Review by Frank Plowright

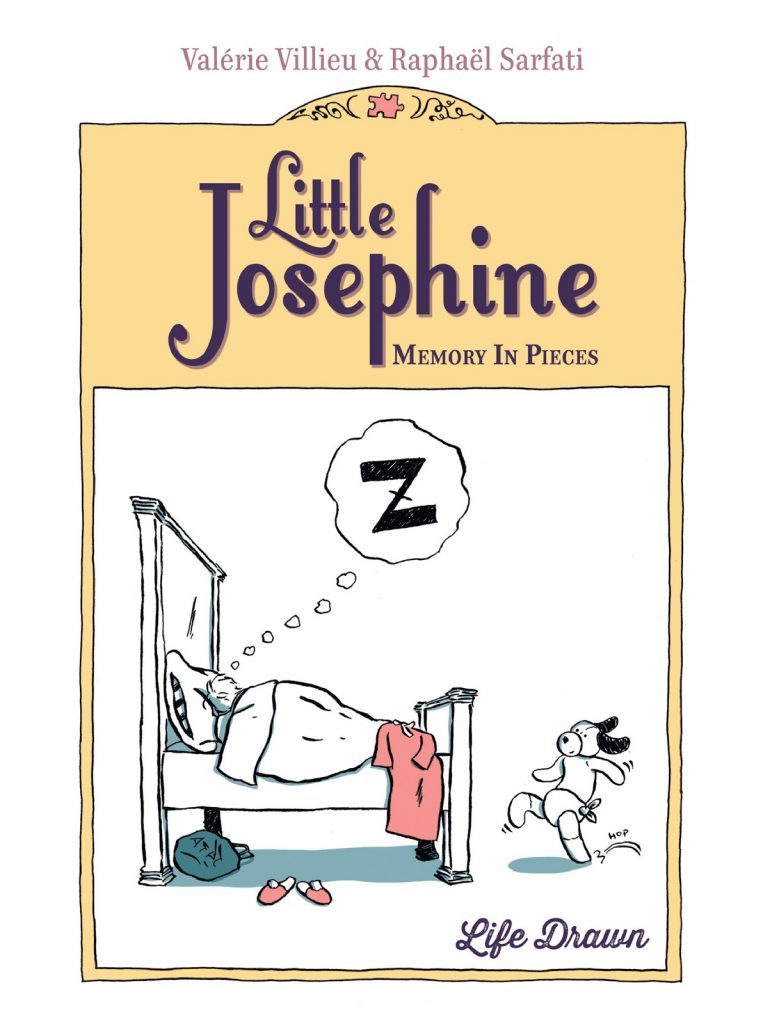

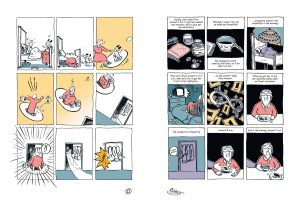

As seen by the sample art, there’s a confusing start to Little Josephine, but it’s more indicative of the subtitle, Memory in Pieces, representing Josephine’s state of mind as imagined by the creative team. Valérie Villieu is a nurse based in Paris supplying home care to those unable to look after themselves. Officially her duties in Josephine’s case are to monitor any decline and administer necessary medicine, while separate caregivers are tasked with providing meals and other daily tasks.

Josephine has spent almost her entire life in a small apartment in the same neighbourhood where she grew up, and where her parents ran a bakery. By the time Valérie becomes involved the capable person Josephine once was has long disappeared, eroded by Alzheimer’s Disease. She takes great coaxing just to carry out simple daily tasks, but the story is one of heartwarming wonder as Josephine is rounded as a human being, not the just the dotty old woman most people would see.

Switching moods between the different ways life is perceived requires a talented artist and Raphaël Sarfati’s very strong on both the real world and the strange one of daily struggle, channelling either discipline or imagination. It’s an appealing combination, and Sartafi’s layouts for the real world highlight the subtle touches such as the meal not being eaten on the sample art. Whether Villieu’s suggestions or Sartafi’s interpretations, visual metaphors are creative and thoughtful, and occasionally photographs defining Josephine’s past are factored into the pages.

In addition to noting her day to day relationship with Josephine, Villieu reveals how social workers in France are just as overloaded as those in the UK, their heavy caseloads preventing them helping anyone effectively unless they choose to prioritise one person over another. She’s especially caustic about the caregivers who have time to carry out their duties and offer greater help besides, yet don’t bother. This broadens into wider social problems experienced by the one decent caregiver, who’s Ivorian, and a trained accountant who can only find work looking after the elderly, frequently experiencing racism.

Villieu’s career experience makes her an incisive interpreter. The abiding message is that of respect, involving small touches like accepting that what may seem rubbish to one person is treasured by another. We actually learn very little of Josephine’s life as it was, but come to know the fears and routines of the woman she was in old age. We know there’s going to be no happy ending, that Alzheimer’s Disease is progressive and final, yet Villieu’s heartfelt concern transmits, ensuring small victories are shared and reinforcing should it be necessary that dignity ought to be a human right.