Review by Ian Keogh

Liliko is a fashion and advertising model with an exceptionally high recognition factor, an influencer in the days before such a trade existed. She’s on the cusp of taking a step into movies and recording an album when we meet her. It’s not a flattering introduction on the part of Kyoko Okazaki, who presents naked narcissistic ambition combined with a talent for concealing that when cameras are present, when Liliko transmits as natural. Okazaki reveals early that very little about Liliko is physically natural. The numerous surgical procedures she’s undertaken are now beginning to have an effect, and her massive drug intake is resulting in a schizoid personality.

Because the subject matter lends itself to shooting fish in a barrel, a lazy creator would do no more, but Okazaki’s concerned with realising a broader picture, achieved in the opening chapter by contrasting the reality with the Liliko’s public personality. While Liliko is to her fans at the peak of her popularity, she’s aware that peak is going to be short-lived. And then what? Also rounding out Liliko are the supporting cast. Her put-upon and conflicted assistant Hada has little life other than seeing to Liliko’s whims, abuse a heavy part of the job, and her appalling, manipulative manager, whom she refers to as “mother” hints at what’s made Liliko.

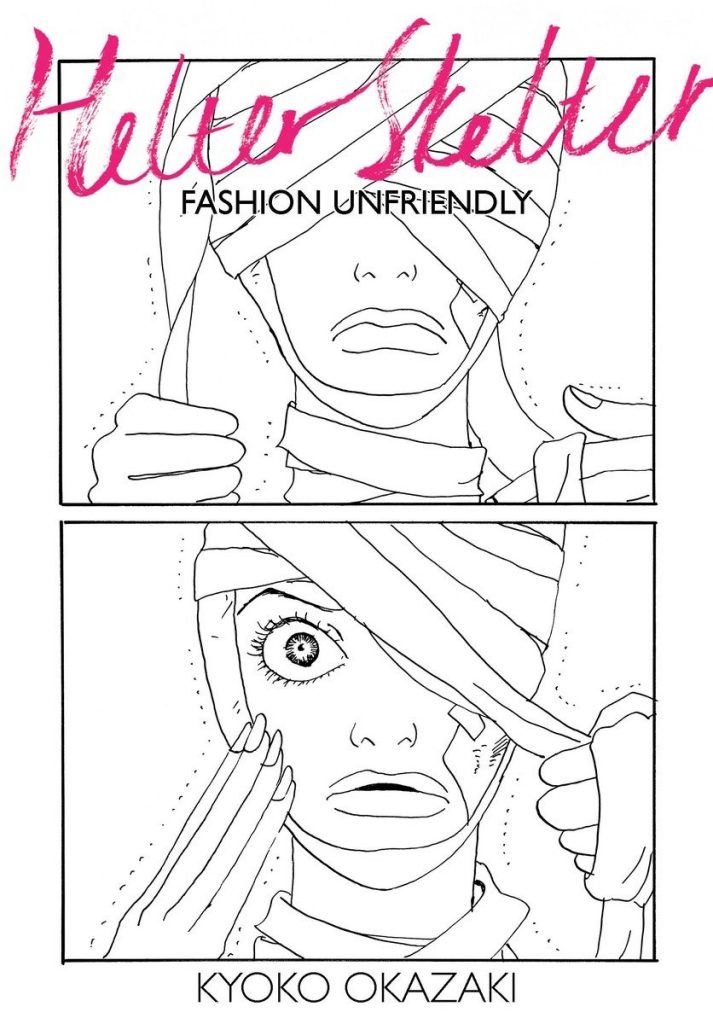

The bulk of Okazaki’s art looks simple as she relies on lines almost exclusively, with smudges of grey indicating the occasional shadow. We become so used to that depiction of the cast that when she changes tack to show a photo perfect scene of Tokyo at night it’s a surprise, but it also underlines the main theme of presentation not being the same as truth.

In case there’s that expectation, Helter Skelter has nothing to do with either the Beatles or Charles Manson, but even before it’s referenced Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond comes to mind. When the film is mentioned, there’s no doubt about the path Okazaki intends to follow, and we’ve already had narrative captions referring to events as the past. Liliko has an awareness, but not enough to see beyond what she so desperately clings to, considering its validation as perpetual entitlement, resulting in the monster she is.

There’s an admirably twisted quality to Okazaki’s writing and to her lack of sentimentality, and it’s what makes this measured disintegration more than a car crash. Okazaki details how almost everyone sees Liliko just in terms of what she can provide them, not in any way as a person, meaning almost every relationship she has is as artificial as she is. However, while that might be enough to induce some sympathy, Liliko eventually crosses a line between being a diva and criminal activity, dragging down others with her, and this provides an adjunct to already ongoing police investigation. That’s one of the weaker elements, the investigator too whimsical and given to enigmatic and fanciful statements.

While the set-up is compelling, Helter Skelter’s overstays its welcome, padding the plot and supplying an ending leaving something to be desired. Retribution would be too simple, and Okazaki avoids it, but the enigmatic policeman’s involvement is already unconvincing, and the indications are that Okazaki intended a wild swerve when picking up the story again. It’s probably just as well it wasn’t continued, as what Liliko represents is a powerful statement, and moving her into another mode for the sake of continuation would be artistically redundant. What we have sustains the interest and makes its points effectively over the first half, ensuring pages turn until the end.