Review by Frank Plowright

The story goes that DC attempted to licence Planet of the Apes for comics, but no agreement was reached. With Jack Kirby’s schedule free due to the disappointing cancellation of two titles close to his heart, it was suggested that he create an adventure comic resembling Planet of the Apes. From such an unpromising beginning Kamandi proved not only Kirby’s longest running comic at DC, but a title that survived his departure by two years.

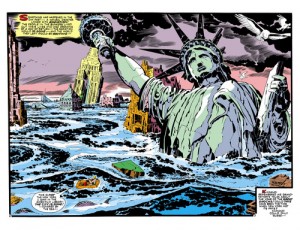

The secret lay in Kirby’s profound creativity. He was incapable of merely copying, so grasped the idea of a subjugated humanity and refused to settle for apes alone, ramping up the concept. In Kamandi’s future all animal species have developed intelligence and near-mindless humans are herded like cattle. The cause is referred to as ‘The Great Disaster’, only ever vaguely referenced in the strips, but in an editorial page Kirby theorised that planetary adjustment, with cataclysmic consequences, was a nature’s reset button. That, though, is only of minimal interest to him as far as his plot’s concerned. It’s dashed off in three introductory captions, which also deliver the explanation that Kamandi’s odd name is a perversion of Command-D, the designation of the safety bunker from which he emerges after the disaster.

Kamandi is Tarzan in a new jungle, but there’s much about him that’s redolent of the serialised adventure strips in British comics of the 1950s and 1960s. He’s a lone hero with no permanent supporting cast wandering from scenario to scenario with no great over-riding mission. These are thrilling worlds of wonder, yet due to Kirby’s intense compulsion to purge ideas they rarely occupy more than a chapter or two. There’s a vague theme of evolution and survival, but that’s secondary to the adventure, as it was in those distant serials.

And what adventure it is. In the first chapter alone Kamandi’s opening encounter with the new world order is greeting a group of humans who flee in fear. That’s followed by a deadly fight with a wolf, a hunter who sees Kamandi as his prey. Kamandi escapes and is shortly in the midst of a battle between tiger cavalry and leopards in feathered hats as if in some bizarre historical recreation outing. He then meets scientist Doctor Canus, and the radioactive Ben Boxer, a human who maintains his intelligence, yet is also a walking atomic pile. It’s a monumental cascade of ideas.

High level excitement is maintained as Kamandi learns how other species have evolved, but the best regarded strip is a change of pace as Kamandi is accompanied by Flower. Rescued from slave traders, she has a greater capacity to communicate than others of her ilk. The pair journey together, evade danger and set up a home in a child’s play-acting manner. It’s very touching. Every bit as good is the moral ambivalence and giant bats of the concluding two-parter.

Kirby’s art is at its 1970s best, inked by Mike Royer. His dynamic, all-action pages deliver an exhilarating read and constant wonders. Beyond the cast there are some stunning landscapes, a ruined Las Vegas, a statuary, and one of his modified photo collages. There’s even a place for an in-joke as Kamandi discovers a copy of Kirby’s then new Demon comic.

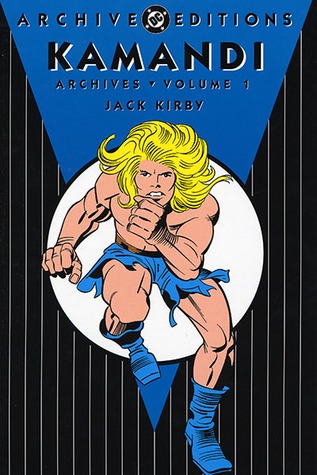

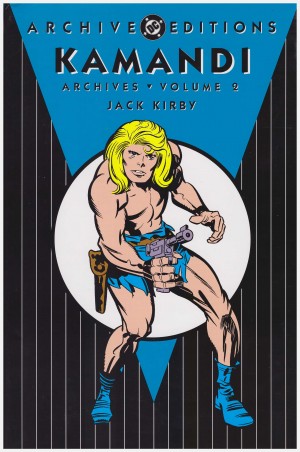

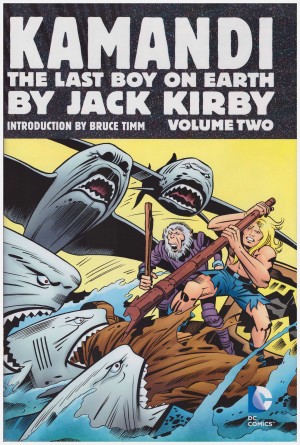

This archive edition is out of print, replaced by a bulky collection encompassing this and volume two or an Omnibus, but on newsprint rather than gloss paper. For the extremely curious (and wealthy) six of these chapters can be found in IDW’s Artist’s Edition of Kamandi, which reprint the art boards at their original size, corrections and all.