Review by Ian Keogh

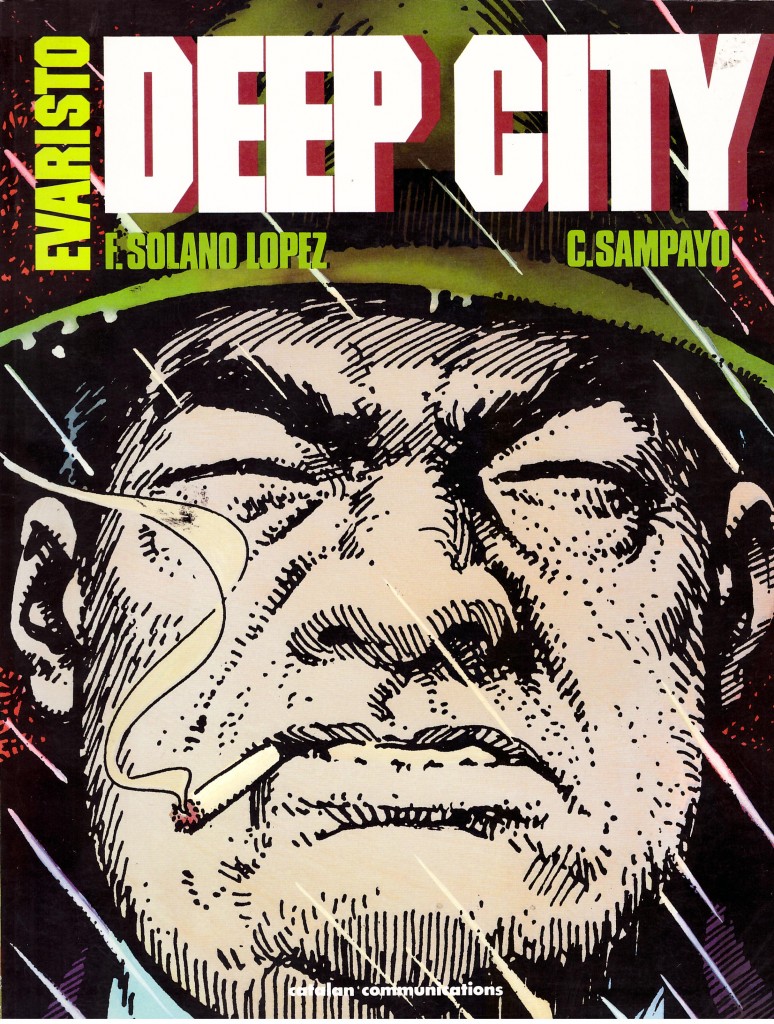

In his 1920s youth he was a boxing champion, but by the 1950s Evaristo is the city police commissioner in what’s presumably Buenos Aires. He’s a feared but pragmatic man, unwilling to forgo personal investigations, and one who’ll turn a blind eye for the greater good. Yet he’s also very much the product of his noir era, unconcerned about hitting women and believing other violence has a purpose. He transcends this with vision, chaining a murderer overnight in the porch of his victim’s family home before collecting him for prosecution the following morning.

The back cover blurb hopelessly undersells a very good collection of crime noir stories with what’s presumably poorly translated text waffling on about an obsession for describing how people are wounded by the passage of time. Carlos Sampayo’s memorable stories deal with the underclass in a country that when he wrote them was ruled by a brutal military dictatorship who protected vested interests, ensuring injustice was rife. He echoes this by reverting to an earlier time when life was cheap and the country ruled by a dictator. Evaristo is aware of which lines can be crossed, but Sampayo endows him with a great sense of justice. The times and his pragmatism ensure this stops short of moral crusades, but he’s principled. When an officer beats some children before delivering them to the police station, Evaristo ensures there’ll be no repeat performance.

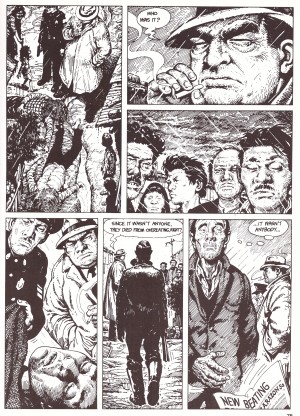

Both Evaristo and his environment are lovingly realised by Francisco Solano López. His bulky Evaristo is glorious creation, towering above almost everyone he meets, supremely confident and yet also an overweight man who sweats in the perpetual heat. Other cast members have an equal individuality, and they’re not idealised model specimens, but very ordinary looking. The city is lovingly reproduced and rich in background detail whether the homes of the wealthy, or more frequently the areas inhabited by the downtrodden. It’s not entirely characteristic, but one tale begins with a fantastic splash page portrayal of the conditions endured in a shanty town, the corrugated shacks at odd angles and buffeted by torrential rain.

All the political undertones never overwhelm a selection of good stories. Sampayo and Solano López damningly highlight a corrupt system, but the story comes first, and their penultimate collaboration is the best, lacking any political content. A lion on the loose in the city serves as a metaphor for Evaristo’s tenacious nature as he strolls around his territory all the while hearing updates on the radios he passes. A contract has been placed on his life, and he’s curious as to who’s responsible.

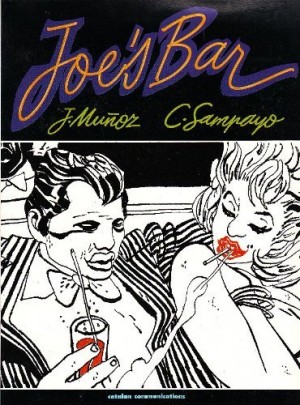

Sampayo’s storytelling partnership with José Muñoz would define his career, and this fine work is long forgotten and out of print, which is a great shame as it’s no way second rate. Evaristo is melancholy and conflicted, a superbly complex character deserving a far wider audience, and illustrated by another great artist. The only downside is a sometimes very poor literal translation that leaves sentences hanging and unanswered, but the quality seeps through anyway. Second hand copies of Deep City are easily located, and well worth your time.