Review by Ian Keogh

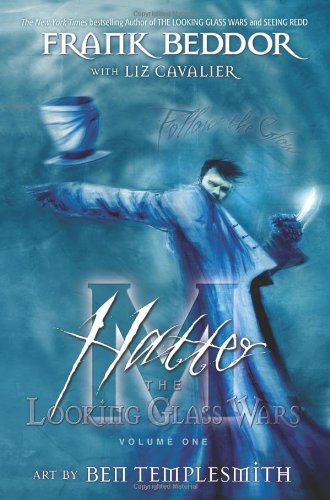

In his Looking Glass Wars trilogy of novels, Frank Beddor repurposed Lewis Carroll’s surreal Wonderland characters into altogether more sinister and deadly beings. Take Hatter Madigan, for instance, better known as the Mad Hatter, but in Beddor’s world the millinery trade is almost a discipline, involving protective duties and use of hats as weapons.

If this all seems very Batman foe, it isn’t. Oddjob from James Bond would be a nearer comparison, as Hatter works his way around late 19th century Europe attempting to locate Alyss, a Wonderland princess lost somewhere on Earth. As Beddor would have it, what Carroll provided as entertainment exaggerated and trivialised some very dangerous people.

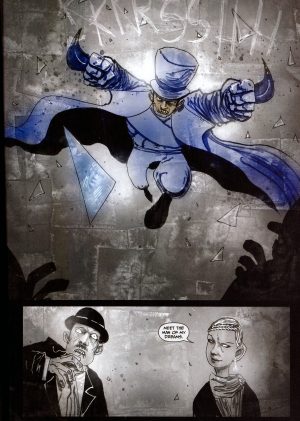

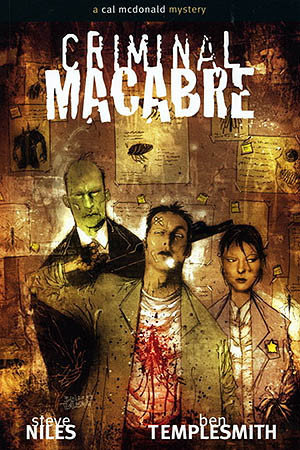

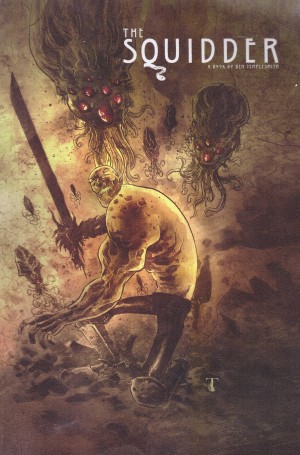

If Ben Templesmith is selected to illustrate a story it indicates that a distinct look and mood is required, as his scratchy, blurred figures and predominantly brown colouring are utterly recognisable. You don’t hire Templesmith if you want your story looking generic. Beddor and his writing collaborator Liz Cavalier channel the dingy, grimy side of Victorian literature, and there are some imaginative effects that Templesmith brings to life. People from Wonderland are surrounded by a bright aura only other inhabitants can see (although the very creative on Earth share the effect) and Templesmith uses this effectively in a dark world. He’s at his best in the final chapter where his designs for some fearsome machinery are memorable.

Hatter M isn’t an adaptation, but instead runs parallel to the novels, adding depth and detail to a popular character, but the original Hatter was defined for a specific purpose in a specific surreal mileu. Removing him from that and turning him into a Victorian superhero in effect is far sillier than the original intention. As characterised here, Hatter is a 19th century Wolverine, single minded and using blades for all kinds of purposes as he carves his way across Paris and Budapest in search of his lost princess. It’s determined that his distinctive top hat is some form of protective device, a functional computer of sorts, that enables much of his talent, and provides easy narrative exits from tricky situations.

To claim that the cast of classic out of copyright novels should be sacrosanct is nonsense, but on the evidence of Hatter their transformations are so drastic that only their names connect them to the original material. There’s no need for Hatter to be who he is, so would Beddor have been better working his story around his own concepts. Perhaps the novels provide a greater connection, and that three were published indicates plenty of people thought Beddor’s transformations a viable reworking. Also indicating a greater popularity is that Hatter M proved more than just a detour from the novels, and it eventually took five graphic novels to complete his task, Mad With Wonder following.