Review by Ian Keogh

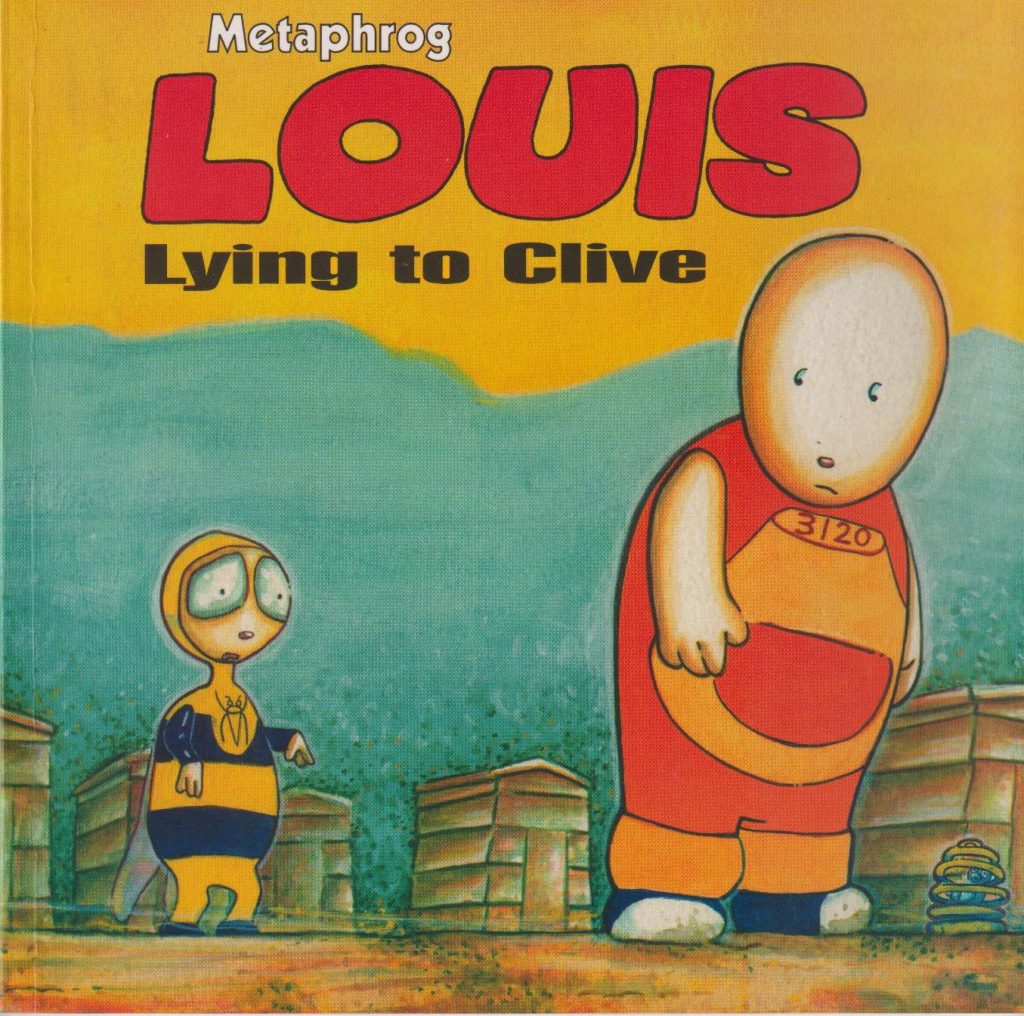

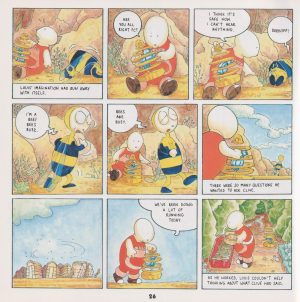

Louis has been sent to work on the Bee Farm. This has nothing to do with cultivating bees, but is known as such for all workers being dressed in bee costumes and living in small, hive-like structures. Their actual task is to mine a substance called monetarium, and Louis is there for damaging public property, the deed seen in Red Letter Day. He’s befriended by the addled Clive.

To a greater or lesser extent all Louis books are some form of social commentary, but the allegories aren’t always clear. Lying to Clive is the most transparent of the series, considering the soul-destroying conditions of workplaces, the lack of awareness or care about mental illness and how society is stacked against the poor. As in other books, Louis is resolutely good natured, despite his optimism occasionally taking a dent, and is unable to comprehend why he’s being treated so poorly.

Unlike other Louis books, Lying to Clive can’t entirely be understood without reference to Red Letter Day. There’s no explanation of the neighbours who torment Louis, seen conniving in his absence, and receiving letters Louis sends to his Aunt Alison, who doesn’t exist. She’s their creation.

The neighbours and the general sense of oppression represent the bleakness characterising a melancholy experience belied by the cheerful simplicity of the drawing. Although seeming to be a book aimed at children, children are more likely to be disturbed than entertained by the sinister circumstances, especially the final scene. Despite the suggestion of the title, by the way, it’s not Louis who’s lying to Clive.

Louis isn’t a series for everyone. There’s a cultivated dreamlike quality as Louis drifts through strange and disturbing events, yet the abstractions and arbitrary nature of what happens will put off anyone looking for logic and reason. Accept it as a jazz improvisation around them, though, and Louis may appeal. If so, The Clown’s Last Words is next.