Review by Frank Plowright

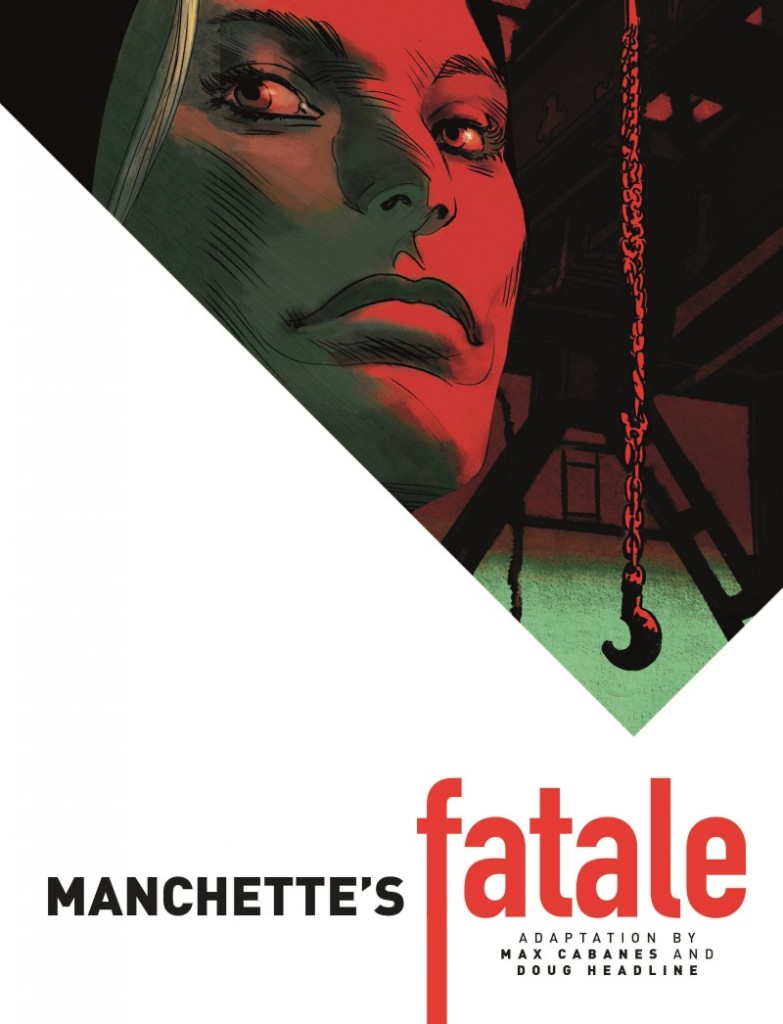

It might be assumed that Titan adding Manchette’s name to what was originally Fatale in France avoids confusion with Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips’ English language Fatale, with which it shares only mood and title. The reasons, however, run deeper.

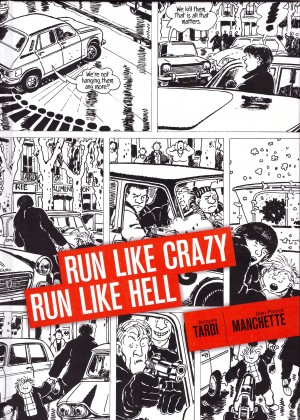

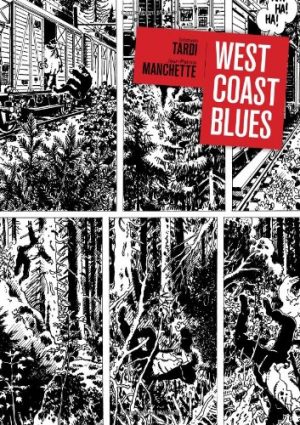

Until 2015 Jacques Tardi had a monopoly on adapting the pulp crime thrillers of Jean-Patrick Manchette for graphic novels, doing a fine job (see recommended reading), but Fatale was a more experimental novel, differing from the pulp thrills of Manchette’s other work. Tardi actually began an adaptation, but discarded it, unsatisfied, leaving the field clear for Doug Headline and Max Cabanes.

We observe a woman who calls herself Aimée Joubert as she in turn observes the upper social class of a small industrial French town in the mid-1970s. We’ve already seen her kill a man with little thought about the deed. She’s not the sole observer of these civic leaders and their wives, as in the mid-1970s plenty of successful people had concealed their activities under German occupation during World War II. The wildly eccentric Baron Jules is the author’s contemptuous voice when contemplating the vacuous concerns of the town’s elite, but he’s been watching them for forty years and has evidence of their past deeds.

It’s typical of Manchette that the specifics of the bomb setting his plot into high gear remain unknown. Joubert explicitly states she doesn’t want to know, and it reflects the opening murder where the motive remains elusive beyond money being mentioned as a constant requirement. This is accentuated in a very eccentric subsequent scene featuring ritual masturbation using banknotes with sauerkraut and champagne as essential accompaniments to the aftermath of killing. We never entirely learn why she kills, although she mentions beginning with her husband.

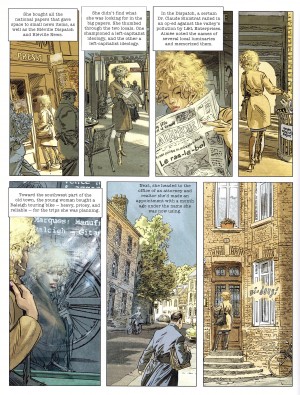

Although credited as Headline, the adaptation is broken down by Tristan Jean Manchette, son of the original author and a writer and documentary film-maker in his own right. It’s a reverential work, with Headline using as much of his father’s original text as possible, and Edward Gauvin’s translation accurately transferring the deliberate phrasing of that text. The sample page has some clever word play defining the town newspapers, for instance. The all-important characterisation is visually conveyed by Max Cabanes, who designs a diverse cast who can be distinguished, which is important as Joubert’s machinations encompass a dozen citizens. He likewise creates an authentic small town, and drapes his cast in shadows to reflect the noir plot.

While some alternative colour choices on the part of Cabanes might have been more effective, the problems with Manchette’s Fatale are down to the original text. It’s weaker than the character studies adapted by Tardi, recognised by Manchette’s publishers who wouldn’t include it in their crime line. A primary failing is that Joubert is never fully revealed (discounting the contrary scenes of nudity), so there’s no emotional attachment to her, making her story more a documentation than a novel. Her odd relationship with the contrary nonsense-spouting Baron Jules makes little sense until she needs him, and Joubert’s passivity is strange, then shed for no particular reason to deliver a scathing indictment of a companion. While the plot ties together impeccably, the structure is odd for a novel, resembling a three act play with prologue and epilogue, and more than any other of Manchette’s crime-based works Fatale seethes with a contempt for not only hypocrisy, but achievement.

At face value meticulous planning leads to a tense action finale occupying over a quarter of the book, so Manchette’s Fatale is a good read, but a flawed one.