Review by Ian Keogh

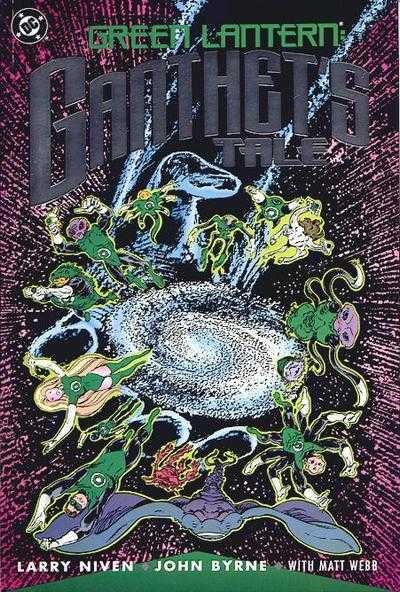

Back in 1992, commissioning acclaimed science fiction author Larry Niven to write a Green Lantern story was quite the coup, but what the publicity didn’t spell out was that Niven contributed the plot only. The breakdowns and scripting were handled by John Byrne. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Long established in Green Lantern mythology was that the small, pale-blue skinned Guardians of the Universe maintained an enormous corps of Green Lanterns over every space sector. One of these Guardians, the Ganthet of the title, turns up at Hal Jordan’s door explaining that an entire race requires saving. Other previously established lore has the Guardians being part of the Malthusian people that evolved millions of years ago in Earth time, super-advanced and immortal. Able to adjust reality with their merest thought, they ran into problems with children’s immaturity. Their solution was to stop breeding, desert their home planet, and colonise others in small batches. Evolutionary adaptation has resulted in vastly different forms of Malthusians throughout the universe.

Another known aspect of the Malthusians was that one grew curious and desired to view the origin of the universe. Krona witnessed a giant hand freeing a celestial nebula before his machinery detonated. This tale has always been assumed to be literal, but Ganthet believes otherwise, and considers Krona’s machine has taken its own devastating toll on time.

It’s difficult to know how much of the plot has been filled in by Byrne, but Ganthet’s Tale rambles a fair bit before shifting into the main premise, and that wasn’t a characteristic of Byrne’s work at the time. The finger for the meandering therefore points in Niven’s direction, and it reduces the essence of what’s eventually revealed as a clever idea reconfiguring much of the Green Lantern backstory. The other element of the writing is that it’s very much of its era, with bulging word balloons and some dialogue that no-one would actually say out loud.

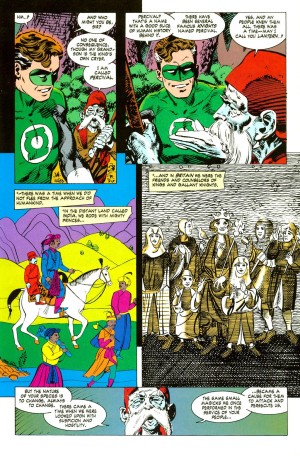

If there are concerns about the writing, there’s no problem with the art. Byrne was always an exceptional and dynamic storyteller, and here he’s able to throw in a few experimental touches. There’s a fine black and white abstract spread toward the end, and before then he illustrates a few panels in a style representing their time and location (see sample image).

Time and constant revisions of DC continuity have reduced Ganthet’s Tale to a curiosity. That it was among the earliest standard comic size graphic novels produced by DC is now of no relevance. It may be that Niven’s fans are tempted, but clever though the plot fulcrum is, Niven’s prose work is far more imaginative.