Review by Frank Plowright

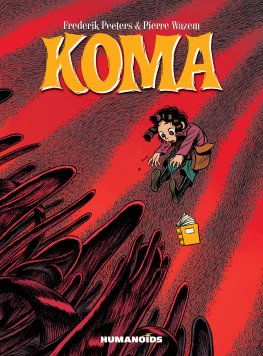

In collecting the original six French-published instalments into a single volume with a hefty 275 story pages, Koma certainly lays claim to both portions of the graphic novel designation, but length alone is no indication of quality, and Koma is remarkable.

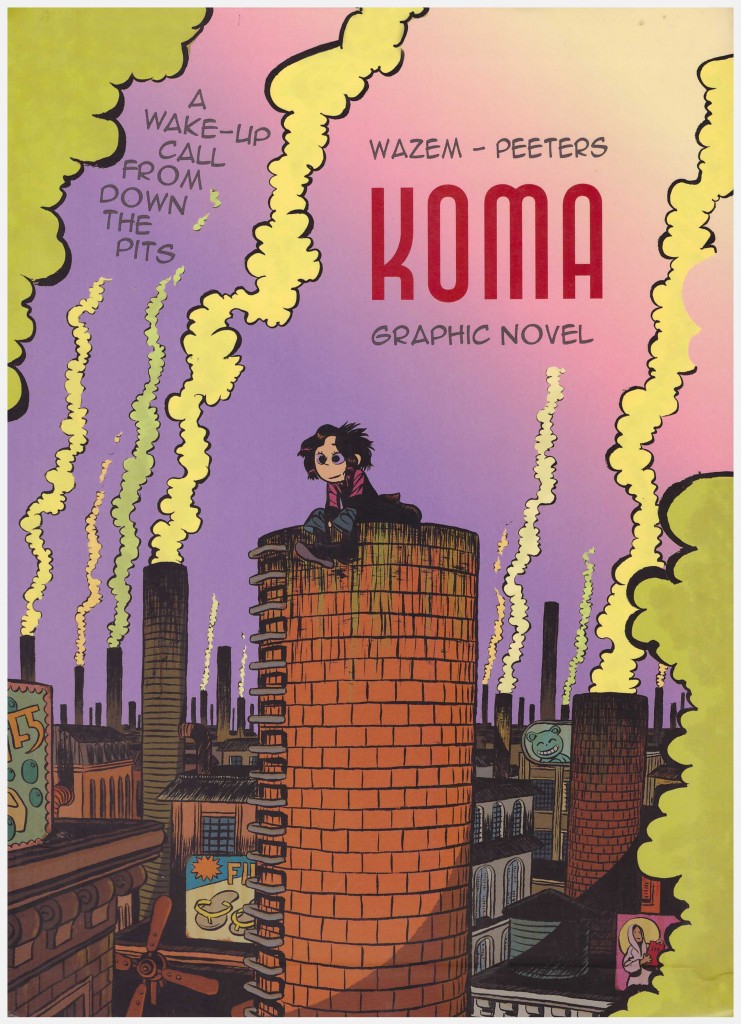

The eccentrically named Addidas accompanies her father on his rounds as a chimney sweep contracted to cleanse the city’s giant smokestacks in a curiously oppressive society, crawling through the thin connecting flues her father cannot traverse. A precocious and sympathetic child, she’s also prone to lapsing into comas attached to no discernible medical condition. Both aspire to visit the countryside, an area that acquires mythical status.

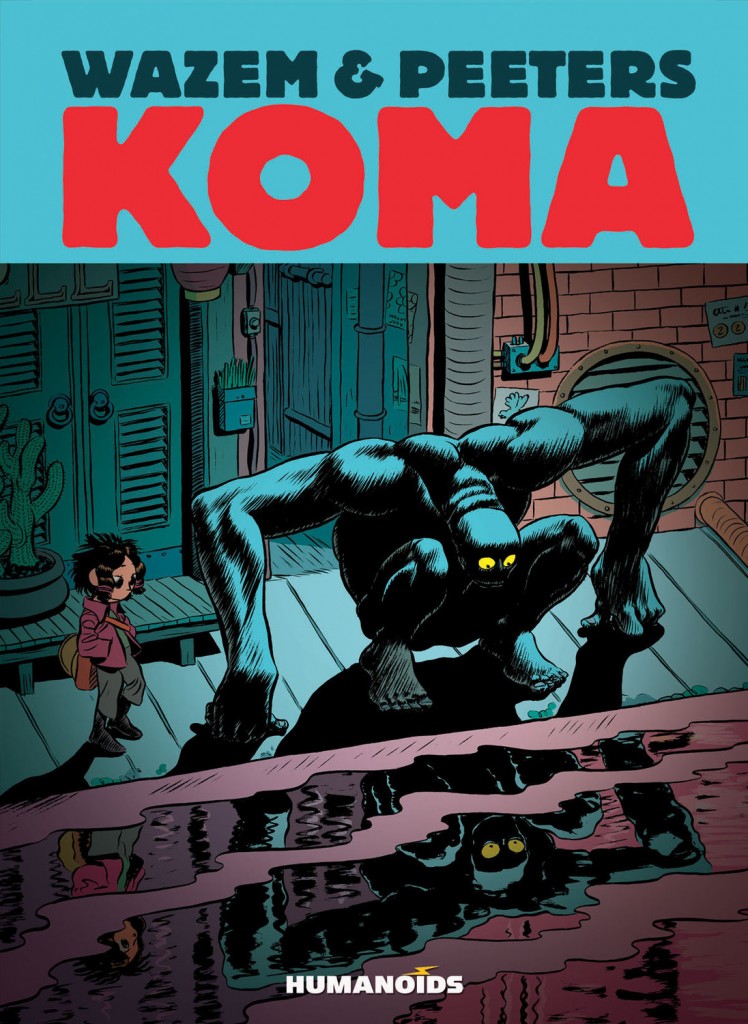

Eventually there’s a job from which Addidas doesn’t return. While her father frantically solicits help from an uncaring police force, she descends ever downward until meeting a blue ape-like creature. She learns he’s one of many tending to complicated machinery, and that each individual machine is connected to a human. When the machine ceases working, the human dies. Oddly, Addidas’ machine has long ceased to function, yet she’s alive.

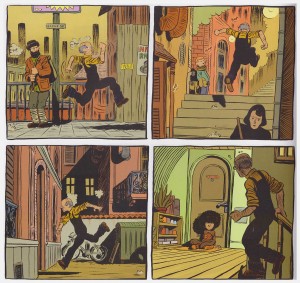

Koma is a collaboration between Swiss creators Pierre Wazem and Frederic Peeters, both previously known for their individual work. Being an artist himself, Wazem’s script is very visual with space for both pause and interpretation, and Peeters’ cast of universally wide-eyed characters populate both a dingy underworld and claustrophobic surface. In this it’s very reminiscent of Christophe Blain’s The Speed Abater.

Although not immediately apparent, Koma is a meditation on the power of stories both as record and illusion, and how they shape reality. It can also be viewed as Wazem’s comment on the succession of boundaries breached as science delves ever deeper into the mysteries of human life. Alongside the main plot a pair of sinister power-hungry bureaucrats have learned about the machinery, and with the prize of eternal life dangled before them their atrocities are boundless. Koma eventually travels to somewhere entirely unpredictable, yet wonderful in context.

It’s a curious decision to market the UK edition as a children’s graphic novel, perhaps designated so by the fallacy that any story in which a child is the main character must be for children. While certainly accessible to children, there is graphic depiction of torture, primarily descriptive, and the underlying premise spirals the story into ever more surreal territory.

Addidas’ inherent optimism, sympathy and generosity prevent Koma from becoming unremittingly bleak, and the creative ambition displayed should be an inspiration.