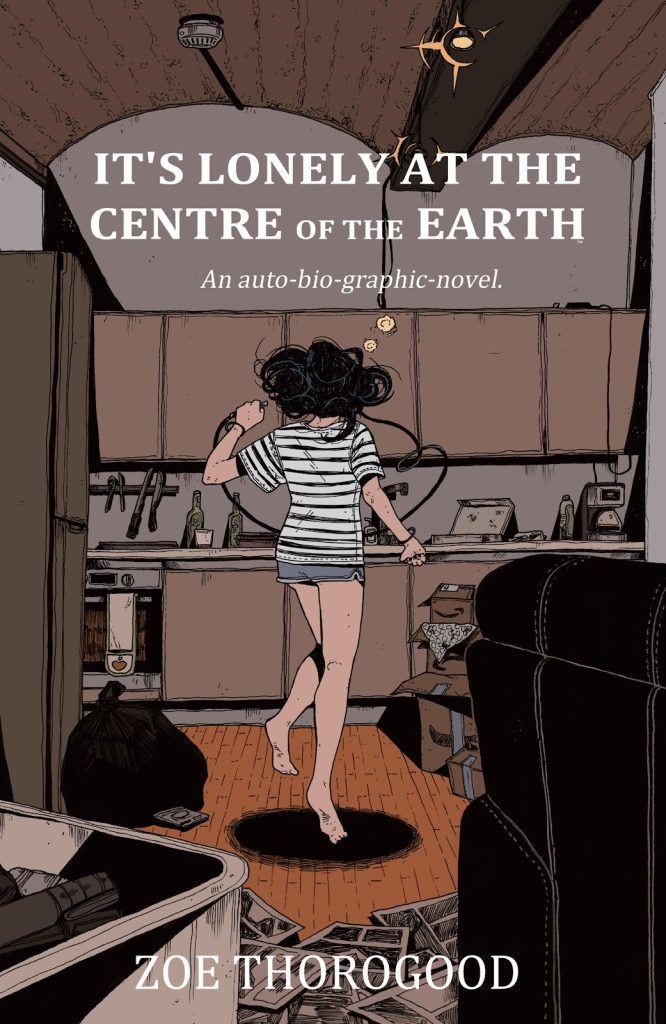

Review by Frank Plowright

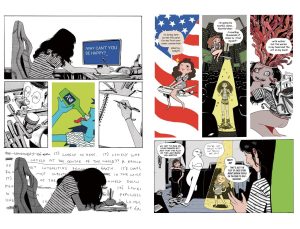

It can seem It’s Lonely At the Centre of the Earth is all over the place, with mixed art styles, mixed methods of storytelling, breaking the fourth wall and startling differences in colour. The artistic variation reflects mood, the assorted avatars represent different facets of Zoe Thorogood’s personality, and the entire approach concerns her also being all over the place as she copes with the depression that’s afflicted her for ten years since her teens. As such it couldn’t differ more from the positive spin on tragedy Thorogood applied to The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott.

She decides to keep a journal for six months, and this is the result. However, to call this a journal falls way short of the mark. It’s more a stream of consciousness ramble across the months, stopping off to make a point, looking back at what might have gone better and analysing her feelings.

Art as therapy? Definitely. However, other graphic novels take depression as a topic, yet none have the sheer artistic verve Thorogood applies. While intended to represent the confusion felt, there’s nevertheless something orderly about the art even as it switches from visceral scratchiness to a precise portrait with psychedelic colour background. There is self-awareness about a facet of depression being self-absorption, seeing everything in the world in terms of oneself, and Thorogood satirises this while still pouring out her heart. It’s brutally honest, not sparing herself or readers, and that’s a good thing as too many of us still think the solution to depression is to pull yourself together and struggle through. It certainly seems the attitude of the head teacher shamed. Her response to a 14 year old girl concerned about four classmates who’d attempted suicide is to note it’s statistically likely before threatening to call the girl’s parents if she doesn’t return to class.

Some themes recur, distressingly suicide, with the reproduction of a suicide note written when fifteen, and the thought of starting again, which is incorporated into what becomes an extremely complex narrative. Like Churchill’s black dog, Thorogood personifies her depression, here as a grotesquely smiling floating head in a cloak, but it’s just one of so many interesting visual moments. Earlier selves are the baggage taken to the airport, clever juxtapositions occur and the talent shines from every page. And while the focus rarely drifts from the narrator, there are some compelling anecdotes as well.

Taking a meander through someone else’s mind isn’t always what you want it to be. In a different world being young and talented would reinforce the idea of life being worth living, but it isn’t the case for Zoe Thorogood, so heartbreakingly sad. It’s to be hoped that one day she’ll realise how intense honesty and natural inclination has resulted in a visually stimulating graphic novel the likes of which has rarely been seen.