Review by Frank Plowright

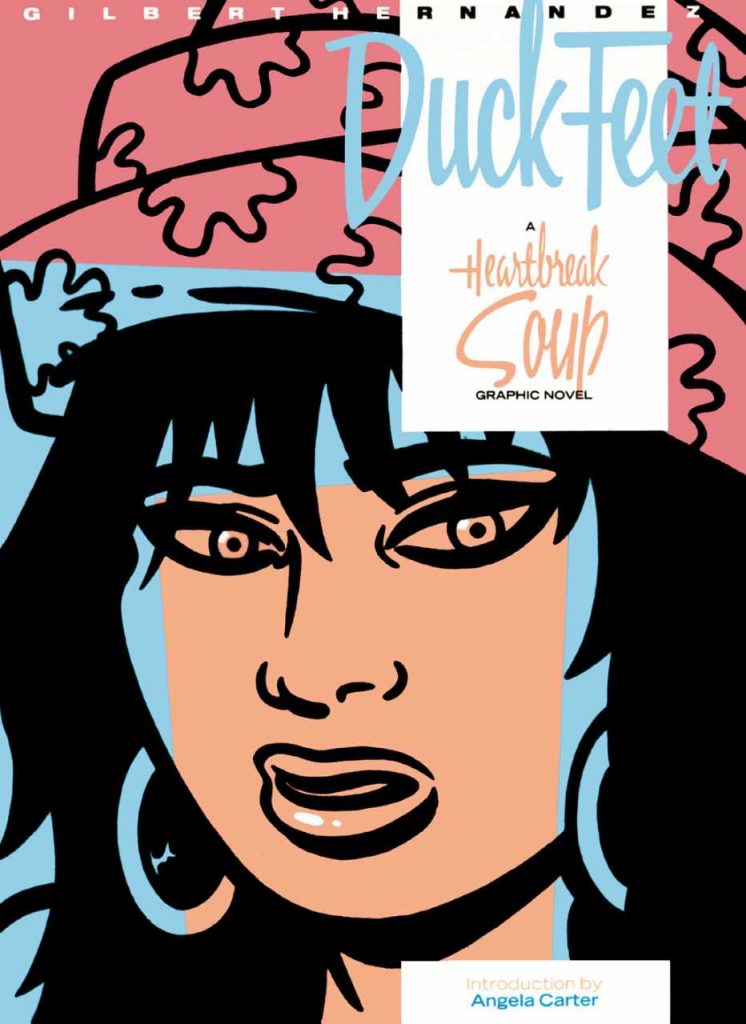

Gilbert Hernandez’s looks into the lives of Palomar’s residents were labelled as ‘Heartbreak Soup’ stories by Titan Books back in the day, the name taken from the title of the first visit to Palomar as seen in their first collection. This selection has a greater variety, only the title story and ‘An American in Palomar’ extending to two chapters.

It’s where Hernandez starts to add surreal items to Palomar, one short story entirely devoted to the collection of large edible slugs called Babosas by Tonantzín, who then cooks them and sells them as a delicacy. There’s a greater influence on the American visitor, photographer Howard Miller who’s shown the strange temple in the hillside lake. As good as Hernandez has already been, the use of Miller as the mirror reflecting Palomar’s residents via his own intrusive cynicism is a new highpoint. He exploits naivety, and lacks understanding, only seeing people as adjuncts to his projected artistic vision, and pays the price for that.

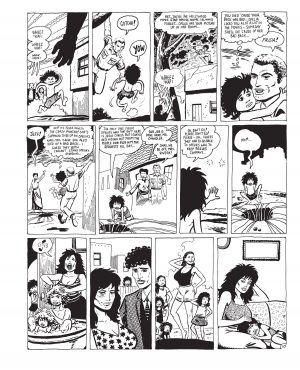

In his mid-twenties when he created these stories, Hernandez displays a mature understanding of human emotion, and delivers it in dramatic spades, particularly passions associated with love. Envy, jealously, abiding love, obsession, and regret all feature. A balance that time’s not yet distorted is how Hernandez has men behave as men, with all the coarse comments and offensive gestures that entails, but always definitively put in their place by the women. It’s effectively seen throughout, but emphasised in ‘Boys Will Be Boys’.

Palomar is a small town, and the lives of the residents are entwined. Some secrets everyone knows even before Hernandez reveals them to readers, while others are between two people. Whether Hernandez constructed the relationships as he went along, or before he began working on his Palomar material, he refers often to the past. It’s a more sophisticated version of continuity obsessed superhero stories, using crucial incidents to inform ordinary lives, showing our past never dies until we do. It features heavily in Les Misérables and One Hundred Years of Solitude, both novels namechecked, and also supplying the narrative richness Hernandez applies.

‘Duck Feet’ closes the collection, running a glorious plot only Hernandez would come up with. Palomar is visited by an old woman considered by many to be a witch, a bruja, something that could be proved if people could see her duck feet. Meanwhile Luba has fallen down a hole and is too embarrassed to ask for help, so has her young daughter Guadalupe running around town for food and supplies. It starts as ridiculous, yet takes a sinister turn when many people in town fall ill. Increasingly hallucinogenic, Hernandez draws on his non-Palomar characters, Jeff Chandler and Frida Kahlo, and his inner Ditko. It’s also the start of Tonantsín’s individual form of political awareness that will play such a part in the next instalment, Human Diastrophism.

The stories in Duck Feet still delight. All human life is supplied with a warmth, understanding and complete lack of judgement, and to consider after reading that Hernandez would become better still, is almost beyond belief.

An American collection titled Duck Feet also exists, containing some of these stories, but featuring the work of both Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez. These stories all feature in bulky hardcover Palomar collection, and in the 2007 Fantagraphics collection Heartbreak Soup.