Review by Ian Keogh

The small print at the front of a book is generally of greater interest to librarians and cataloguers than readers, but don’t miss the eight lines noting the publication history opening Life of Che. It contextualises the dangers of two Argentinian creators living under a right wing military dictatorship in the late 1960s celebrating the life of a left-wing revolutionary.

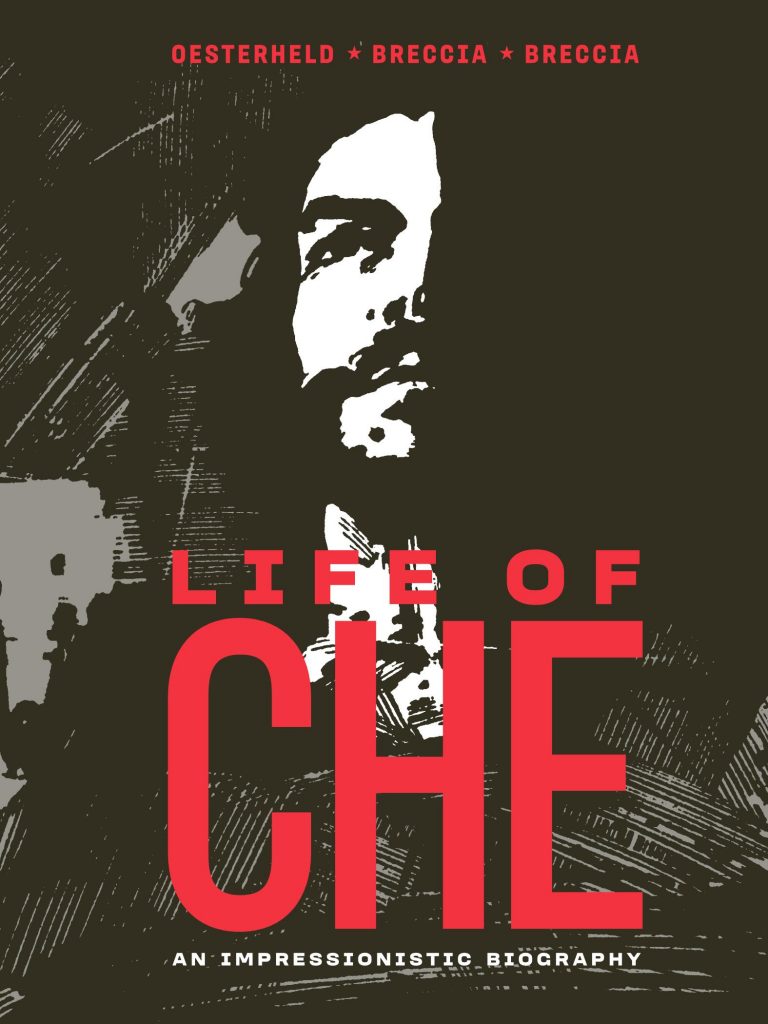

Outside Central and South America, history has largely reduced Ernesto “Che” Guevara to an iconic t-shirt design, diminishing his status as an important force for change, most lastingly in Cuba. The commercialisation of his image was at first a means of keeping his spirit alive, which was the same approach Héctor Oesterheld and Alberto Breccia took in 1968, the year after Guevara’s death. As with his image, much of Guevara’s life has been mythologised over the years, and a strength Life of Che has is that it’s stripped back from much of the baggage.

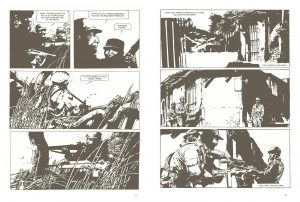

Even reproduced from smudgy third-hand sources (all that’s available), the art is remarkable, all the more so for the project being a passion for Oesterheld, but according to the informative background essay from Professor Pablo Turnes, just another job for Breccia. Nevertheless, Breccia can’t ever be anything other than a thoughtful illustrator and even muddied portraits shine, while there’s considerable experimentation, not least the novelty of the final pages resembling a film reel passing before the eyes. He collaborates with his son Enrique, who handles imagined sections set in Bolivia during the final days of Guevara’s life (sample art left) while the more traditional biographical stopovers are handled by Alberto (sample right). Both use woodcuts for some art, a method Alberto would later work with more extensively, with collage another artistic weapon.

Guevara’s greatest success was his part in overthrowing the Cuban dictatorship in the company of Fidel Castro, yet Oesterheld produces a restless Che. He’s disciplined enough to run the Cuban national bank and run it well, but also convinced his best use is via direct action, and it’s eventually his downfall.

Oesterheld’s script veers between Guevara’s first person dialogue and a third person commentary, often covering assorted events in a single paragraph. It’s clipped, wide-ranging, and asks big questions in small blocks, sweeping over the global politics of the mid 20th century, which is interesting, but without concessions, true to the impressionism of the subtitle. For all the artistic innovation and thought behind the script, the success of any biography ultimately rests on how well it illuminates the subject, and by that score Life of Che remains a curiosity rather than a triumph. Oesterheld honestly refers to his being an impressionistic biography, and as such it conveys the thoughts of an intellectual writer applied to a life story. His picture is of a dedicated man for whom the world falls short, and at times that appears to apply to humanity. It’s a story that practically demands greater investigation, perhaps inevitable when the world has moved on considerably from circumstances familiar to the readers at whom Life of Che was aimed in 1968.