Review by Ian Keogh

Laura thought she’d met the ideal guy in Marcos, and from what we’re shown, in many ways he does seem ideal, being considerate, attentive and thoughtful, but just not for Laura. She has a hard time accepting this, and like anyone whose love isn’t reciprocated, she clutches at straws and believes she can transform friendship into something more.

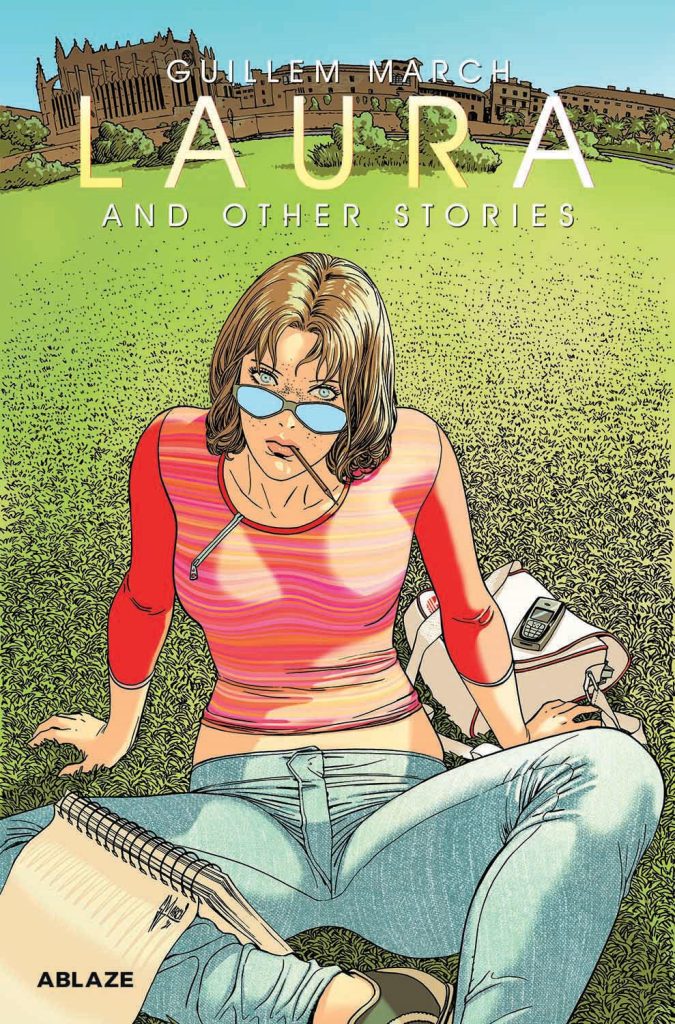

Guillem March serialised ‘Laura’ in his native Spain a few years before starting work on Batman and other US series, and his art is still very much a work in progress here. Some beautiful pages are mixed in with others where the storytelling is awkward and enclosed when some distance would better convey the emotional states carrying the plot.

That plot begins with Laura having to accept Marcos isn’t for her, and moving through the depressive reflection, and attempts to do something, anything, to move her life onward. She hangs out with her far livelier friend Elena, who’s not greatly concerned about not having a man in her life as she can pick one up at any time. Elena initially seems shallow, if nevertheless well intentioned, but there is more to her.

‘Laura’ occupies two-thirds of this collection, and it’s very much an early work from a promising creator. The suspicion is that March is purging some of his own experiences by switching the gender of the leading character, which he does with a later story, and that indicates a personal resonance. However, it’s perhaps too true to life as it lingers on moments that only matter personally and takes too long to tell a relatively simple story. The ending is problematic as well. Laura’s feelings have been thoroughly explored, so the sudden change of heart at the end on the final page doesn’t ring true, despite a form of explanation.

That’s a subject explored in ‘Irene’, in which March initially hides behind the title character and has genius Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki turn up in a World War I fighter plane to shoot down March’s limited creative impulses. Via Miyazaki he’s harsh on the self-doubts that all artists have, and he explains the motivations for that and the other remaining pieces in introductory pages. ‘Muse’ is the best of the book, all the more remarkable for originating as a series of limited edition drawings included in individual copies of a crowdfunded comic. It concerns the reactions of a woman to her male flatmate needing to have a naked model in their home for a life drawing exercise. The panels are delicately drawn and it’s sweet and funny while raising a valid point, if quite blatantly undermining that point by producing ‘Muse’ in the first place.

This is definitely an artist in progress, but accepting that, if you like March’s art now, it’s worth seeing where he came from, right?