Review by Frank Plowright

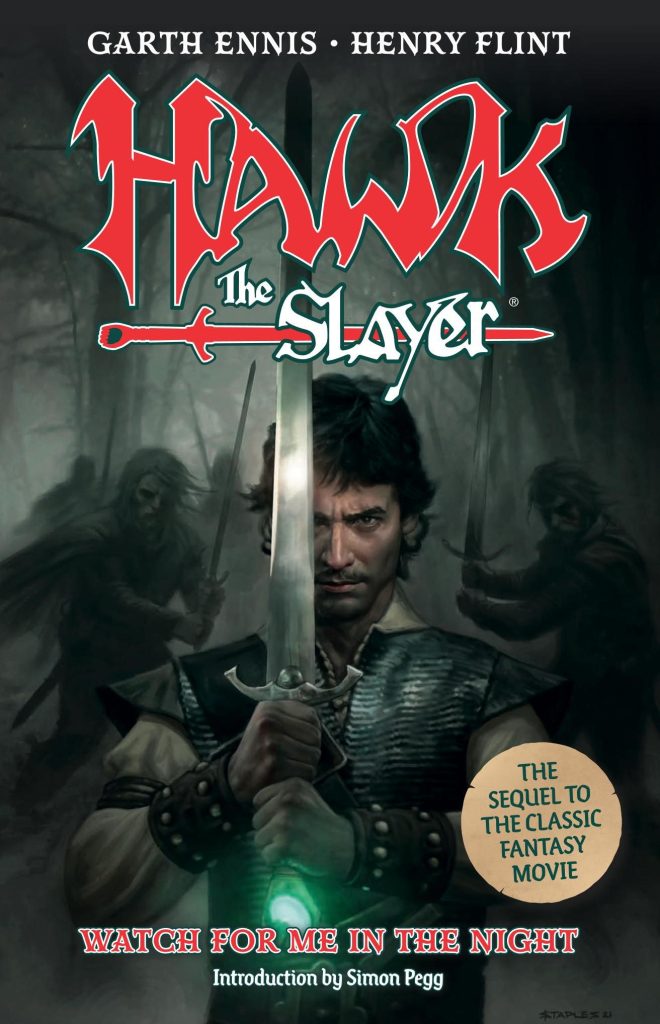

As Simon Pegg notes in his introduction, Hawk the Slayer remains a divisive film. Even the enthusiasts who contribute to Rotten Tomatoes rankings can’t raise a 40% rating from the paid critics higher than 57% (as of writing). You had to be a certain age at a certain time to fall under its spell, an age where you didn’t realise the movie stitched together every blindingly obvious fantasy cliché with a few that were more original, but equally lifted. Pegg was that age, and so was Rebellion Games and 2000AD publisher Jason Kingsley, who all these years later can live the dream by hiring Garth Ennis and Henry Flint to provide what cinema never did: a sequel.

In the movie Hawk and his brother Voltan are arch-enemies who clash, primarily over a magical sword. After Hawk finally kills his treacherous brother viewers see the body carried off by a wizard. Can it be Hawk’s not had his revenge after all?

Fantasy isn’t known for having any great appeal to Ennis, and the satirical film precis related by a bar owner indicates that’s not changed. Those old enough to remember the film when released might like to imagine it as narrated in the voice of Frankie Howerd. Flint channels Carlos Ezquerra to illustrate this section.

Ennis looks in on Hawk and the mates who survived the film’s ending, adding a minstrel occupying the borderline between fan and stalker seemingly based on Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson as he was in the 1970s. It’s several years later, but Hawk remains concerned about Voltan’s possible return from the dead. Turns out, he’s right to be worried.

In terms of originality Ennis offers little more than the movie except to overlay the earnest fantasy stereotypes with a sardonic veneer, particularly revelling in the feebleness of Wain the minstrel. He picks up a few loopholes left by the movie, but Flint’s fully detailed contribution requires more effort. He seems influenced by classic illustrators of children’s books, especially Arthur Rackham, and presents a fully constructed world of heroic poses, gnarled vegetation and plentiful rocks. It’s art to look closely at.

Those of a certain generation and age ought to feel that Ennis and Flint have done them proud in providing the sequel that took forty years, but anyone not enraptured in 1982 will have to make do with some great art and a few laughs.