Review by Ian Keogh

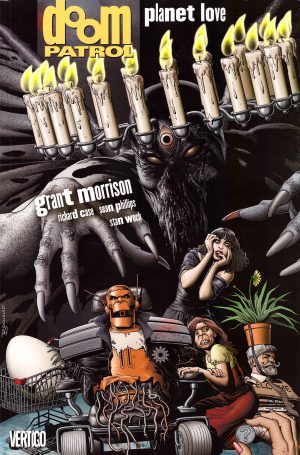

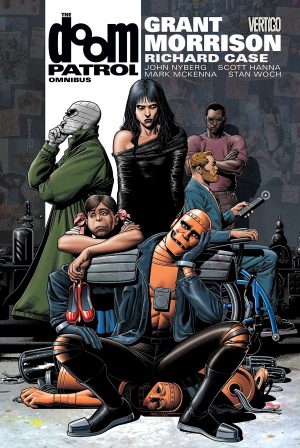

Grant Morrison began writing Doom Patrol in 1992, completing his run four years later. It may have been startlingly innovative and consistently entertaining, but just the single collection was issued while he was writing the series, the first half of this to be found as Crawling From the Wreckage. It may have prompted critical acclaim, but it wasn’t until 2004 that DC followed with the remainder of Book One in paperback, issued as The Painting That Ate Paris. It took until 2008 before DC finally ensured the entire series was again in print. More recently, however, they’ve belatedly recognised what they own the rights to. A hardcover Omnibus gathered Morrison’s entire run in 2014, and in 2016 this first of three bulky paperbacks was published. Better late than never.

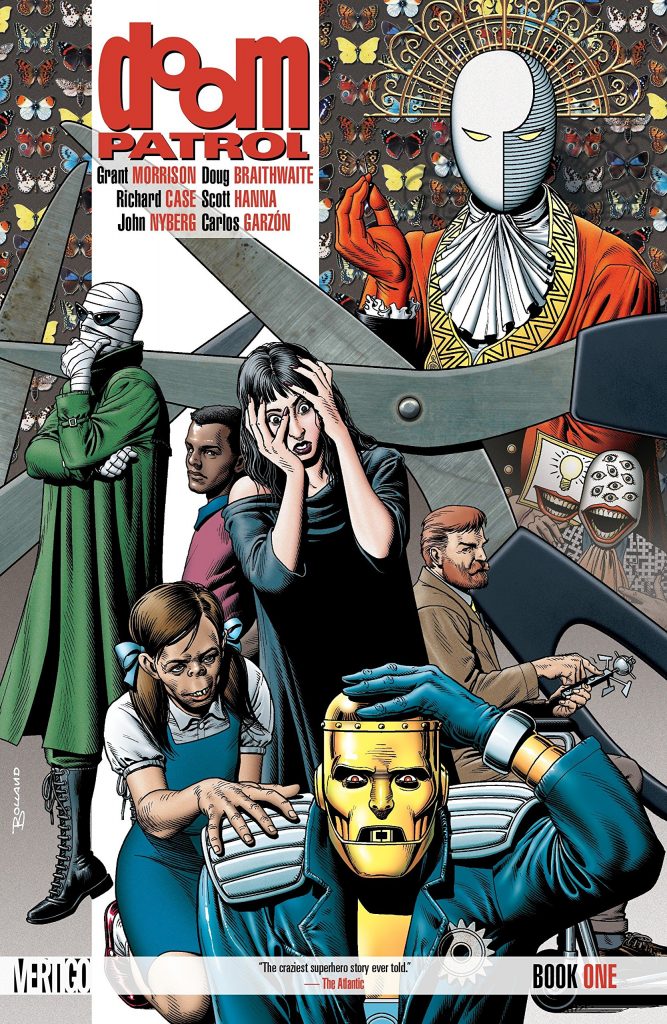

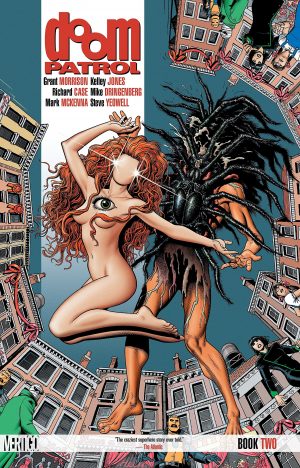

While there’s a lot to admire in the later books, this opening statement is the gold standard, Morrison setting off on a path of surreal absurdity, casually tossing off a positive waterfall of great ideas just as narrative caption window dressing. His interest in the existing Doom Patrol members extended no further than those from the 1960s incarnation, acerbic wheelchair bound genius Niles Caulder, Cliff Steele’s human brain controlling a technologically engineered robot body, and Negative Man. The bandaged Larry Steele could release a flying electrical persona for up to sixty seconds while his human body lay comatose. Morrison rechristened him Rebis and added a female persona to complete a trio. For fans of the other characters Morrison played fair, either sidelining them or relegating them to background roles until he could figure a purpose for them, which pays off magnificently with Rhea Jones in Book Two. He added his signature character, Crazy Jane, a fractured mind manifesting 64 distinct personalities, each with their own ability.

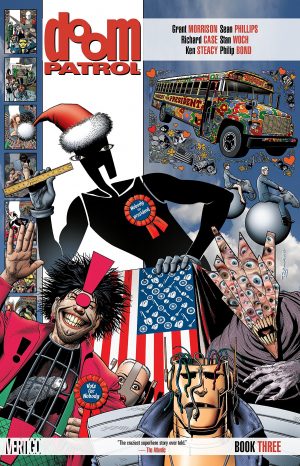

In the 1960s the Doom Patrol had always been strange and disturbing, and Morrison ramped that up extensively by pitting them against foes beyond normal comprehension, creatures that literally cut people from reality, an other worldly entity that was both God and Jack the Ripper in days gone by, and the Brotherhood of Dada, four lost souls with preposterous super powers. Morrison highlights the difference between how the Doom Patrol and other superheroes operate by having some members of the Justice League standing around wondering how the hell they’re going to retrieve Paris from within a painting. The Doom Patrol brush them aside and dive straight in.

This was a radical shift from superhero stories as they’d been to that point. While other writers had toyed with surrealism, no-one sustained the approach for so long, although Morrison himself would point to the twisted logic of 1950s DC material as a viable forerunner. It might have been a step too far had Morrison been paired with a similarly inventive artist, but he had Richard Case, almost doggedly determined to render the most outrageous creations in terms of standard superhero storytelling.

There are some misfires, the Withnail pastiche Willoughby Kipling outstaying his welcome, but this is mostly wildly inventive, still stimulating and often very funny. That’s more than enough.