Review by Karl Verhoven

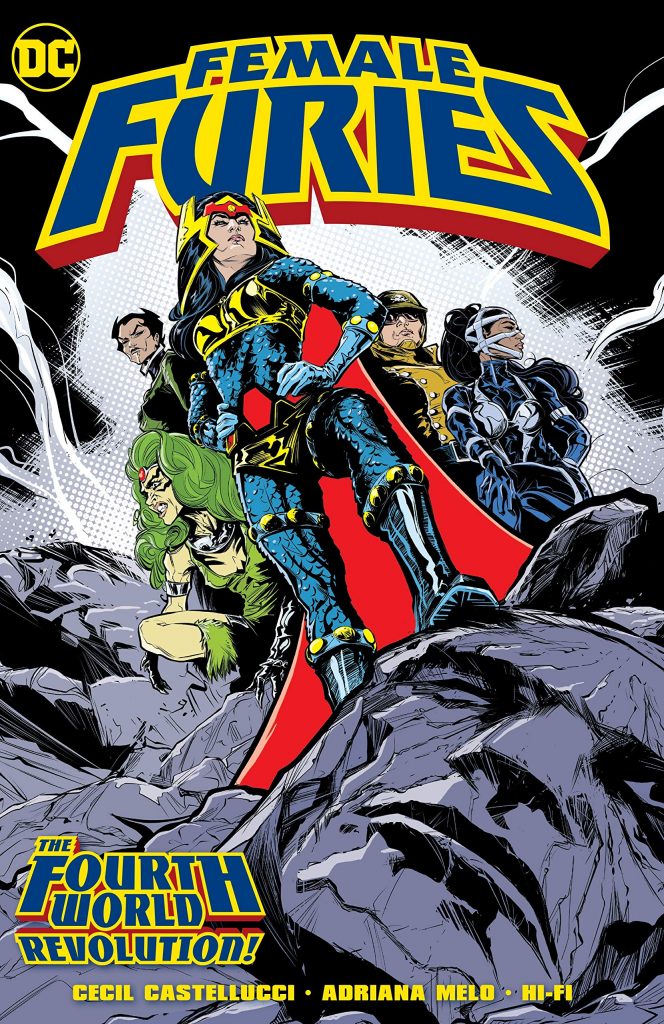

As announced in the opening lines, “The Furies are the most elite fighting force on Apokalips. We do things that most on our planet would cower from. We get the job done when others cannot.” It’s a fair calling card when it’s taken into consideration that Apokalips is the most appalling place in the universe, and over the years they’ve proved themselves formidable adversaries to all superheroes who’ve stood in Darkseid’s way. The Female Furies have survived them all, yet they have difficulty emerging with dignity from Cecil Castellucci’s attempt to recast them as anti-abuse campaigners.

In the most appalling place in the universe, Aurelie, then leader of the Female Furies, sees a ranking official with a young woman. It’s not the woman about to be tortured that offends Aurelie, but that the sleazy official suggests things will go easier if the girl submits to him. It resonates as Aurelie’s also being abused by a man with power. This is revealed after we’ve been subjected to a scene of the Female Furies auditioning for the Apokalips leadership in some grotesque talent show parody. There’s a message in there somewhere, if only the reader could figure out what it might be.

Castellucci continues onward in the same heavy-handed manner. Aurelie endures degradation and abuse, while we hear the unacceptable mitigating phrases used in the real world when oppressed women finally kick back: “typical of a female. They’re unpredictable”. Castellucci’s making a point no compassionate person can disagree with, but it’s undermined by the choice of venue. Apokalips is Hell. Do they have complaint procedures, compliance training and written warnings in Hell? Worse yet, the rock of Apokalips, evil incarnate, Darkseid behaves irrationally to slot into this world of abuse and exploitation, needing to have a cuddle from Granny Goodness every once in a while. She alternates between exploited victim and harsh taskmaster.

The second half of Female Furies concerns itself with the relationship between Big Barda and Scott Free, later to become Mister Miracle, how it compromises her effectiveness among the Female Furies, and what that leads to as we eventually reach the revolution of the title. Adriana Melo supplies solid, if slightly stiff superhero art, her strength being the selling of raw emotion, which is a frequent requirement.

It’s very difficult to work away from the idea of Castellucci attempting the right thing in the wrong place. Birds of Prey or any number of standard Earth-based superhero titles would provide a far more effective venue for a story highlighting abuse, but switching venues wouldn’t alter the lack of subtlety.

The collection closes with some of Jack Kirby’s 1970s work on Mister Miracle. It’s where themes and characters used in the main story originated, and also has points to make, about how adversity is never conquered by self-interest and about the power of dreams. Kirby’s often a more subtle writer than he’s given credit for, and makes his points without constant repetition amid an unpredictable story.

As a skim through the history of the Female Furies, The Fourth World Revolution is okay, but imposing the anti-abuse agenda makes no sense in context.