Review by Ian Keogh

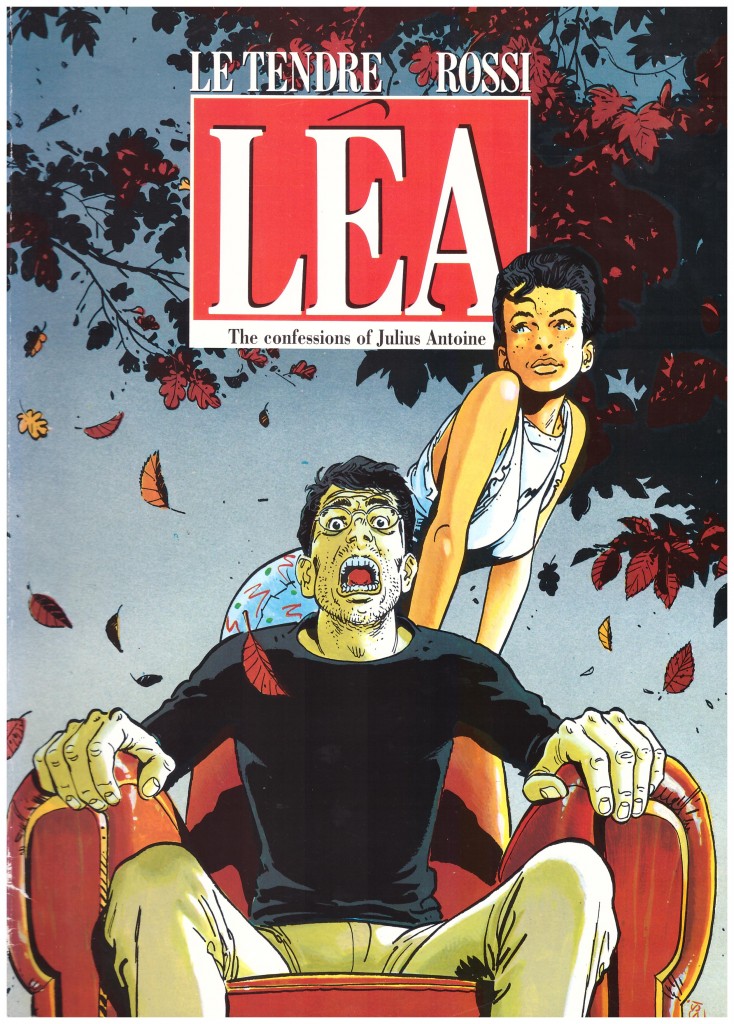

Lea was a very early attempt at introducing European style album graphic novels aimed at adults to an English speaking audience. It’s a sweaty and sordid piece rendered even more atmospherically uncomfortable by shifting moral attitudes.

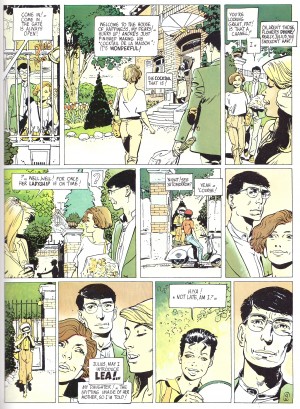

We’re introduced to Julius Antoine on the opening page as he sits in the town square sketching teenage girls in their skimpy summer wear. When his girlfriend Clemence remarks on this, instead of playfully laughing it off he becomes flustered and annoyed. Lea appears soon thereafter, fifteen, precocious and able to push her mother’s buttons effortlessly. The initial shock of the story in fact isn’t the simmering topic, but the casual violence meted out as punishment. Soon, however, we’re privy to Julius’ inner thoughts, and there is a Humbert and Lolita obsession developing. Some clever storytelling on the part of Serge Le Tendre then has Lea’s parents being interviewed by the police, and we learn that’s the present day sequence, and what’s been presented beforehand is the recent past. An element of mystery is preserved, as we’re unsure about what the police complaint concerns as the story moves back to the past.

Le Tendre’s plotting is very clever. The obvious inspiration is the obsessions of Lolita, but there’s a point at which the plots take very different paths, as Lea becomes a crime story, one investigating how certain crimes prompt witch hunts.

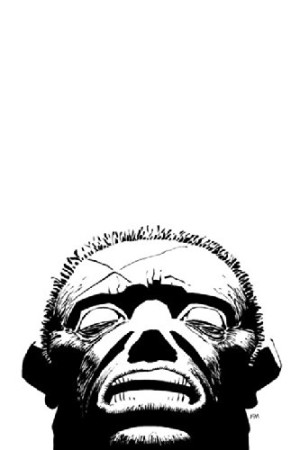

Christian Rossi at that point was just beginning what’s become a long and accomplished career drawing graphic novels, and there’s evidence of the novice artist in both the storytelling and the execution. This, however, is minor in comparison to what Rossi’s already doing very well. He conveys Antoine’s inner torment, the manner in which he attempts to struggle with and repress his natural inclinations, and the rage this induces, but there’s a lightness to his cast when needed. The pages aren’t well served by the colouring, which isn’t separately credited, so presumably Rossi’s work. There’s a muted and shady look that comes across as primitive rather than reflecting the nuances of the story.

The final pages are somewhat over-egged, but not to the point of entirely negating what’s come before, and there’s a conclusion open to very sinister and unpleasant interpretation. Lea is complete in itself, but Julius Antoine’s troubles continued for two further books, never translated into English. They’re easily found in French, but don’t match the shock or simmering undercurrent of this introduction.