Review by Ian Keogh

Two thousand years after he betrayed Jesus, the biblical Judas still wanders the Earth, condemned to immortality for his transgressions. Well, a form of immortality. When Jesus returns to Earth, Judas will have served his time, and for him that can’t come soon enough. However, he’s not the only remnant from two thousand years ago, and the first of the others we meet is Matthew, he of the gospel fame, living a very different life from what may be imagined, one of decadence and indulgence.

For some people W. Maxwell Prince will be treading very shaky ground by updating us on not only how Judas has been keeping over the centuries, but looking in on others from the twelve apostles/disciples from Jesus’ time. They’re also immortal, and all are lost to one degree or another. However, when Judas begins to enquire about how he might commit suicide, ripples are generated. To begin with there’s a sense of deliberate provocation about what plays out, a poking of the hornet’s nest with a sharp stick, but that idea gradually fades as Prince is investigating personal stories and how much about our lives is beyond our control. A lot of interesting ideas are thrown out as Judas become reacquainted with people he’s forever tied to, no matter how different they are now, but there’s not enough structure to those ideas. No sooner is something introduced then it’s sidelined in favour of something else, although in some cases there is a return, and some throwaways, such as mice developing religion, are very funny.

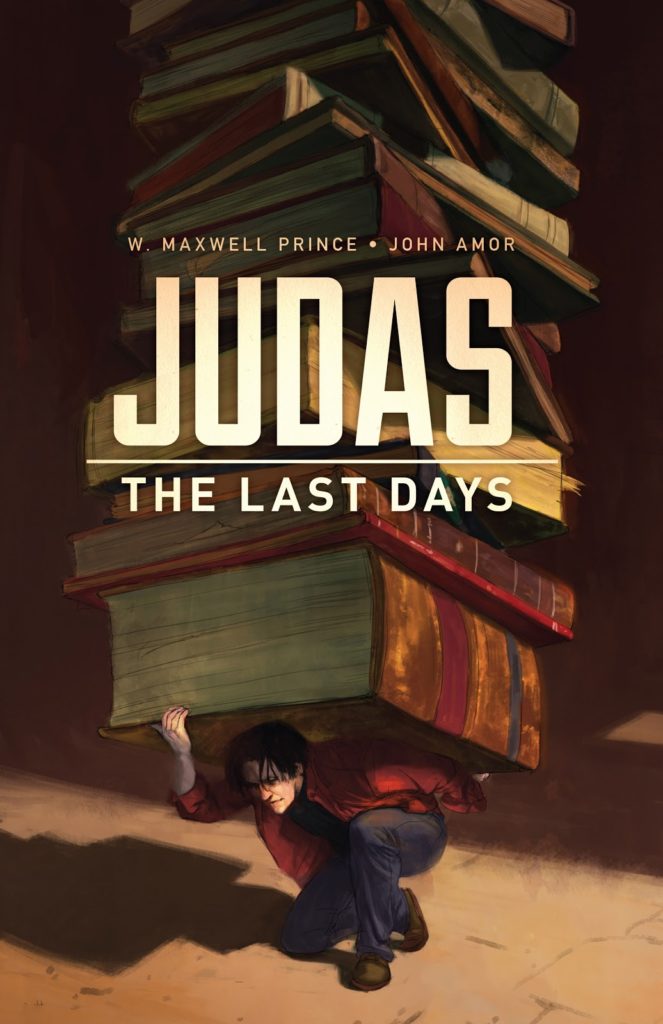

A similar frustration concerns the art. John Amor isn’t quite the professional yet. He’ll produce a great Bosch style spread of devastation, and there’s an accomplished portrait gallery near the end, but too many of the basics are lacking. The viewpoints from which people are seen could be more imaginative, and the figures themselves are stiff, although convey the necessary character. Perhaps if there were greater subtlety to the colouring Amor would look better, but there isn’t. However, a central point is that all stories can be changed, so maybe new colouring if there’s ever a reprint.

When Prince hits the spot, he’s great. Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus is dazzlingly conceived, if perhaps supplied in a way that’ll offend many Christians, and it also strikes to the heart of stories being the only truth. It’s a very 21st century, digital age message. Unfortunately, Paul is the catalyst for much that happens from halfway, and although it’s disguised a little via polemic, he might as well be Doctor Doom. Take what you will from the ending as well, be it profundity or hippy dipshit. There’s a lot to admire in Judas, the Last Days, but also much to frustrate.