Review by Ian Keogh

When considering the life and work of Oscar Wilde it’s the wit of his epigrams, his tragic fate or The Picture of Dorian Gray that come most easily to mind. The more erudite might cite his plays or De Profundis, but the reputation of his fairy tales is strangely forlorn. It’s odd, as these are infinitely better than his overwrought poetry and far from the brief bout of sentimentalism during the youth of his children that they’re often dismissed as. Several sit comfortably alongside the best of the brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Andersen.

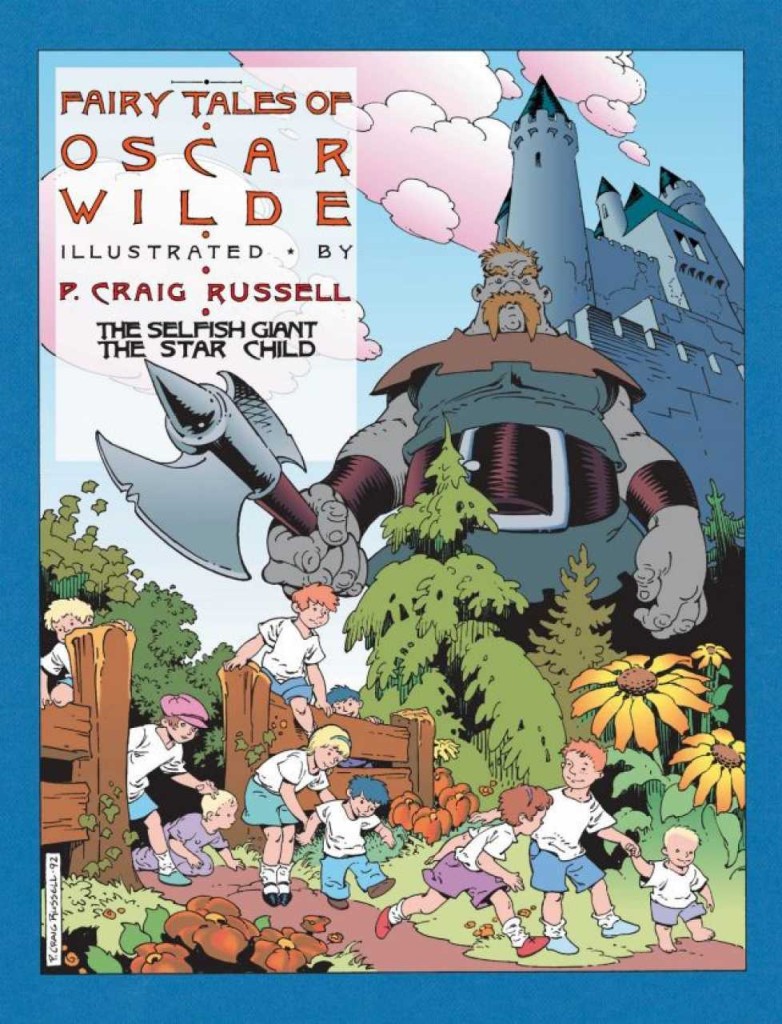

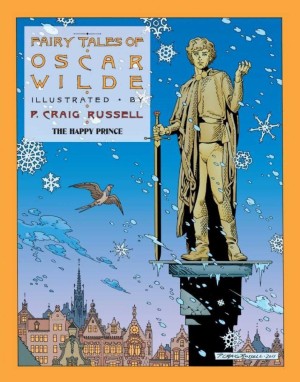

It’s The Selfish Giant that P. Craig Russell selects as his first adaptation of a Wilde fairy tale, and the subject of his cover. This is quite the artistic departure for Russell, evoking the children’s book illustrators of the 1920s and 1930s rather than Wilde’s earlier era, or Russell’s own ornate style.

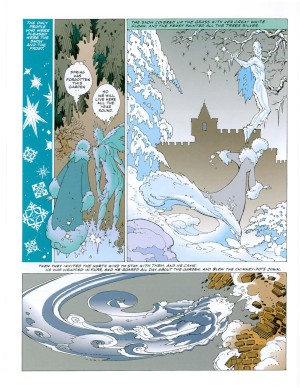

There’s plenty of that in evidence between the two hard covers. Given the delicacy of his usual work, it first comes as surprise that Russell’s at ease with the blundering awkwardness of the giant, but so it is. The illustrations are extraordinarily well composed. By way of a whimsical introduction Wilde accounted for the giant’s absence from his property by having him visit his cousin in Cornwall for seven years. After such a prolonged period their conversation has expired and the giant determines to return to his own castle. Wilde presents this as an upturned chair by the table and an open door. One can look through the book again and again and discover new layered and thoughtful touches. There are pages in both this and the following Star Child requiring a considerable amount of text to ensure a faithful adaptation, and on these Russell produces small accompanying illustrations so exquisite they distract from the blocks of text.

It’s the giant’s garden that becomes the subject for dispute. The neighbourhood children have become used to playing there while he’s been away and gathering the peaches that fall from the trees in summer, yet can do so no longer due to the vast wall the giant constructs. In true fairy tale fashion this selfishness has its consequences, but Wilde rapidly reverses them. By today’s standards the ending’s awkward fusion of fairy tale and religion is mawkish, but it hardly negates the joy of the remainder.

Those not familiar with The Star Child might wonder at points where the story’s going, but although not as well known as some of his other fairy tales, Wilde’s morality play comes from the heart, and its direction is allegorical. Adopted against advice as infant, a child found in the woods is loved and grows into a handsome boy, but one with an evil heart who persecutes others. His defining moment comes when he rejects his real mother on unreasonable grounds, and there his forced redemption begins. It’s a cruel story into which it’s not difficult to read Wilde’s own experiences, his secrets when he wrote it still largely unknown. That knowledge provides a poignant undertone to what’s good even at face value. The only puzzling aspect is the unduly cynical coda, perhaps another reflection of Wilde’s own worldview.

With their universal appeal it’s strange that there have been so few adaptations of fairy tales into graphic novels, but Russell sets the gold standard.