Review by Ian Keogh

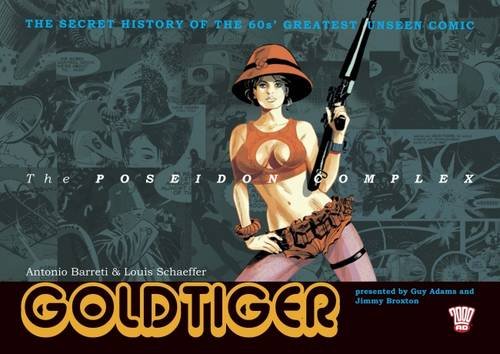

Goldtiger is a very clever and stylish pastiche, meshing elements of the traditional action/adventure newspaper strip with faked background research presented with a poker face. It’s supplied as a rediscovered 1960s obscurity purportedly written by hack writer Louis Schaeffer producing his first newspaper strip, only to then see his work distorted by Italian artist Antonio Barreti. He drew much of the content from a sanatorium after a nervous breakdown, and his additional contributions ensured that the strip was unsuitable for the conservative public of the era. Modesty Blaise pushed at boundaries of taste, but Goldtiger breached them

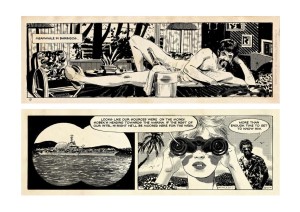

The strips are presented as if cut from newspapers, compiled, and pored over many times, the production supplying smudges, spillages and browned paper, while other strips are almost pristine. Colour is a random occurrence. Jimmy Broxton, also an alias, creates a fabulous world of 1960s glamour populated by the strip’s two leads, fashion designers Lily Gold and Jack Tiger. They like a taste of mystery, and of the exotic, and it’s served up three panels at a time.

To maintain their fiction writer Guy Adams and Broxton have added authenticity via amusing introduction pages relating how Broxton was handed copies of what’s printed in a rundown area of Valletta, and appreciations by 1960s trendsetters (Sandie Shaw’s hair stylist no less). They then intersperse the ‘reprints’ with interviews, background correspondence, and associated illustrations, also providing editorial notes referring to missing strips, and rough layout sketches for others ‘missing’ in their full form. There are also strips where the nutty Barreti, not pleased with the quality of what he’s receiving to illustrate dispenses with the submitted plot and instead draws himself complaining about matters. These prompt Shaeffer to sketch the following instalments instead.

There’s a great deal of further insanity, but the best way of experiencing it is to read Goldtiger, which closes with attempts to morph the concept into a strip suitable for the early days of 2000AD.

Kitsch drips from the strip reprints, and the text insertions are side-splitting. The ongoing creative tug of war between skint writer and damaged artist, and the problems of the latter are extremely well presented, each successive setback piling on the hilarity. The content breaks down to approximately fifty percent comic strips, with the assorted accompanying material making up the remainder. This faux historical research is essential to the package, though, and the strips would be meaningless without this context.

Goldtiger is an admirable and successful attempt to forge something new from comics, and it’s a shame no publisher could initially see the potential. We can be thankful for those with greater faith and foresight who contributed to a Kickstarter campaign.