Review by Karl Verhoven

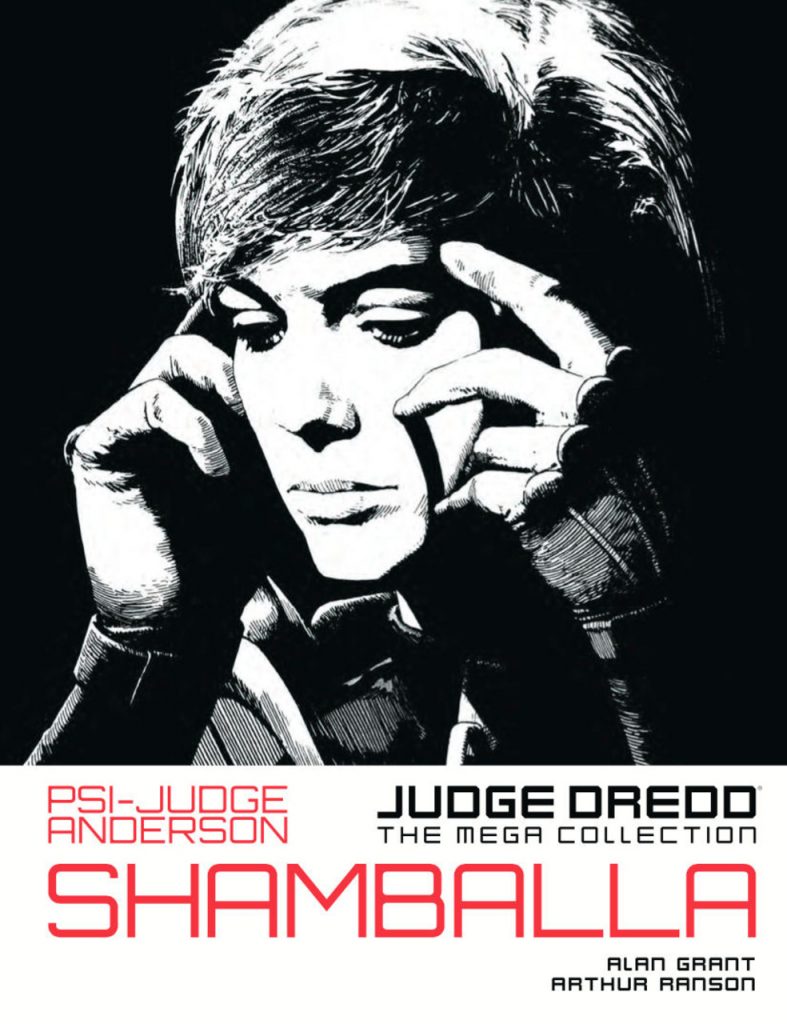

‘Shamballa’ has become Psi Judge Anderson’s signature story, and the best way of experiencing it is in this hardcover collection. True, it sacrifices the album size of the original graphic novel, and even the slightly larger presentation as part of Judge Anderson: The Psi Files Volume 02, but here it’s combined with two further long stories gloriously drawn by Arthur Ranson and two shorts. One is self-contained, with ‘The Jesus Syndrome’ running to three chapters.

Once entrenched as the sole guiding hand, Alan Grant saw Anderson’s experiences as a continual journey, often with spiritual aspects, and everything presented here feeds into that. The title story is the longest, beginning with inexplicable events in Mega-City One, yet by the end Anderson’s experienced love and a considerable awakening as to the possibilities of the universe. She’s always had her doubts about the Judge system in its entirety, but attempts to pass it off with customary bravado. “I don’t believe there’s a race of malignant subterraneans just waiting to invade us”, she tries to convince herself.

It’s a view requiring some reappraisal for the second long story in which the Satan of biblical fame turns up in Mega-City, or at the very least an exceptionally powerful creature believing themselves to be Satan. “I know they say size doesn’t matter, guy”, exclaims Anderson, “but you’re a little overwhelming”. As drawn by Ranson he also possesses the tempter’s confident nobility. It’s the opposite in both mood and religious inclination to ‘The Jesus Syndrome’, which precedes it, both here and in the long out of print Satan collection. It’s a deliberate reiteration of the lengths the Judges will go to in order to prop up their system.

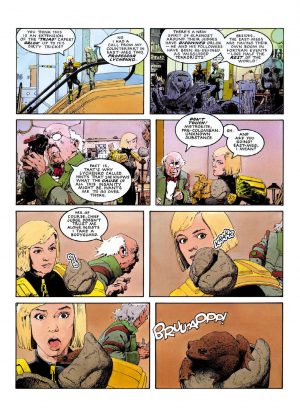

The final two stories are also thematically connected, the first being reflected in the second. ‘The Protest’ introduces the idea of a city mind infecting the citizens on the basis that the Judges have tipped the system too far in their favour. Grant supplies a suitably cynical and funny response. ‘R*volution’ is very different, but also considers suppression of the individual. “My composite mind has made me happy, rich and well balanced”, explains the villain of the piece, “I understand the patterns of the universe and can exploit them at will”.

For all the ideas and intellect Grant puts into the writing, which shouldn’t be under-rated, it’s Ranson’s epic vision that leaves the greatest impression. Most pages are almost photographically composed with inordinate care by Ranson applying delicate colours between his fine lines, and showcasing a vast breadth of influences. His Satan is suitably Old Testament, but into that story he funnels a montage of human atrocity, Gustave Dore-style shading, the vastness of space and some spectacular archaeology, that something of a calling card. His work on the title story is even more spectacular. Grant intends glimpses into the unknown and Ranson’s thoughtful art supplies that in a way that other artists couldn’t. It’s the comics equivalent of John Lennon asking George Martin to supply the end of the world for A Day in the Life, and like Martin, Ranson pulls it off. He applies the same dedication to the shorter stories, always visually imaginative and elegant.

With no disrespect meant to some of the other artists who’ve drawn Anderson, Ranson is the master, and if you want Grant and Ranson’s efforts at their peak, this is the collection to find.