Review by Ian Keogh

History chooses its moments and what it chooses is often very random. Take Hook Jaw, a spirited adventure strip thrust into infamy in 1976 when adverse publicity about the excessively violent content of its anthology home, Action, saw an almost instant cancellation, with the final issue pulped after printing rather than distributed. Action had been devised by Pat Mills as an adventure comic for boys that represented what life was like for many in the depressed 1970s, reflecting their world and offering a sense of empowerment via strips where only teenagers survived an apocalypse, and another about football hooligans. Few kids of the era had come across a great white shark, but most had seen Jaws, and Hook Jaw was a response to the era’s most successful thriller film.

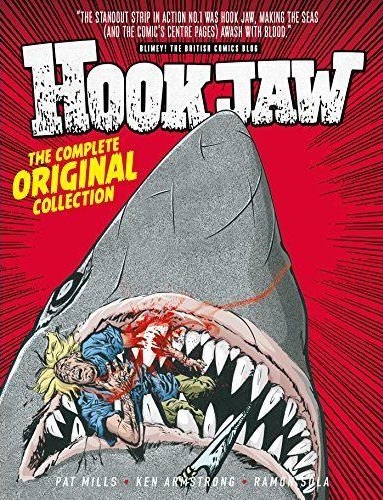

Hook Jaw sported a magnificent design, part of his tail fin shot away, and as if his own fearsome set of teeth weren’t enough, he paraded the seas with an extra weapon, the end of a harpoon protruding from his jaw and providing his name. How he acquired this distinctive look is explained in the opening story, filtering in aspects of Captain Hook and Captain Ahab.

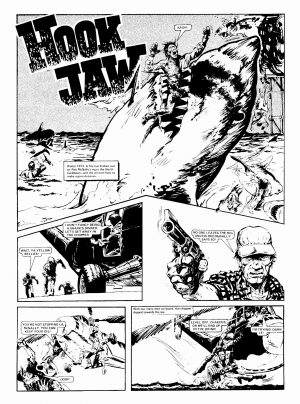

Mills plotted the episodes with some input from scripter Ken Armstrong, and in his introduction writes of an expectation that the shark would kill someone every episode, and as ingeniously as possible, a promise he gleefully fulfills. His further claim that the often gratuitous violence was recognised by readers as nature fighting back against the despoilers of the world is dubious, although he and Armstrong certainly painted the villains black and motivated by greed, with the human cost irrelevant. Oilman Red McNally over Hook Jaw’s opening serial typifies them. When the series hero Rick Mason asks why he wasn’t warned about sharks, McNally’s typically callous response is “I didn’t think it was necessary. Anyway, ya got out alive, so what’re ya bellyachin’ about?”

What Mills rightly refers to as the raw energy, was seen by others as excess, with Ramon Sola’s sample art providing a representative look at the violence. There wasn’t any softening of the likely consequences of meeting a great white shark, and the buyers of the 1970s received a full dose of gore for their seven pence, with no shortage of improbable action. After a few episodes of McNally and his escapades, the ante is upped by a passenger plane crashing near his rig. It’s in hilariously bad taste, and the gore is inventively sustained. Mason survives to have further battles, and Doctor Gelder and Jack Gunn, subsequent foes for Hookjaw, are based on McNally, prioritising their profits above all else. While Hook Jaw’s episodes follow a formula, in small doses it’s still a thrilling and often funny formula.

An irony is that by the time the axe fell, visually at least, Hook Jaw had already been toned down. Felix Carrion’s art still shows Hook Jaw chewing people up, but nowhere near as explicitly as Sola’s pages with body parts in the background and blood dripping from Hook Jaw’s mouth. He’s a far more traditional storyteller in other respects also, so even sending Hook Jaw to Southern England fails to thrill as much. The collection presents the half dozen episodes never previously seen after Action’s instantaneous cancellation, but they’re tame and generic compared with the earlier thrills. Not featured is the reworked strip from a toned down and teeth drawn relaunched version of Action.

In case its of interest, Mills and collaborator Kevin O’Neill satirise the furore over Action in their novel Serial Killer.