Review by Karl Verhoven

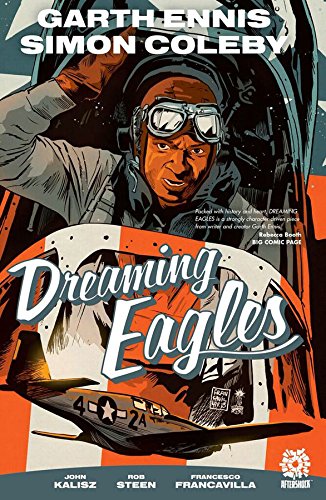

Francesco Francavilla’s cover depicting a World War II fighter pilot is a striking introduction to an educational distilling of the difficulties overcome by the men who became the first African American fighter pilots. Reggie Atkinson was a Tuskegee Airman who survived to pass on his experiences. Few Garth Ennis war stories are ordinary, but he takes an unusual approach in linking those struggles with those facing the subsequent generation, beginning with the social turmoil of the 1960s. A developing chasm between a father and son is due to neither being able to fully appreciate the other’s views on necessity.

A single graphic novel can’t go anywhere near to compensating for the loaded process African Americans had to overcome just to qualify as pilots in 1942, ridiculously for a nation that needed them, but it can lay them out to an audience that might not have previously realised. A blood-boiling succession of obstacles and untruths was dropped in their paths, and like Jackie Robinson forging his way through baseball’s post-war bigotry, a single natural violent reaction to abuse would undo the ultimate aim of proving the racists wrong. It’s a battle Reggie’s son is less inclined to follow through peacefully in the 1960s.

As is the case for other artists working on Ennis’ war stories, the expectation is that when it comes to the technical work Simon Coleby’s attention to detail is accurate and researched. Part of the narrative describes the design of a plane, and if checked back on other pages Coleby brings that to life. He’s better on the planes than people’s faces, which are sometimes a little vague and shadowy. Ennis supplies a considerable amount of technique, about flying escort missions safely among other priorities, and Coleby’s accompanying illustrations lay these out schematically, yet also with considerable verve. Despite representing horror and death, there’s a visceral thrill to be had from a good illustration of aerial combat, and there’s no shortage from Coleby.

Don’t just skim through Dreaming Eagles. Take time to read the captions, because they’re bloody good. Reggie describes how it feels to be sitting in the cockpit of a small plane taking a dive to avoid an attack as “gravity presses down and down on you, more than your body’s supposed to take. There’s a giant hand crushing you into the floor of the cockpit as if you’re nothing but clay…” Whether cribbed from an actual pilot’s experience or Ennis’ own description, how evocative is that?

There’s also a beautiful subversion of narrative expectation. Reggie’s wartime experiences are shared by his buddy Fats, actually a more instinctive pilot, and we all know what happens to the lead character’s best buddy in a war story. Ennis knows that as well as we do, and his avoidance of the usual is exceptional. If there’s a slight problem it’s that having opened Dreaming Eagles with the issues of the 1960s, they’re then sidelined, other than the acknowledgement of always being there.

Dreaming Eagles is rounded off with a four page essay from Ennis considering his research, the presentation of truth and his experiences flying in old warplanes. Anyone with good enough eyesight can also attempt to read the typed script for the first chapter, presented as three reduced pages to a book page. It’s remarkably precise and compact.