Review by Frank Plowright

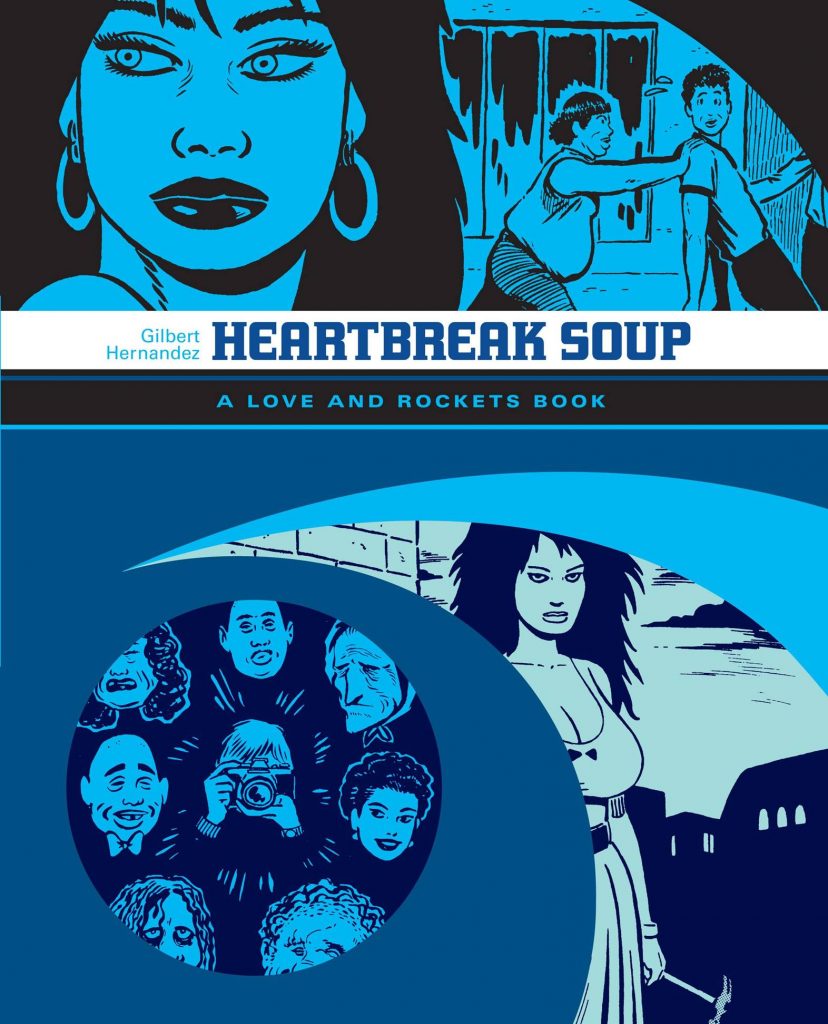

The 2007 reprints of Gilbert Hernandez’s Palomar stories split them over two bulky paperback editions, of which this is the first. The contents page doesn’t supply the story dates, which is a pity as it means his phenomenal development as both a writer and an artist isn’t as evident as it should be. Everything over nearly three hundred pages was produced during an incredibly fertile period over just over three years, during which Hernandez was producing other material besides.

‘Heatbreak Soup’ establishes the town of Palomar and its inhabitants, introducing them via their reactions to the arrival of the glamorous Luba and her four young daughters. Subsequent stories are set at least ten years later, although frequently involve flashbacks, and their increasing quality now overshadows how different and ambitious this was in 1983. The art now seems crowded by excess text, and some storytelling could be more efficient, but it’s still very readable, throwing in little details to be explored in later visits. The triumph remains the convincing construction of a wide and multi-faceted cast, many eccentric, who rub along despite their differences, as people have to in small towns. The ethnic tourism of Palomar being remote and in Central America adds exotic locations and customs, to which Hernandez fuses strangeness not found in any real place, and some mystical realism from his biggest influence at that stage, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The art is tidy and emotionally strong.

Skip to the penultimate story ‘Duck Feet’, though, and the difference is immense. The storytelling is far more sophisticated, the mood switches effortlessly between tragedy, the comedy of Luba stuck in a hole, and surreal, hallucinogenic times with the art effectively reflecting the changing moods. It’s slathered in black ink for the darkness and amazingly expressive for the light. Hernandez is always strong when giving children personalities, yet keeping them within their age range, and that’s exemplified by the helpless Guadaloupe here.

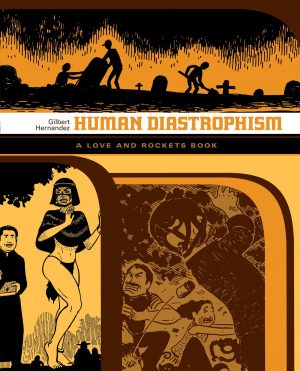

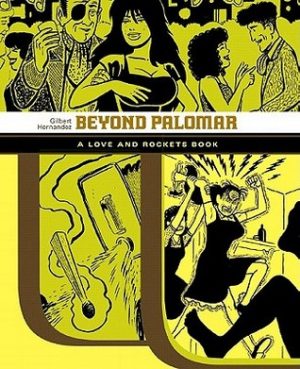

Between those two stories Hernandez spotlights Palomar’s assorted inhabitants, although it’s a rare story not seen from either Luba or Heraclio’s viewpoint. He’s the most grounded resident, and a highspot among an embarrassment of riches is a piece in which he explains his devotion to his wife Carmen. We also meet the fatally alluring Tonantzín, hard-nosed Sheriff Chelo, the asthmatic Vicente, the tormented Jesús, the tragic Toco, Martín marching to his own drum, infatuated Angel, the speedy Diana and many others, each meticulously constructed. So are the stories, all with an emotional dramatic richness and understanding of humanity rarely present in someone still in their mid-twenties. Astonishingly, Hernandez still hadn’t reached his peak, found as he brings his 1980s spell in Palomar to an end with the subsequent stories, collected as Human Diastrophism in the 2007 paperbacks.

The 1980s UK editions of Heartbreak Soup and Duck Feet feature roughly three-quarters of this content, and the 1987 Heartbreak Soup and Other Stories some of it. It’s all found in the hardcover Palomar, and spread across the earlier Love and Rockets paperbacks Chelo’s Burden and Duck Feet.