Review by Jamie McNeil

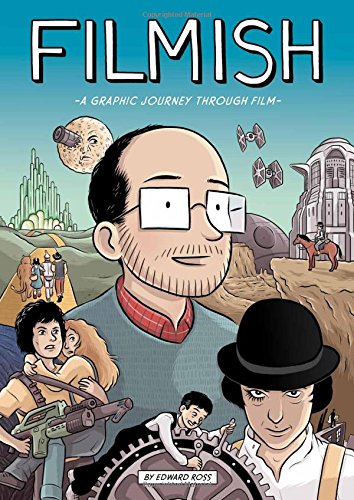

“A Graphic Journey Through Film”. That’s the tagline for Filmish, Edward Ross’ illustrated guide to the history and future of film, and what a journey it is! Written and illustrated by Ross, this is an approachable book on the subject of cinematic development that hides some hard-hitting observations within its cartoon style.

Produced entirely in black and white, a strength of Filmish lies in presenting, plainly in ink, scenes that struck a chord on release, but which may now seem dated due to the advancements in CGI and other effects. This means that scenes can be presented frame for frame as Ross draws them in sequence, strengthening his commentary a hundred fold. This sets it apart from other books on cinema, as copyright laws and such would limit them to one still from the film, but Ross’s right to artistic expression helps him circumvent that and really explain his point. For instance, Ross often interjects his own portrait (complete with reclining hairline) into various scenes as either observer or extra, highlighting the immersive qualities of film and its power to stimulate our imagination. This is as effective when he is presenting himself as a zombie to explain cinema’s relations with personal body image, or describing the rather stringent censorship of The Hays Code from the 1930s by placing himself as Moses from DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. There are no sacred cows here, Ross taking seven categories and parading both the positive and negative of the film industry. He points out how film has been used for education, indoctrination, suppression, oppression, liberation, and pure simple entertainment. As the book progresses so does the illustration and commentary improve, Ross’ confidence growing as he ingeniously uses quotes from directors, historians, and cultural theorists to explain his point.

Partly funded by Creative Scotland (known to be notoriously tight-fisted), Filmish avoids the cultural snobbery that tends to affect film fans. While books listing the films you must see before you die can inform your viewing, they also invoke inferiority if you haven’t seen them yet, or worse still, have and think they’re rubbish. Ross nurtures an interest in film, explaining the finer points of every genre from horror (often showing strong and liberated women as leads) to western (emphasis on strong, white, heterosexual men). His section on the purpose of film to strengthen or deconstruct notions of power and ideology is thoroughly fascinating, while his scenes from A Trip to the Moon make you want to go and watch it for yourself. What comes across is a genuine love for this medium of communication, gently encouraging you to look deeper at films whether you prefer blockbuster action, or the subtleties of world cinema.

Filmish makes you think deeply about the subject, to look at every angle rather than view it from just one perspective. This is rich material, so Filmish is not a read for one sitting. Take your time savouring each chapter, considering the different quotes and ideas posed. With its endnotes, filmography, and bibliography, it feels like a textbook but one you will genuinely enjoy reading. The worst thing that could happen would be for this gem to become a textbook, because its very purpose is to make film and its history accessible and understandable for the people meant to enjoy it – us! And Ross achieves that – Bravo!