Review by Frank Plowright

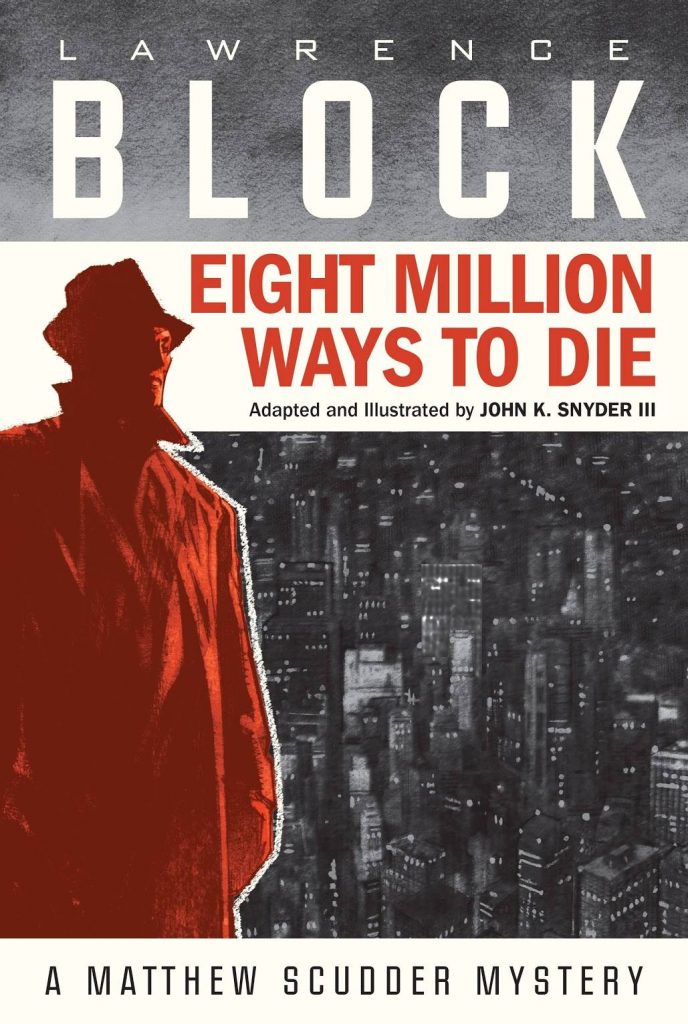

Quite a few graphic novels adapt crime stories, but very few have an introduction from the writer of the original novel. Lawrence Block’s name appears on the cover in a massive typeface, but the presence of his introduction counts for something, explaining the background, and noting he wasn’t a great fan of the first filmed version, but he loves John K. Snyder’s adaptation.

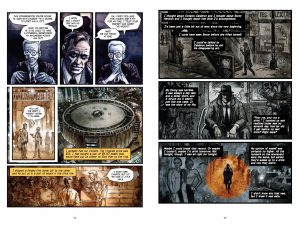

It’s easy to see why. Snyder packs in the entire story, recreates the sheer scuzziness of early 1980s New York, and gives every character the right nuances. Reluctant prostitute Kim Dakkinen retains her youthful glamour, curator of information Danny Boy Bell is dapper with an enigmatic air about him, and Matt Scudder, the man sucked into a bear pit, is suitably down at heel for an alcoholic former police officer. He’s not keen in labelling what he now does, but people know enough to approach him to solve their problems. What Snyder brings out very well via his art matching Block’s words is Scudder not being a happy man, unable to forgive himself for when a ricochet bullet he shot killed a child. His downbeat worldview is reinforced by the stories he’s told or reads, and passes on, such as one of a homeless guy stabbing another to death over a shirt found in a dustbin.

The surroundings, atmosphere and the personalities, especially Scudder’s, make the story as few of the events will provide any great surprise. Once attuned to Scudder’s worldview and mindset, the world conforms to it, and his constant struggle to avoid drinking overshadows much. Snyder ensures Block’s often pithy comments on the condition of humanity are passed on, and his is the anti-glamour side of detection. Scudder uses the contraction GOYAKOD, standing for “get off your ass and knock on doors”, and we see him living by his own advice, enduring the relentless monotony in the hope of turning something up. There is a second major character, but as they are one of the surprises, they’re best only mentioned in passing as interesting, and a great blow against stereotyping.

Some killer scenes break Scudder’s monotony, one being the mug attempting to rob him, and while Snyder’s generally true to the 1980s gutter atmosphere, he occasionally references a different life, such as the right sample art’s final panel. As with all crime stories, the perpetuating mystery concerns the killer’s identity, but in this case that’s really an irrelevance. Sure, there’s a revelation, but what makes Eight Million Ways to Die is the mood. It’s a cracking story to begin with, so Block provides the bullets, and Snyder draws the gun.