Review by Graham Johnstone

Harvey Kurtzman is one of the most important creators in comics. He was a writer, artist, and editor, creating the original Mad, and various action titles for EC in the 1950s, and his 1959 Jungle Book was one of the first graphic novels of original material from a mainstream book publisher.

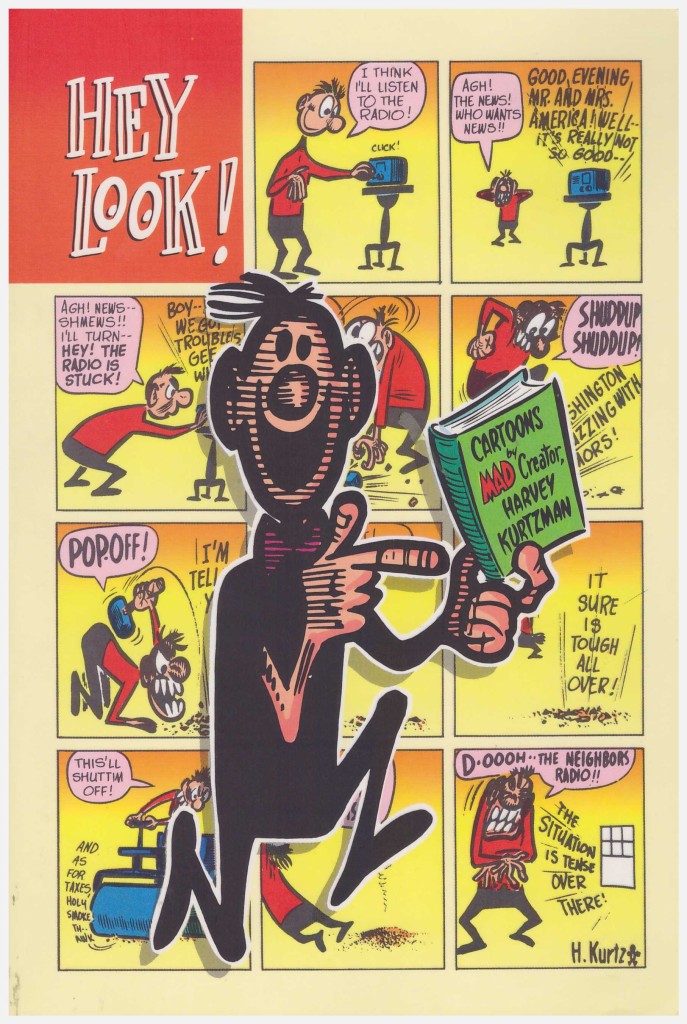

He honed his craft in the 1940s with Hey Look!, a series of inventively humorous single pages. These were published in a range of titles as inventory or fillers, and are collected here for the first time.

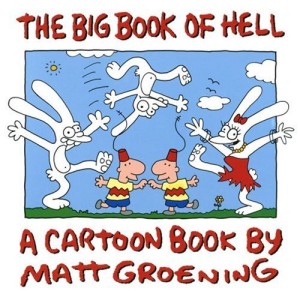

The premise is minimal: there’s smart little guy and a not-so-smart big guy, and they engage deeply and innocently in whatever Kurtzman thinks up. The madcap humour is perhaps influenced by the Looney Tunes animations of Tex Avery and Chuck Jones, however, Kurtzman translates it to comics. He creates the movements, leading our eyes dizzyingly about the page. The action breaks out of the panels. He’s also a master of expressive faces and figures, rendering them with confident, fluid brush strokes that indicate shadow and form through varying thicknesses. He only makes it look simple.

He’s also able to illustrate the necessary props correctly: the page ending “Run for your life the meat thawed out!” wouldn’t be nearly as funny if he couldn’t draw realistic rampaging bulls, sheep, geese and hairy mammoths!

Hey Look! was a real laboratory for Kurtzman. The style is continually changing, and not even in a simple A to B trajectory. On page 116 the ‘backgrounds’ are simple black, white or loose vertical lines. Then on the very next page there are intricately inked realist landscapes. Turn the page and the backgrounds are just white, and so on.

Kurtzman uses what we might call ‘sequential exaggeration’ – each panel pushes the idea a bit further. We see the same technique on the facing page – Big buys a puppy, but it keeps chewing things to destruction: a bone, a slipper, a chair, a metal lamp, and finally, Big himself.

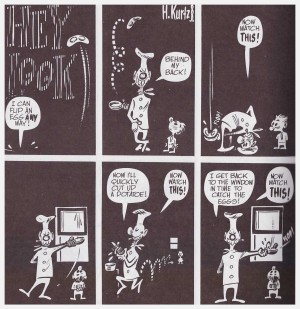

About a third of the way through Kurtzman makes a step change, and really goes to town with the invention and humorous references to the comics form. On one page Big is trying to open a over-boiled egg- he throws it at the floor and it ricochets dangerously off the sides of the panel. It’s eggs again on page 146: Big is showing off his flipping prowess. Behind the back he flips the omelette in the air and goes to chop some potatoes before coming back to catch it. He does a somersault and the egg stays still. The punchline here is he’s flipped the panel over – it’s a drawing of a blank piece of a paper with a corner folded over to show ‘the end’.

Kitchen Sink Press and editor John Benson are to be applauded for compiling this complete and chronological collection. Yet they were never intended to be read together, and, like babysitting boisterous children, the fun can exhausting. Benson’s introduction reports that EC boss Bill Gaines, spent an whole hour laughing out loud at them. That may not be guaranteed, but anyone with an interest in funny, inventive comics should enjoy these. Connoisseurs of the form can admire Kurtzman’s skill, restless development, formal games, and bold inking.

The last thirty-odd pages mop up various other Kurtzman shorts of the period, and highlight his range. Genius is a smart and ruthless kid – a proto psychopath. Egghead McDoodle is a more gentle humour, like Bushmiller’s Nancy. Potshot Pete though, most closely predicts his late, fluid, expressive art style, and the longer stories point directly to the style he would soon use in Mad.