Review by Ian Keogh

From the 1970s the magnificently named Ervin Rustemagic ran a comic art agency from Sarajevo, a city in what was Yugoslavia when he began the business, and for many years afterward. His clients, both artists and publishers were global, among them American artist Joe Kubert, best known in the English speaking world for his DC work from the 1940s to the 1990s, but also the originator of several projects whose first publication wasn’t in English.

In the early 1990s separate nations fused together to form a country at the end of World War I exploded, committing atrocities in the name of freedom, but some motivated by a greater ethnic agenda than others. Although he maintained offices elsewhere in Europe, in March 1992 family concerns prompted Rustemagic to return home to newly independent Bosnia and Herzegovina, a state still in flux.

Almost immediately after Rustemagic’s return Sarajevo came under siege from Bosnian Serb forces, overtly following a policy of ethnic cleansing, their snipers shooting children in the street in order to take further shots at those who came to aid them. In the days before e-mail and texts Rustemagic’s contact with the outside world was via the faxes sent to friends. These form the basis of Kubert’s book.

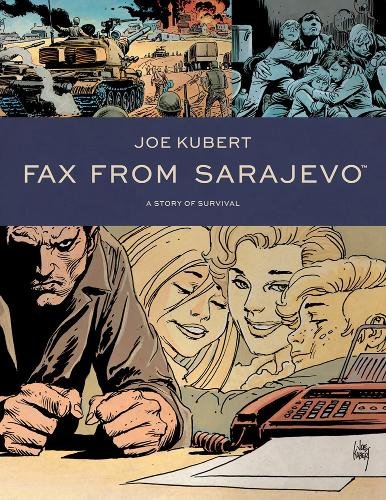

For those familiar with Kubert’s work from decades of war comics for DC it may be difficult to switch into his style applied to real world events, yet this is stunningly drawn from the heart. Rustemagic’s personal experiences are cut through with the revelations of others, most even more horrific, yet Kubert maintains a solidity in illustrating overwhelmingly distressing occurences, never descending into exaggerated melodrama. There are times when the shorthand Kubert required to compress so many events leads to some awkwardly expository dialogue, but weighed against the overall accomplishment this is a minor caveat.

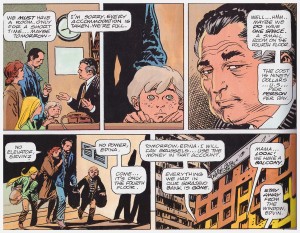

Rustemagic’s situation rapidly devolves from attempting to keep working under pressure, to protecting his family, home and belongings, to a desperate wandering existence. He continues to contact friends whenever possible, and they collaborate across the globe doing what they can to help him. A heartbreaking aspect of Fax from Sarajevo is the understated comparison between Rustemagic with friends overseas able to supply basic medicine, and hundreds of thousands of others without contacts. Yet there are always those willing to exploit people in need (see sample illustration).

It might be asked what the wider world was doing as atrocities continued, and the UN is touched upon in the earlier chapters, with Rustemagic aghast at their impotence. His faxes bookend story chapters, and the narrative is enhanced by a detailed afterword proffering greater detail and background information.

At the time of release Fax from Sarajevo was an acclaimed award winner, yet instead of becoming a standard title mentioned along with the greats of the genre it’s lapsed out of print, which is puzzling for something so excellent, vivid and emotionally compelling.