Review by Karl Verhoven

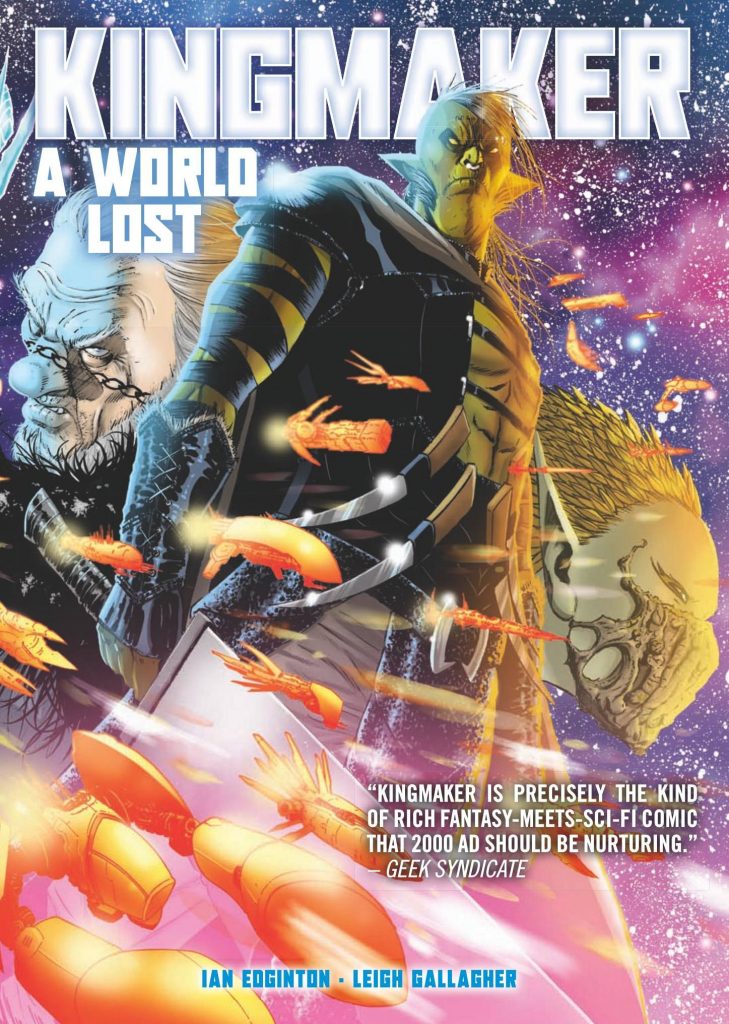

Ian Edginton makes an unconventional start with Kingmaker, the opening pages summarising how Ichnar the Wraith King had let loose his evil on the nine worlds, almost subjugating them until a last desperate battle saved the day. That would generally be the story, and Leigh Gallagher delivers a wild spread showing what happened that day two thousand years previously. Not only does it look amazing, but the people have a later relevance.

It’s been largely peaceful ever since, but more recently a group called the Thorn have begun recruiting thugs, and the Ork Crixus only just prevents some of them abducting a Wizard, Ablard. As per the sample art, he’s aware the magic is being drained from the planet. Orks are apparently not known for their altruism, but with the fate of the world at stake Crixus has no doubt where his loyalties lie. “Like it or not, this is my world too”, he explains, “Why do you find it so hard to reason that I don’t want to see it all end up like this?” Besides, he has cause for optimism, having witnessed an enemy craft destroyed through unknown means, as if the planet was protecting itself.

While not seeming that way at first, in Ablard and Crixus, Edginton is supplying a classic mismatched buddy pairing, respect overcoming prejudice. There’s much to learn about them, and along the way there’s a lecture on judging on appearance, as neither conforms to the first assumptions generated. Gallagher runs with that theme, his visual presentation of who they and others are also shaping opinion. His art is supplied on expansive scale, constructing a world mixing science and magic functionally and decoratively, and the opening spread is far from the only glorious vista supplied.

Space opera and fantasy both revolve around so many expectations it’s sometimes difficult to produce anything greatly original beyond them, yet part of the reason Kingmaker is so enjoyable is the conformity, although that’s far from absolute. Surprises await. One way Edginton differs Kingmaker is that it’s possible to see beyond a rollicking fantasy into a damning statement of any form of colonialism, draining one nation’s resources to enrich another. That incorporates a warning about the greed of corporate culture, and intolerance and racism are constant reactions to Crixus.

By halfway a third member has been added to what’s become a very select band of resistance, and there’s a smidgen of horror and science fiction inserted into a second story that expands somewhere very surprising. In A World Lost Edginton and Gallagher introduce a world of wonder we want to explore further, and give us a hell of a cliffhanger to end. Within the genre boundaries it’s a strong start and looks set for a long run.