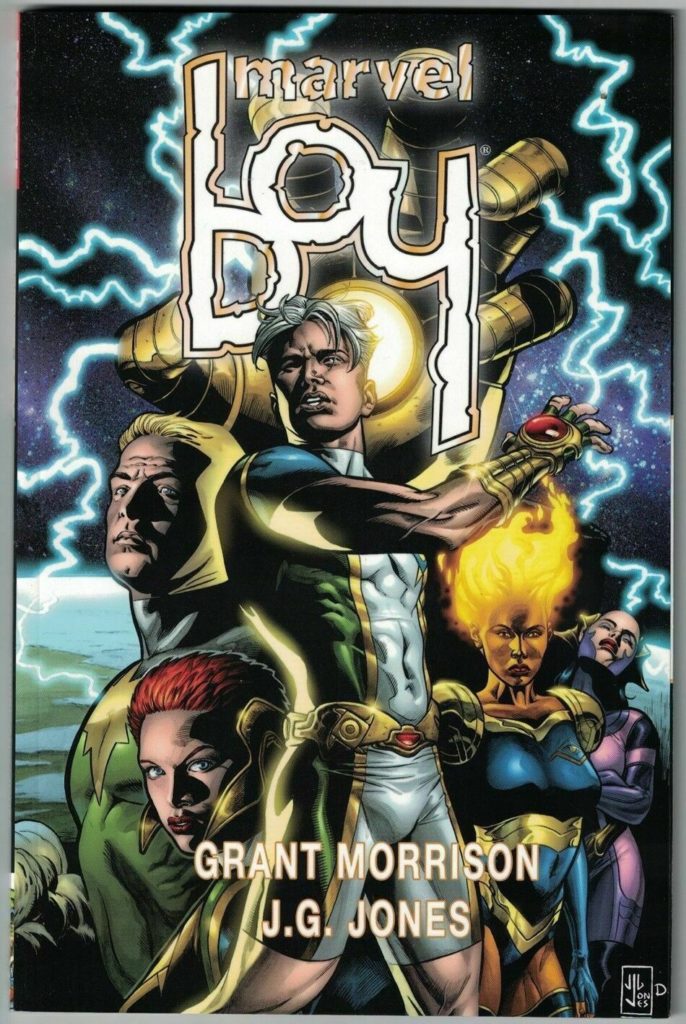

Since the original serialisation in 2000, Marvel Boy has been a sustained success for Grant Morrison and J.G. Jones. It’s rarely, if ever, been out of print in twenty years, and has even graduated to hardback editions. It’s a contradictory piece, indicated by the title character never once using the Marvel Boy name, dense with ideas and having a Formula One injection of pace from start to finish.

For reasons that become apparent very early, Morrision sets Marvel Boy in an alternate universe. The young Kree warrior Noh-Varr is the only survivor of a craft finding its way back home when targeted by an energy beam from Earth, and he’s captured while the wreckage is sifted for technology. While the ship can eventually repair itself, the damage has let some dangers loose, well beyond human capability: “The living corporation is a ferocious parasite adapting quickly to the needs of its target world”, explains Morrison via Noh-Varr’s computer, the CEO later helpfully adding “We will licence the air you breathe and the thoughts we allow you to think”. Satirical comment is part of the Marvel Boy package, as is the twisting of the familiar, such as the villain of the piece strolling around in a clunky gold Iron Man suit. The self-awareness is off the scale, as Morrison throws in state deception, a sordid father/daughter relationship, a scathing interpretation of humanity’s administration, knowing dialogue throughout, an incredibly pompous villain and a hatred of corporate culture. That self-awareness extends to Morrison placing Marvel Boy among the late 20th century superhero reconstructions of Warren Ellis for a panel, before a sequence in effect declaring the Fantastic Four redundant. Let it be said that was around fifteen years before Marvel did the same.

A more palatable veneer is supplied by the first rate superhero art of J. G. Jones, whose character subtlety presents the necessary nuances of a powerful, yet ultimately conflicted being, following learned patterns, yet only really successful when breaking free from conditioning. Jones implants Noh-Varr in sufficiently strange surroundings when on home territory, and emphasises the familiar away from it, always pouring in the detail, including pages where he seems to have turned to Jim Steranko for inspiration. Steranko was always the most modern of superhero artists.

It has to be asked whether Marvel Boy is too smart for its own good. It is. The technobabble is likely to put off as many people as it intrigues, and how many people really want to peel back layer after layer in a basic superhero story? On the other hand, it’s clever, witty and the ground constantly shifts, and that’s why it’s still in print. What isn’t is the intended follow-up, which was never produced. Instead Noh-Varr slid across to the main Marvel Earth to be co-opted by the Avengers.

For an interesting in-depth speculative analysis of what Marvel Boy may represent, check Chad Nevitt’s blog.